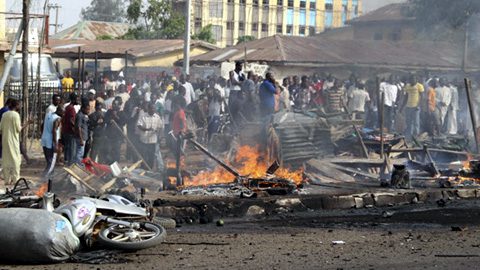

Just a few days ago, a car loaded with explosives attempted to get access to the First Evangelical Church Winning All in Kaduna, Nigeria. However, the suicide bomber’s car with a military uniform folded on the back seat was turned away at a barricade.

As he drove away, the massive bomb exploded outside a hotel opposite the church. At last count 39 people were dead, 125 wounded, many of them taxi drivers parked at the hotel. The massive explosion blew in the windows of the nearby All Nations Christian Assembly Church. But more than 200 children attending Sunday school at the targeted First Evangelical Church Winning All escaped injury – “by the grace of God,” church leaders told Nigeria’s Sun newspaper.

As he drove away, the massive bomb exploded outside a hotel opposite the church. At last count 39 people were dead, 125 wounded, many of them taxi drivers parked at the hotel. The massive explosion blew in the windows of the nearby All Nations Christian Assembly Church. But more than 200 children attending Sunday school at the targeted First Evangelical Church Winning All escaped injury – “by the grace of God,” church leaders told Nigeria’s Sun newspaper.

Moments later, another suicide bomber hit Christ the King Catholic Church building in nearby Zaria, killing another 12. A third attack struck the Shalom Church in Kaduna City, killing 10.

By the end of the week, 138 Nigerian Christians had been killed in subsequent attacks. Boko Haram, a Muslim terrorist group, took credit and bragged that more attacks would follow.

“In the past, every time they make threats they go ahead and do it,”said Jonathan Racho of the advocacy group International Christian Concern, “so we have every reason to believe that this is not a rhetorical statement – and we urge the Nigerian government to take this very seriously and take action.”

Boko Haram has been responsible for more than 620 Nigerian deaths this year alone, according to the Associated Press, targeting churches, state offices, law enforcement sites and even moderate Muslim mosques in its effort to destabilize Nigeria’s government. The professed goal is to see Shari’ah (Islamic law) on the entire country, which is 49 percent Muslim – mostly in the north – and 51 percent Christian, primarily in the oil-rich south. Nigeria is Africa’s most populous nation and its largest petroleum producer.

In another such oil state, Iran, Muslims make up the majority and members of the Baha’i faith are in the minority – although their faith was founded in Iran.

“Imagine being unable to attend college or hold a job simply because the government does not approve of your religion,” writes Sue Chehrenegar for the website GroundReport. “That is the obstacle that faces every member of Iran’s Baha’i community. The government has been persecuting the Baha’is for more than 30 years.”

Chehrenegar cites a number of Iranian persecutions of Baha’i, including the hanging of “a group of women in the City of Shiraz. Their crime had involved carrying out an act that a number of American men and women perform each week, while teaching Sunday school classes. However, those women had not been teaching about Jesus or Mohammed. Each of their lessons had sought to offer a few details about the life and teachings of Baha’u’llah, the prophet founder of the Baha’i faith.”

In the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, a frequent target of Islamist terror are the Ahmadis, a religious sect which claims to be Islamic, but which is rejected as heretical by Muslim fundamentalists. Qasim Rashid for the Huffington Post describes a recent attack on an Ahmadi mosque: “Out of the silent night, two men moved swiftly through the mosque’s front gate. Magazines loaded and safeties off, one stopped at the front door, the other proceeded through. All that separated a fully loaded Kalashnikov in the hands of a madman from 50 innocent worshippers was a straw curtain that hung helplessly in the doorway.”

Opening fire, the gunmen killed eight and injured 20. Rashid tells how after the massacre, “I listened silently as Yusef related the events in his hometown of Mong, Pakistan. The 50 innocent worshipers were Ahmadi Muslims. In Pakistan, Ahmadi Muslims are nothing more than ‘the Wrong Kind of Muslims,’ and therefore declared worthy of death.”

