The ruins of the 1,500-year-old St. Menas’ church and monastery near Alexandria, Egypt, are sinking into water-saturated soil and may be added to the UN’s list of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

The situation worsened two weeks ago with the collapse of an ancient crypt at the site.

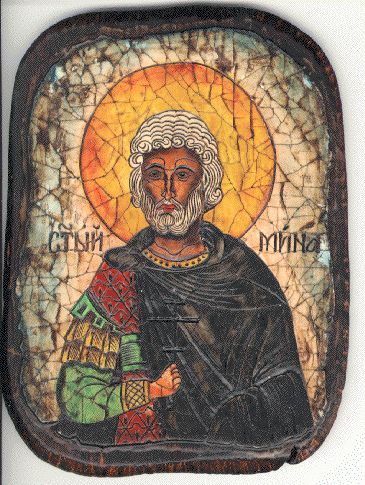

Called “Abu Mena” ever since it was destroyed around 600 AD during the Islamic Conquest, the church was built around 300 AD in honor of Egyptian martyr St. Menas. A monastery was added and the area became a Christian pilgrimage center. It was designated a World Heritage Site in 1979.

There are very few standing remains, but the foundations of most major buildings, such as the great basilica, are easily discernible.

The growth of agriculture in what was a desert area has led to a significant rise in the water table — which has caused a number of the site’s buildings to collapse or become unstable. Authorities have placed sand in the bases of several of the buildings that are most endangered.

St. Menas was martyred during the early Roman persecution of the church and, according to tradition, his body was taken from Alexandria on a camel, which was led into the desert. At the current ruins site, the camel refused to continue. This was taken as a divine sign and the martyr was buried there.

According to tradition, the location of the grave was lost until a miraculous rediscovery by a local shepherd. From the Ethiopian Synaxarium, translated by E.A.W. Budge:

And God wished to reveal the [place of the] body of Saint Mînâs. And there was in that desert a certain shepherd, and one day a sheep which was suffering from the disease of the scab went to that place, and dipped himself in the water of the little spring which was near the place, and he rolled about in it and was healed straightway. And when the shepherd saw this thing, and understood the miracle, he marvelled exceedingly and was astonished. And afterwards he used to take some of the dust from that shrine, and mix it with water, and rub it on the sheep, and if they were ill with the scab, they were straightway healed thereby. And this he used to do at all times, and he healed all the sick who came to him by this means.

Word of the healings spread rapidly. Roman Emperor Constantine is said to have sent his ailing daughter there. She is credited with finding Menas’ bones, after which Constantine ordered the construction of a church at the site.

By the late 4th century, the church and monastery were a significant pilgrimage destination for Christians who sought healing and other miracles. During the reign of the Emperor Arcadius, the local archbishop observed that crowds were overwhelming the small church. He wrote to the emperor, who ordered a major expansion of the facilities.

The site was first excavated from 1905 to 1907, uncovering a large basilica, an adjacent chapel which had probably housed the saint’s remains and Roman baths.

The site is in danger and needs major funds for restoration, says Mohamed Reda, head of Egypt’s Engineering and Technical Unit for the Museums and Monuments in Delta and Sinai at the Supreme Council of Antiquities.

The rise in groundwater levels is a common problem in the area.

The Supreme Council of Antiquities had allocated over 45 million Egyptian pounds — U.S. $7.5 million — to save the site using a network of water pumps and drainage systems and build a fence around Abu Mena to protect it from encroachments and theft.

Work at least 21 other archaeological sites have been put on hold due funding shortages, said explained Reda.

“Underground water has risen again by five meters and part of the Abu Mena crypt collapsed two weeks ago,” he said. Other endangered sites include a Jewish temple, the Greco-Roman Museum and the Mosaic Museum.