The final Spirit to visit Ebenezer Scrooge is the “Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come” or simply the “Ghost of the Future.” This silent Spirit, shrouded in black, takes the mythic form of death. Not surprisingly, the visions it reveals to Scrooge also focus upon death and its meaning.

The largest portion of Stave 4, which is shorter than Staves 2 and 3, describes various reactions to the death of some unknown figure. At first, several men of business talk about this man’s death with curious indifference. Then Scrooge observes three people who robbed the dead man and are selling their booty in creepy part of town. Of course the reader guesses that the deceased victim is none other than Scrooge himself, but this doesn’t occur to Scrooge at this stage in the story, or, at any rate, he is unwilling to acknowledge what he senses. In fact, when he stands next to the covered body of the dead man, Scrooge is unable to lift the covering and discover whose body lies beneath it. He just can’t bring himself to face his own mortality.

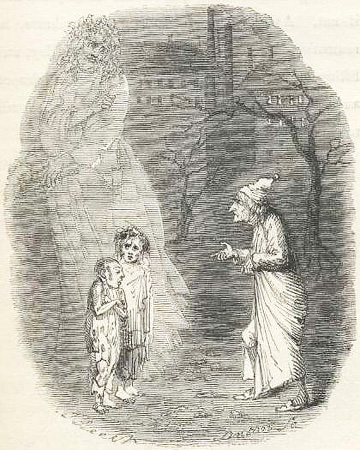

The most touching scene in Stave 4 involves the Cratchit family, minus Tiny Tim, who has just died. Their shared grief is almost tangible as they try nevertheless to enjoy a bit of Christmas cheer. Even so, Bob Cratchit breaks down with sadness, crying out “My little child!” Before Scrooge leaves the Cratchits, the family members resolve never to forget Tiny Tim, whom the narrator addresses: “Spirit of Tiny Tim, they childish essence was from God.” (Photo: “The Last of the Spirits.” Illustration by John Leech in the first edition of A Christmas Carol.)

In the final scene of this stave, Scrooge demands that the Spirit reveal the identity of the mysterious dead man. Soon Scrooge stands in a deserted graveyard, directed by the Spirit’s pointing finger to a neglected grave, the stone of which reads “Ebenezer Scrooge.” The horrified Scrooge realizes the sum total of his life, which amounts to zero (or less). He will die unloved and unnoticed, unless he chooses a different course of living from that moment on.

This is exactly what Scrooge resolves to do, even though the Spirit refuses to assure him that his life is redeemable: “Spirit!” he cried, tight clutching at its robe, “hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope? . . . I will honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

Yet the Spirit doesn’t speak, and, as Scrooge attempts to hold him, the Spirit turns into a bedpost, Scrooge’s own bedpost.

One might wonder why Dickens associates the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come with death. Michael Hearn, in The Annotated Christmas Carol, cites something Dickens wrote eight years after A Christmas Carol was first published:

“Of all days in the year, we will turn our faces towards that City upon Christmas Day, and from its silent hosts bring those we loved, among us. City of the Dead, in the blessed name wherein we are gathered together at this time, and in the Presence that is here among us according to the promise, we will receive, and not dismiss, they people who are dear to us!” (Hearn, p. 126)

Dickens seems to have experienced Christmas in the way many others do, as a time for remembering loved ones who have died. Therefore Christmas itself can lead to the remembrance of death. What appears to have altered Scrooge’s character, however, is not merely the fact of his mortality, but also the fact that his sad death accentuates the worthlessness of his life. The revelations of the Spirit make clear to Scrooge the emptiness of his life as seen from a post mortem perspective.

Theological Reflections

Death, it seems to me, does have a way of refocusing our vision, helping us see what matters most in life. I’ve frequently had this experience as I participate in memorial services, something I have done quite often as a pastor. Considering the death of someone else and the things said about that person after death cause me to examine the value of my own life. When my days on this earth have passed, will I have lived my life to the fullest? What will people say about me when my life has passed?

Moreover, confronting one’s own mortality can, indeed, lead to personal transformation. I think of people I’ve known who have had serious cancer, and who, in the aftermath, have decided to live with new priorities. Yet Christians believe that moving from death to life isn’t something we can will into existence, but requires the regenerating work of God. Indeed, we all need a Spirit, not a Christmas Spirit, but the Holy Spirit of God, to give us new life.

Finally, the theme of “death within Christmas” is also central to Christian theology. Though we celebrate the birth of Jesus at Christmas, we remember that his birth was a precursor to his death on the cross. It’s common to interpret the gift of myrrh as a symbolic foretaste of Christ’s death, since myrrh was used for embalming (see John 19:39). So, from a Christian point of view, the presence of death in A Christmas Carol makes sense.