In my last post in this series, I spoke of the centrality of forgiveness in peacemaking. While I’m speaking of forgiveness, I want to say a word about peacemaking in families. Everything I have said about peacemaking in church applies equally to family life. Humility, gentleness, patience, unity, and forgiveness belong at home. Unfortunately, home is often the toughest place to live out these virtues. When I come home from work, after a day of exercising humility, gentleness, patience, and forgiveness in my work life, I’m worn out. My children might get the last bit of peacemaking I can muster, though sometimes they don’t even get the dregs. My wife, Linda, however, can get pride, insensitivity, impatience, and unforgiveness. If she’s had a bad day too, you can imagine how much peace will bless our marriage that night.

As I grow in Christ, I’m learning to live my faith at home first and foremost, not last and least. But because I’m so human, as are my other family members, forgiveness pervades our household. Without forgiveness, we’d soon build up walls of hostility that would damage our fellowship and reflect poorly on the Lord. That’s the state of many families today, including many Christian families. Husbands and wives have substituted nice-making for genuine peacemaking, thus storing up bitterness against one another. The same is often true of other family relationships. Only forgiveness, forgiveness modeled after God’s own forgiveness and inspired by God’s own Sprit, will bring wholeness – shalom – to our families.

Sometimes, forgiveness is lacking because one who has wronged another is unwilling to admit the offense and ask for forgiveness. Now we can forgive even if someone will not own up to having wronged us. But it is much easier, emotionally, to forgive one who says, “Yes, I was wrong. I’m sorry. Please forgive me.”

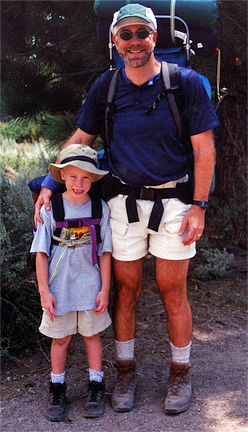

Parents can be especially resistant to admitting to their children when they make mistakes. I remember a time, years ago, when I was confronted with the question of whether or not to apologize to my son, Nathan. He had done something wrong, so I responded with a stern lecture and taking away some of his privileges. Yet, even as I finished with Nathan, I realized that I had been harsh and unfair. It occurred to me that I should apologize. But the thought of humbling myself before my young son and asking for forgiveness made me most uncomfortable. It would have been so much easier just to move on in the hope that we could forget the whole incident. Yet, as I thought and prayed about what to do, it seemed right to humble myself enough to apologize to Nathan and admit my error. How else would he learn how to admit his own mistakes? How else would he learn how to forgive? (Photo: Nathan and I, preparing for our first backpack trip.)

Parents can be especially resistant to admitting to their children when they make mistakes. I remember a time, years ago, when I was confronted with the question of whether or not to apologize to my son, Nathan. He had done something wrong, so I responded with a stern lecture and taking away some of his privileges. Yet, even as I finished with Nathan, I realized that I had been harsh and unfair. It occurred to me that I should apologize. But the thought of humbling myself before my young son and asking for forgiveness made me most uncomfortable. It would have been so much easier just to move on in the hope that we could forget the whole incident. Yet, as I thought and prayed about what to do, it seemed right to humble myself enough to apologize to Nathan and admit my error. How else would he learn how to admit his own mistakes? How else would he learn how to forgive? (Photo: Nathan and I, preparing for our first backpack trip.)

So I sat down with him, explained that I had been unfair, and asked for his forgiveness. I felt embarrassed and awkward. Nathan responded by saying, “Sure, Dad” and gave me a hug. I felt so much better! More importantly, I was beginning to teach Nathan how to be a person who admits his mistakes and who forgives others. I was being a peacemaker in my own family.

Throughout my years as a pastor, I have witnessed deeply moving examples of forgiveness in families. I’ve seen children forgive a father for his years of alcoholic abuse. I’ve seen husbands forgive wives who have been unfaithful in their marriage. And I’ve seen wives do the same. God’s grace enables us to forgive, genuinely and fully, what we could never do on our own.

But forgiveness is not pretending that everything is okay. If a husband is physically abusing his wife, for example, she does, in time, need to forgive him. But this doesn’t mean she should simply stick around and take the abuse. Forgiveness doesn’t turn us into human doormats, and it doesn’t take away the need for wrongdoers to confess and repent.

A Christian leader I know has a terrible temper. He has said and done things in anger that are clearly sinful. Yet, to my knowledge, he’s never truly confessed his sin to those he has wronged and asked them to forgive him. He seems to assume that his fellow Christians owe him forgiveness, which is true, of course. But it’s only half of the equation. The other half includes his willingness to admit his mistakes and seek forgiveness, not to mention to be held accountable for his behavior.

Peacemaking is not just something that happens “out there.” It begins in our closest relationships, in our homes and marriages, in our families and friendships.