If you’ve been following this series on the language(s) of Jesus, you know that I have argued that Jesus spoke Aramaic as his first language and in a substantial chunk of his teaching. I think it’s highly probable that he also spoke Hebrew, and used Hebrew in contexts when that was appropriate (reading the Scripture in the synagogue, conversing with Jewish scholars, etc.). I also believe that Jesus spoke Greek, though the evidence for his use of Greek is not as strong as it is for Aramaic (very strong) and Hebrew (strong).

But why does this matter? Does the question of Jesus’ language make any difference to us, especially to those of us who are followers of Jesus today?

Yes, I believe the language of Jesus does matter. I began this series by offering one reason. When we pay attention to the language of Jesus, we remember that he did not speak English. Therefore, we are encouraged to pay close attention to the meaning of his teaching in light of his cultural and religious milieu, and not to read Jesus as if he were speaking in 21st century America. I’ll say more about this in a moment.

I do not believe that the language spoken by Jesus makes any difference for our understanding of the authority of Scripture. I dealt with the argument that Scripture teaches that Jesus spoke only Hebrew, and therefore any claim that he spoke Aramaic or Greek undermines biblical authority. This argument is based on a misunderstanding of the biblical text. One can uphold the inerrancy of Scripture and believe that Jesus spoke Aramaic, Hebrew, and/or Greek. (Photo: A 4,000 seat theatre in Sepphoris, just modest walk from Nazareth. Jesus grew up not far from a major center of Greco-Roman culture. Used by permission of HolyLandPhotos.org)

The fact that Jesus may have spoken Greek may help us to think differently about him and his ministry. For many years it was common to envision Jesus as growing up in the countryside of Galilee, far removed from multi-cultural hodge-podge of the Roman Empire. But this idealized view of the rustic Jesus is far from the truth. Though he grew up in a small town, he was not at all cut off from the broader Roman world. In fact Jesus grew up with ample exposure to Greco-Roman language, culture, commerce, politics, religion, and philosophy. When he eventually entered Jerusalem to confront the Roman and Jewish authorities there – and to give his life in the process – Jesus was no naïve country bumpkin making his first trip to the big city. Rather he was well aware of powers and perils he faced, and he faced these knowing, as he ultimately said to Pontius Pilate (in Greek, I believe), “My kingdom is not from this world” (John 18:36).

The fact that Jesus may have spoken Greek may help us to think differently about him and his ministry. For many years it was common to envision Jesus as growing up in the countryside of Galilee, far removed from multi-cultural hodge-podge of the Roman Empire. But this idealized view of the rustic Jesus is far from the truth. Though he grew up in a small town, he was not at all cut off from the broader Roman world. In fact Jesus grew up with ample exposure to Greco-Roman language, culture, commerce, politics, religion, and philosophy. When he eventually entered Jerusalem to confront the Roman and Jewish authorities there – and to give his life in the process – Jesus was no naïve country bumpkin making his first trip to the big city. Rather he was well aware of powers and perils he faced, and he faced these knowing, as he ultimately said to Pontius Pilate (in Greek, I believe), “My kingdom is not from this world” (John 18:36).

Jesus’ use of the language of the kingdom of God (or heaven) provides a striking illustration of why it matters to know the language of Jesus. Let me explain.

Throughout the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus continually refers to the kingdom of heaven, as in “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Matt 3:2). Many Christians take the phrase “the kingdom of heaven” as a description of what we call heaven: the place where we go to be with the Lord after we die. This makes good sense in English, because “kingdom” signifies a place ruled by a king, and “heaven” is the place we believers go after we die, the place where God rules (Matt 6:10).

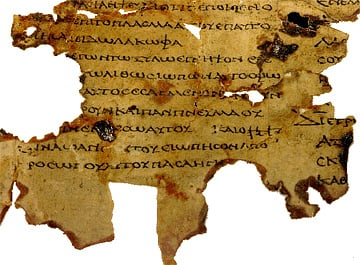

But this is not what Jesus meant when he used the Aramaic phrase malkuta dishmaya (which appears in the Greek of Matthew as he basileia ton ouranon). For one thing, the Aramaic word we translate as “kingdom” referred, not only to the place where a king rules, but to the authority of the king. Thus malku could be translated as “kingly authority, rule, or reign,” and should be translated this way in the case of Jesus’ usage. He’s not saying that the place where God rules in coming near, or that we can now enter that place, but rather that God’s royal authority is about to dawn, and is in fact dawning in Jesus’ own ministry. Moreover, the Aramaic term we translate as “heaven,” literally a plural form meaning “heavens,” was often used as a circumlocution for God, much as my grandmother used to say “Good heavens!” rather than “Good God!”

So when Jesus said “malkuta dishmaya has come near,” he didn’t mean that the kingdom of the “the place we go when we die” has come near, but rather that God’s kingly authority was at hand. Jesus proclaimed the reign of God and demonstrated its presence through doing mighty deeds, such as healings and exorcisms. By the way, everything I’ve just said about malkuta dishmaya in Aramaic would also be true if Jesus were speaking Hebrew and said malkuth hashamayim or Greek and said he basileia ton ouranon. For a right understanding of Jesus in this case, it doesn’t matter which ancient language he was speaking. But it does matter greatly that he wasn’t speaking contemporary English.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I’m not saying that there isn’t such a thing as a blessed afterlife or that Jesus has nothing to do with how we enter this afterlife. But I am saying that when we understand Jesus to be talking continually about what we call heaven when he speaks of “the kingdom of heaven” or “the kingdom of God,” we are fundamentally missing his point. He’s speaking, not so much about life after death, as about the experience of God’s kingly power in this life and on this earth, both now and in the age to come. (I have written extensively on the topic of Jesus’ teaching on the kingdom of God. See What Was the Message of Jesus?)

Given the excellent of English translations of the Bible by translators who have mastered all of the relevant languages, it’s not necessary for the ordinary Christian to learn Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic in order to understand the teaching of Jesus. (In my days teaching Greek in seminary, I did have a few students who were not planning to pursue ordained ministry, but simply wanted to be able to study the New Testament in greater depth!) I do think that any who are going to teach the Bible in a serious way, both clergy and lay, should gain deep familiarity with the primary biblical languages (Greek and Hebrew). But the good news is that we can understand and grapple with the teaching of Jesus without knowing the language or languages he actually spoke. You don’t need to speak any ancient language to hear Jesus’ proclamation of the reign of God or to be challenged by his invitation: “Follow me.”