“This morning I saw a Photoshopped image on Facebook that caught my attention,” writes self-described radical left-wing Christian activist Nichola Torbett in her blog Jesus Radicals.

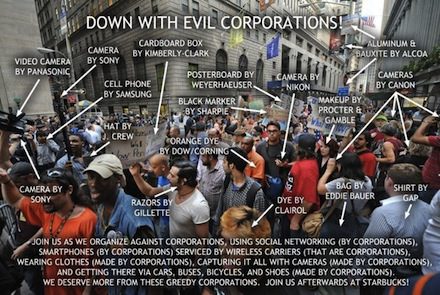

The photograph captured protesters at Occupy Wall Street, but superimposed over parts of the photo were captions like “Video camera by Panasonic,” “Camera by Sony,” “Black marker by Sharpie,” and “Posterboard by Weyerhauser.” Underneath the photo was a longer caption that ended with something like “Meet me at Starbucks after we finish protesting those greedy corporations.” As you might have guessed, the photo, originally posted by Midnight Trucking Radio Network and clearly intended to discredit the protests, was drawing the ire of my radical left-wing social network.

“So,” writes Torbett, “all this has me thinking that we need a confessing movement. We need a movement in which we start by confessing our part in the suffering we have perpetuated in our efforts to escape suffering ourselves. “Not my banker brother, not my stockbroker sister, but it’s me, O Lord, standing in the need of prayer.”

“So,” writes Torbett, “all this has me thinking that we need a confessing movement. We need a movement in which we start by confessing our part in the suffering we have perpetuated in our efforts to escape suffering ourselves. “Not my banker brother, not my stockbroker sister, but it’s me, O Lord, standing in the need of prayer.”

She continues:

Or maybe I should model this by starting with myself. I need a confessing movement. No matter how much I work for racial justice, my white skin and the (so far) continuation of white supremacy conspire to keep me locked in the oppressor position, keep me benefiting from the limitations placed on darker-skinned people. I do not think this nullifies my work for justice, but I do long for more honesty. I long for a place to say: “Sometimes I am greedy. Sometimes I put my personal profit above the good of the community. Sometimes I seek status at others’ expense. And I am not sure I can stop on my own.”

I long for a movement that transforms me as it transforms social structures. I can’t do any of that alone.

And so, I need you, and I need a confessing movement, so maybe it’s okay to say that we need a confessing movement. The confessing movement is a place for confession, yes, but it is also a place for radical repentance. It is a place to cry out to God for deliverance, a place to seek God’s face in each other and in the Spirit of change that seems to be gripping us, and a place to recommit to cultivating the disciplines of love, generosity, honesty, compassion, forgiveness, and gratitude.

The Confessing movement has been an evangelical movement within several Christian denominations striving to return those churches to the teachings of the Bible.

Its members have had a stated commitment to remain in their home denominations — which include evangelicals, Pentecostals, Holiness groups and such increasingly liberal mainstream churches as America’s Episcopal, Presbyterian, Disciples of Christ, Methodist, United Church of Christ (Congregational) and Lutheran churches, as well as fundamentalist groups, including the Southern Baptists, Mennonites, Christian Church/Churches of Christ and Bible churches. Participants have proclaimed they will stay within their denominations — unless forced out — to stay and work for reform from within.

Of particular concern to those in the Confessing movement has been a perceived lack of concern for, or non-evangelical approaches to, evangelism, to the deity of Christ and to the authority of the Bible. A large group of laity and a somewhat smaller group of clergy within the mainline churches have protested that their denominations have been “hijacked” by those who, in their view, have “forsaken Christianity” and embraced what they consider moral relativism.

Although many issues face the Confessing movement, the trigger that led to its formation has been whether the church can accept practicing homosexuals in leadership or condone same-sex marriage. Other issues have been the ordination of women and the decline in attendance of many of the historically mainline denominations while conservative congregations within their ranks were growing. Leaders of the Confessing movement claim the shrinking of membership as evidence of a wrong path taken.

But now from the ranks of “Occupy Wall Street,” Torbett calls for a Confessing movement “for ordinary people —

… imperfect and no less lovable for it, deformed by our experiences of social trauma, at once yearning and tentative — people of all colors, classes, abilities, genders, sexual orientations, immigration statuses, and ages, who are coming to understand that we have benefited (albeit to vastly different degrees, depending on our social locations) from the suffering of others.

We need a movement where it is safe to look honestly at ourselves, acknowledge our true histories, make mistakes, be forgiven, and keep moving forward together.

“So what do you think?” she concludes. “I’ll bring the ashes if you bring the sackcloth.”