And trouble is brewing on the former India-Burma frontier. “Running north to south along the Myanmar-Bangladesh border, a forgotten ethnic minority group of the modern world – the Rohingya – are dying by the thousands,” reads a call to action printed worldwide in such newspapers as the Malaysia Sun Daily and on websites across the globe in the last week.

“According to witnesses, hundreds have been turned away by authorities in neighboring Bangladesh after attempting to flee the fighting in Myanmar,” writes Azril Mohd Amin, the vice president of the Muslim Lawyers Association of Malaysia. “The Rohingya are Muslims and have never been granted citizenship or any other right by the Buddhist Myanmars, who don’t want them and have always tried to force them over to Bangladesh.”

What follows is a justification for armed action against Myanmar’s Buddhists that is far too reminiscent of Hitler’s reasons for invading Poland and Czechoslovakia, sparking World War II. He was “protecting” German-speakers in both countries.

Amin acknowledges that what is going on in Myanmar is part of a worldwide phenomenon – the persistent, violent confrontation of Islam against its non-Muslim neighbors: “Aside from the spiritual clash which marks so many other ‘bloody’ borders (as Samuel Huntington calls them), there seems to be no possible reconciliation between the monotheists and polytheists of the world. The polytheists hold the money while the monotheists suffer untold miseries arising from lack of economic as well as educational equity.”

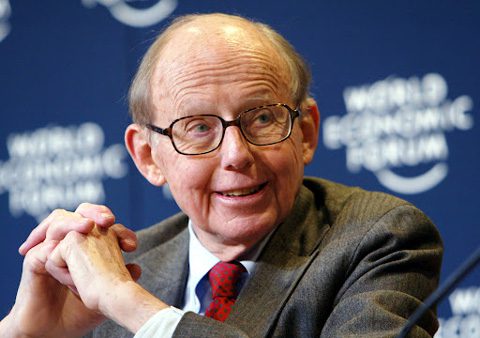

“Bloody borders” was coined by the late Huntington in a 1993 article “The Clash of Civilizations?” in Foreigns Affairs magazine. He elaborated in his book The Clash of Civilizations and The Remaking of World Order. Here’s a quote from the article:

“The interactions between civilizations vary greatly in the extent to which they are likely to be characterized by violence. Economic competition clearly predominates between the American and European subcivilizations of the West and between both of them and Japan. On the Eurasian continent, however, the proliferation of ethnic conflict, epitomized at the extreme in ‘ethnic cleansing,’ has not been totally random. It has been most frequent and most violent between groups belonging to different civilizations. In Eurasia the great historic fault lines between civilizations are once more aflame.

“This is particularly true along the boundaries of the crescent-shaped Islamic bloc of nations from the bulge of Africa to central Asia. Violence also occurs between Muslims, on the one hand, and Orthodox Serbs in the Balkans, Jews in Israel, Hindus in India, Buddhists in Burma and Catholics in the Philippines. Islam has bloody borders.”

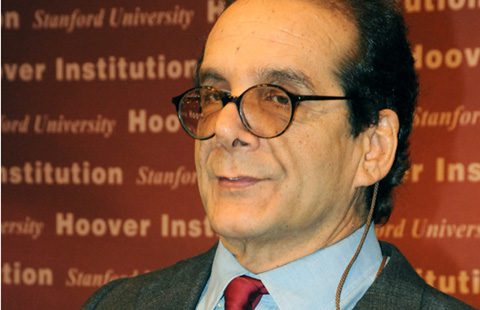

Is such an indictment of Islam unfair? Not at all, writes Charles Krauthammer: “Is Islam an inherently violent religion? And there is no denying the fact, stated most boldly by Samuel Huntington, author of The Clash of Civilizations? From Nigeria to Sudan to Pakistan to Indonesia to the Philippines, some of the worst, most hate-driven violence in the world today is perpetrated by Muslims and in the name of Islam.

“In Pakistan, Muslim extremists have attacked Christian churches, killing every parishioner they could. Just last month in Lebanon, an evangelical Christian nurse, who had devoted her life to caring for the sick, was shot three times through the head, presumably, for ‘proselytizing.’

