Waving her diploma over her head, Guadelupe Rojas walked across the stage, shook various university officials’ hands, and laughing took a bow as her family and friends in the bleachers cheered, whistled and applauded.

Her brother, Kiko, who will earn his teaching degree next year, blew a horn that noisily played the first notes of “La Cucaracha.” “Go, Lupe!” yelled her high school history teacher, a retired judge who had recognized her potential when she was a ninth grader – and tried to get her to pursue law as a career. Her grade school’s cafeteria manager stood on a chair, applauding loudly. Her longtime soccer coach blew a referee’s whistle and whooped. His wife blasted a boat air horn.

At the microphone, a dean in cap, gown and academic sashes smiled. “Congratulations, Lupe,” he said. “Best of luck.”

He knew all too well that the young Mexican native will need it. Although Guadelupe graduated from the Honors Program with honors and a double major in physics and math, she faces a grim future. The job market is dismal enough for ordinary college grads; it’s far, far worse for kids here illegally.

Lupe was born near Reynosa, Mexico.

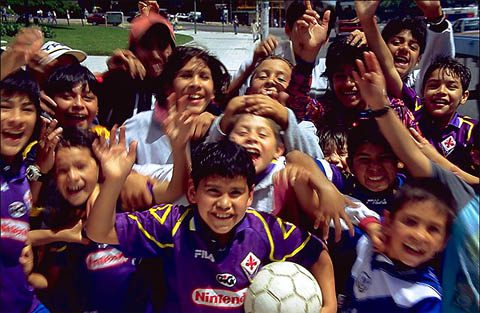

Arriving in America as a six-year-old, she showed up at a youth soccer practice where her coach asked where she was from.

“Mexico,” the first grader told him in amazingly good English. “But we live here now. My Mommy and Daddy had to wait until nighttime and they waded across the river. But my uncle and my aunt have papers, so they met us at Burger King in Matamoros and drove me and Kiko across. We pretended to be asleep. When the border guards tried to wake us up, we acted like we were sleepy. In English, I kept saying, ‘Are we there yet? Are we there yet?’ like I was dreaming. We fooled him!”

Solemnly, her coach listened. “Lupe,” he said quietly. “That is a great story. Now, you have to promise me that you will never tell it to another Anglo. That story has to be a secret. Do you understand me?”

Soberly, she nodded, her eyes enormous. She never told the story again – to anybody. By the time she was a fifth grader, she and the coach’s daughter, also a fifth grader, were assistant coaches for the local soccer league’s kindergartners. As seventh graders, the two became referees. In eighth grade, Lupe started coaching her own team of third graders.

Although she was a starter on the high school varsity girls’ soccer squad, she earned a full scholarship because of her grades, her SAT and ACT scores, her class standing and her years of community service. She had a 4.3 grade point average – the extra .3 Continued on Page 2