Is there an unwritten religious litmus test for the U.S. presidency? Do voters require candidates to be “not just religious, but acceptably religious”? Yes, say Northwest Nazarene University professors Steve Shaw and Darrin Grinder.

If they are right, will Mitt Romney’s Mormonism doom his bid for the presidency? After all, Catholicism was blamed for New York Gov. Al Smith’s loss to Herbert Hoover in 1928. Smith was denounced by vocal Southern Baptists and German Lutherans who were convinced he would take orders from the Vatican.

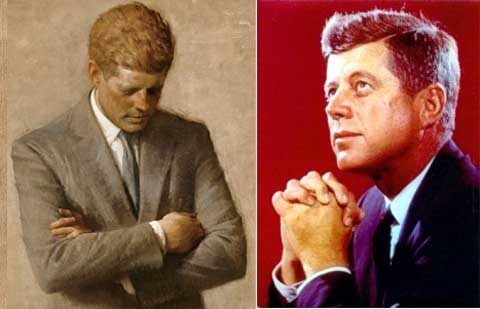

Such fears prompted John F. Kennedy to make a historic Sept. 12, 1960, speech to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He pledged he would resign if faced with a conflict between the Constitution and his beliefs.

It was speculated that Romney might make a similar declaration in his address to the late Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University commencement crowd on May 13, but he did not.

A “lingering suspicion among evangelicals — a key Republican constituency — about Romney’s Mormon faith,” writes David Gibson of the Religious News Service, “has led some to suggest that Romney needs to make a speech about his Mormonism along the lines of John F. Kennedy’s defense of his Catholicism to Protestant leaders during the 1960 campaign. So could Romney pull a Kennedy? Should he?”

Mike Huckabee, a Southern Baptist minister who sought the GOP nomination in 2008, told Fox News after Romney lost the 2011 South Carolina primary it was time for Romney to address his Mormonism – that such a speech would “sort of dismiss it, make it less important.”

But it’s not only the evangelical right that has questions. Sally Denton of the left-of-center magazine Salon cites “the White Horse prophesy” by Mormon founder Joseph Smith. He ran for president in 1844 as an independent commander-in-chief of an “army of God” advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government in favor of a Mormon-ruled theocracy. Challenging Democrat James Polk and Whig Henry Clay, Smith prophesied that if the U.S. Congress did not accede to his demands that “they shall be broken up as a government and God shall damn them.” Smith viewed capturing the presidency as part of the mission of the church and predicted the emergence of “the one Mighty and Strong” – a leader who would “set in order the house of God.”

Out of that, writes Denton, grew the “White Horse Prophecy,” which she describes as “a belief ingrained in Mormon culture and passed down through generations by church leaders.”

Former candidate for Nevada governor Michael Moody writes in his memoir that the prophecy “motivated me to seek a career in government and politics” because he felt he had been divinely directed to “expand our kingdom” and help Romney “lead the world into the Millennium.” Now a critic of the Mormon church, Moody says he was indoctrinated with the White Horse Prophecy.

“We were taught that America is the Promised Land,” he said in an interview.”The Mormons are the Chosen People. And the time is now for a Mormon leader to usher in the second coming of Christ and install the political Kingdom of God in Washington, D.C.”

Will such talk put off voters?

“Pundits and scholars, rabbis and bloggers, have repeatedly posed the question during Romney’s run: Is a candidate’s religion relevant?” writes Denton. “With a startling 50 percent increase of recently polled American voters claiming to know little or nothing about Mormonism, another 32 percent rejecting Mormonism as a Christian faith, a whopping 42 percent saying they would feel ‘somewhat or very uncomfortable’ with a Mormon president, and a widespread sense that the religion is a cult.”

“Pundits and scholars, rabbis and bloggers, have repeatedly posed the question during Romney’s run: Is a candidate’s religion relevant?” writes Denton. “With a startling 50 percent increase of recently polled American voters claiming to know little or nothing about Mormonism, another 32 percent rejecting Mormonism as a Christian faith, a whopping 42 percent saying they would feel ‘somewhat or very uncomfortable’ with a Mormon president, and a widespread sense that the religion is a cult.”

That could be a problem, write Shaw and Grinder. A politician’s religion is very important to voters.

Romney would not be the first president ever accused of belonging to a cult. Dwight D. Eisenhower was raised a Jehovah’s Witness and Richard Nixon a Quaker. Both, however, broke with their churches by joining the military. Eisenhower publicly became a Presbyterian.

“The U.S. Constitution forbids any religious test for political office,” notes Ohio’s Toledo Blade staffer David Yonke, reviewing Shaw and Grinder’s just-released book The Presidents & Their Faith: From George Washington to Barack Obama. “How the unwritten litmus test will play out in November is yet to be determined.”

Shaw told Yonke that in researching the writings, speeches and biographical information of America’s 43 presidents, each spoke to some extent of God, faith, providence, a supreme being, or a higher power. Shaw and Grinder had an easy job in documenting the unabashed of such presidents as Washington, Lincoln, Carter and Reagan. However, “there was a scarcity of information on some of ‘the forgotten presidents’ of the 19th century,” noted Yonke. Almost nothing is known about the faith of Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor or Franklin Pierce.

On the other hand, President James Garfield was a clergyman and Jimmy Carter taught a Sunday school class while in the White House.

“Lincoln is sort of a mystery,” says Shaw. “He never joined a church, he never uttered a profession of faith, he never claimed to be Christian, he would write or talk about wishing he were more devout, and he clearly read the Bible and knew religious language. He was a poorly educated man in official terms, but a highly read man and a deep theological thinker.”

Shaw said Lincoln’s second inaugural address on Mar. 4, 1865 — less a month before he was assassinated — was a magnificent meditation on divine will, in which he refused to claim that God favored either the Union or the Confederacy in the Civil War. “I find Lincoln almost impossible to figure out, and at the same time extraordinarily impressive,” he said. “He’s a moving figure to me, honestly.”

Some presidents’ faith was puzzling, write Shaw and Grinder – such as Andrew Jackson who professed his Christianity but described Native Americans as “inferior” and said they must “ere long disappear.”

President Harry S. Truman is not often thought of as religious, yet Shaw notes: “In his private diaries, he wrote a fair amount about religion and, just from my own perspective, wrote about being humble about one’s religious faith.” Truman wrote that when he walked from the White House across Lafayette Square to attend services at St. John’s Episcopal Church, he didn’t think anyone recognized him. Today, reporters follow a president’s every move – one of the reasons that the intensely religious Reagan cited for not attending any church while President.

Misunderstandings about Obama’s beliefs, noted Shaw, have not gone away even though he “has been very explicit about his faith, using precise religious language — not just talking about Almighty God or Supreme Being, but ‘Jesus Christ my Lord and Savior.’ He is a Christian as best we can measure that, and still 25 percent of the Republican base still doubts.” Indeed, polls show high numbers of Americans who believe he is a Muslim.

Clinton frequently quoted the Bible and spoke eloquently of his Christian beliefs, yet was “certainly the only president to be brought to trial over what were, essentially, attempts of a statesman to use his public power to cover his private sins.”

Shaw told Yorke he sees parallels between the controversy over Kennedy’s Catholicism and Romney’s Mormonism. “I think people today are surprised there was so much hostility toward John F. Kennedy in 1960. He got it from all quarters,” he said – JFK’s critics were not hesitant to display their prejudice against Catholics in ways that would be unacceptable today.

Shaw and Grinder quote Ted Sorenson, Kennedy’s speechwriter and special counsel, as saying, “The single biggest obstacle to his election was his religion.”

Will the problem be the same for Romney?