“On the northern tier of the Islamic world, even more blood flows – in Pakistani-Kashmiri terrorism against Hindu India, Chechen terrorism in Russian-Orthodox Moscow and Palestinian terrorism against the Jews. (The Albanian Muslim campaign against Orthodox Macedonia is now on hold.) And then of course there was Sept. 11 – Islamic terrorism reaching far beyond its borders to strike at the heart of the satanic ‘Crusaders.’”

Recently, the secular humanist magazine Free Inquiry, attempted to tar all people of faith with the same brush in an article “The Intimate Dance of Religion and Nationalism.” But just as all African-Americans do not have rhythm and all Chinese students are not Einsteins, all people of faith are not murderers. Furthermore, as Huntington points out in the 199os, nationalism faded decades ago as the issue confronting today’s world peace.

Nowhere is this seen more vividly than in Sudan, a nation as ancient as Egypt. There, a 40-year conflict has not been fed by any nationalistic fervor to expand Sudan’s borders nor any nationalistic call to “liberate” or “restore to the motherland” those ethnic Sudanese living in neighboring Ethiopia or Uganda.

Instead Sudan’s conflict has been a vicious ethnic cleansing in which the Muslim north, populated by white Arabs, has attempted for decades to eliminate the southern blacks, who have lived there since the dawn of time – long before the Arab invasion that began in the 7th Century. The Arabs’ determination to grab the south’s rich oilfields has spawned some of the most horrific genocide in the history of mankind, particularly in the Darfur region – prompting unprecedented United Nations intervention.

“UN Secretary General Kofi Annan was plunged into the chaos of war-torn Darfur on Saturday when he was greeted in a western Sudan refugee camp by accounts of rape and murder and civilians venting their anger,” reports a 2005 article in the Pakistan Daily Times.

Stories coming out of Darfur strain the imagination – such as the “Lost Boys of Sudan,” many as young as five, who escaped attacks on their villages since they were playing in the bush or herding goats – but who watched in horror as gangs in helicopters and jeeps raided their villages, hacking their fathers to death with machetes, then raping their mothers and sisters before dragging them off to be sold in slave markets. Thousands of the boys began showing up at refugee camps in Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda, some walking more than 1,000 miles across the desert – blurting out nightmarish stories. Some told of being forced to serve as child soldiers – pumped full of drugs and turned loose with automatic weapons on rival tribes, told to take vengeance on the enemies who had killed their families and destroyed their villages.

Others had been sold and treated worse than cattle. One ten-year-old ex-slave told of refusing to recant his Christian faith and being crucified – nailed to a wooden cross – by his Muslim owner, then rescued by a kindly Muslim neighbor who helped him escape in the night to a refugee camp, where starvation was rampant and survival difficult.

“Seven women pooled money to rent a donkey and cart, then ventured out of the refugee camp to gather firewood, hoping to sell it for cash to feed their families,” reported Alfred de Montesquiou for the Associated Press in a 2007 article. “Instead, they say, in a wooded area just a few hours walk away, they were gang-raped, beaten and robbed. Naked and devastated, they fled back to Kalma.

“Seven women pooled money to rent a donkey and cart, then ventured out of the refugee camp to gather firewood, hoping to sell it for cash to feed their families,” reported Alfred de Montesquiou for the Associated Press in a 2007 article. “Instead, they say, in a wooded area just a few hours walk away, they were gang-raped, beaten and robbed. Naked and devastated, they fled back to Kalma.

“‘All the time it lasted, I kept thinking: They’re killing my baby, they’re killing my baby,’ wailed Aisha, who was seven months pregnant at the time. The women have no doubt who attacked them. They say the men’s camels and their uniforms marked them as Janjaweed – the Arab militiamen accused of terrorizing the mostly black African villagers of Sudan’s Darfur region.

“Their story, told to an Associated Press reporter and confirmed by other women and aid workers in the camp, provides a glimpse into the hell that Darfur has become as the Arab-dominated government battles a rebellion stoked by a history of discrimination and neglect.”

The Janjaweed militias ran rampant over south Sudan, financed by the Muslim north, assigned a single task – to devastate the south into submission.

“Deliberate attempts to eliminate a viable Christian presence are extreme and include bombing of Sunday church services; destruction of churches, hospitals, schools, mission bases and Christian villages; massacres and mutilation; and murder of pastors and leaders,” reported the Canadian watchdog group Voice of the Martyrs. “Whole areas have been laid waste and lands seized and given to northerners.”

After confirming 2 million deaths and 4 million refugees, the UN oversaw January 2011 elections in which the non-Muslim south voted overwhelmingly for independence from the Muslim north. The country was partitioned on July 9, 2011 but violence continues – primarily in two oil-rich provinces in which the north blocked any independence voting. The United Nations reports hundreds have died and 94,000 displaced due to the violence.

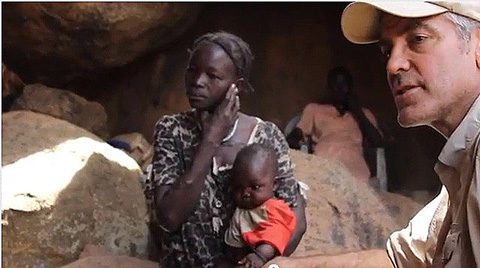

On March 16, actor George Clooney earned international headlines when he and nine other activists protested outside of the Sudanese Embassy in Washington, D.C., drawing international attention to the unfolding humanitarian crisis in the troubled border region between Sudan and South Sudan.

“Protesters who had gathered to take part in the National Day of Action for Sudan rally cheered Clooney as police fastened flexicuffs around his wrists and drove him off for processing,” reported Lucy Chumbley. “Later that afternoon, after posting and forfeiting a $100 bond, Clooney was free to go home. But for Episcopal Church of Sudan Bishop Andudu Adam Elnail, who also spoke at the rally, there will be no such homecoming.

“Elnail, leader of the Diocese of Kadugli in South Kordofan, Sudan, has been in exile since last June, when Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir’s Sudan Armed Forces attacked Kadugli, looting churches, routing priests and burning All Saints Cathedral, the diocesan offices and guesthouse and Elnail’s own house to the ground.

“In April, Elnail plans to travel to Yida, a camp across the border in South Sudan where many from his diocese have taken refuge. There, he said in an interview following the rally, he hopes to help clergy set in place new strategies for helping people in times of war, ‘encouraging them, raising their morale and encouraging them to stick to the Bible.’”

He warned of a famine this year, since the Sudan government’s attacks displaced tens of thousands just at the start of the planting season.

“There is hunger coming now and already people are hungry,” he said.

“Once you don’t plant anything, there’s nothing you’re going to harvest,” said Jimmy Mulla, president and co-founder of Voices for Sudan, a U.S.-based coalition of Sudanese-led organizations.

The famine is particularly acute in the two provinces the north has not allowed to vote – the border areas of South Kordofan and Blue Nile. There the government is again attempting ethnic cleansing, said Mulla.

Last June, just ahead of South Sudan’s independence, the Sudan Armed Forces began bombing the border regions and is now refusing to allow aid into these areas.

Al-Bashir has “decided since he can’t win militarily, he’s going to starve everyone to death,” says Andrew S. Natsios, author of Sudan, South Sudan and Darfur: What Everyone Needs to Know, published by Oxford University Press.

So, is all religion in general to blame?

Some academics are quick to embrace that thesis, but not historian Augustine Perumalil. In a 2004 paper, he examined what he calls “two views of religion-inspired violence which are popular in certain circles – the view that it is in the very nature of religion to generate violence; and that the cause of religious violence is the presence of male pronouns and violent images in religious discourse.”

He found both “inadequate,” instead coming to the conclusion that “much of the violence attributed to religion is in fact caused by deeper social, economic and political conflicts arising from the avarice of certain sections of society for dominion, and from a sense (actual or imaginary) of deprivation, injury, injustice and insecurity of the masses.”

He noted that “People are sanctioned to kill in defense of country and defense of religion. For some entities, the fight is no longer my form of government against yours. It is my religion and my beliefs against yours.” But, as Hungtington observed and as Mark Juergensmeyer noted in his 2001 book Terror in the Mind of God, since the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, there has been a sharp increase in the religion-related conflicts.

“With the fall of the USSR,” writes Perumalil, “fighting in the name of religion has replaced the battles pitting the capitalist West against the Communist bloc.”

William Edelen, in a 1999 article “Religion is the Cause of Violence,” places the responsibility for violence solely at the door of religion and argues that it is religion’s very nature to provoke conflict. In fact, he charged, religion has been the culprit from Moses to the Crusades, Henry VIII, Salem, Hitler and Kosovo.”

Such an argument is “flawed on account of being simplistic,” observes Perumalil. What is truly to blame — religion – or the inherent darkness of human hearts – which religions from the dawn of time have attempted to address?

Consider Jesus Christ and the Apostle Peter in the Garden of Gethsemane. The Gospel of John, chapter 18, tells us that at the conclusion of the Last Supper, Jesus went out into the night with His disciples. Judas, who had accepted 30 pieces of silver to betray Him, knew the garden where Jesus liked to pray and guided the soldiers there, carrying lanterns and torches and weapons.

Jesus, knowing what was about to befall Him, said, “Whom are you seeking?”

They answered, “Jesus the Nazarene.”

Jesus answered, “I am He.” As they stepped forward to arrest him, Peter drew a sword and struck Malchus, the high priest’s servant, severing his right ear.

What followed was not a historic battle between good and evil forces. Instead, Jesus said to Peter, “Put the sword back into the sheath! The cup which My Father has given Me, shall I not drink it?” Then He picked up the ear off the ground and healed Malchus.

As we see far too often today, the divine did not prevail over human will that night. The disciples became confused that Jesus was intent on living out His instructions to them that if someone should strike them on one cheek, they were to turn the other one also.

We humans just don’t get this “turning the other cheek” idea. It’s too dangerous. It requires trusting in the Almighty. We aren’t very good at that.

Even though Jesus performed an incredible healing miracle – restoring his wounded enemy to full health, the darkness of the human heart prevailed. Jesus was arrested, paraded through the city, given a mock trial, then executed alongside two petty criminals. The disciples would have preferred to launch a religious war right then and there. Only days before, the people of Jerusalem had lined the streets, laying down their coats and palm branches in front of their Messiah, mistakenly believing He was about to lead them in a triumphant rebellion against the occupying Roman Empire – and would re-establish the mighty Israel once led by King David.

Instead, Jesus allowed Himself to be crucified – and in doing so established a kingdom that the human mind still has trouble grasping, a realm which would transform Western Civilization and alter the course of world history.

Seven centuries later, some would say Christianity was saved when French military genius Charles Martel turned back the Muslim invasion that had conquered the Holy Land and swept over predominantly Christian Turkey and Egypt – imposing Islam from the Balkans to India and deep into Africa.

In October of 732, at the Battle of Tours, Martel stopped the Islamic hordes from sweeping over Europe.

Historian Edward Creasy said Martel’s decisive victory “gave a decisive check to the career of Arab conquest in Western Europe,” and birthed modern civilization. Historian Edward Gibbon is clear in his belief that the Muslim armies would have conquered the known world — from Japan to the English Channel — had Martel not prevailed.

“Few battles are remembered 1,000 years after they are fought, but the Battle of Poitiers, (Tours) is an exception,” wrote Matthew Bennett, a co-author of the 2005 book Fighting Techniques of the Medieval World.

Dexter B. Wakefield writes in An Islamic Europe: “A Muslim France? Historically, it nearly happened. But as a result of Martel’s fierce opposition, which ended Muslim advances and set the stage for centuries of war thereafter, Islam moved no farther into Europe. European schoolchildren learn about the Battle of Tours in much the same way that American students learn about Valley Forge and Gettysburg.”

William E. Watson wrote in 1993: “One can even say with a degree of certainty that the subsequent history of the West would have proceeded along vastly different currents had Abd ar-Rahman been victorious at Tours-Poitiers in 732.”

And here’s an irony: Given the example of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, Martel’s taking up arms contradicted everything that Christianity stands for.

Indeed, it set the stage for years of conflict and armed struggle — ignoring Jesus’ strong rebuke of Peter, telling him to put away his sword and, instead, to trust in God to provide a better way.