Do Americans have less faith in God?

Or is their crisis of faith in the professional bureaucracies claiming to represent Him — particularly in the old, historic “mainline” denominations — the Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Disciples of Christ, Methodists and what remains of the Congregationalists?

The New York Times’ Ross Douthat a few days ago observed that the Episcopalians’ and Presbyterians’ recent conventions didn’t “seem to be offering anything you can’t already get from a purely secular liberalism.” In other words, why bother going to such a church when you can get more at the Rotary Club or your favorite sports bar? The same week, Gallup released a new poll showing that Americans have decreasing faith in organized religion as an institution.

However, their disinterest isn’t in the Almighty. Gallup consistently shows that an overwhelming majority – more than three-fourths – of Americans say they are Christians.

Worldwide, church membership is up – and growing. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Center for Global Christianity reports that there are 1.1 billion Roman Catholics – and in the next 12 years, the number will increase 15.5 percent to 1.3 billion. In the same period, traditional mainline Protestants are expected to grow by 11.22 percent – from 346 million to 385 million.

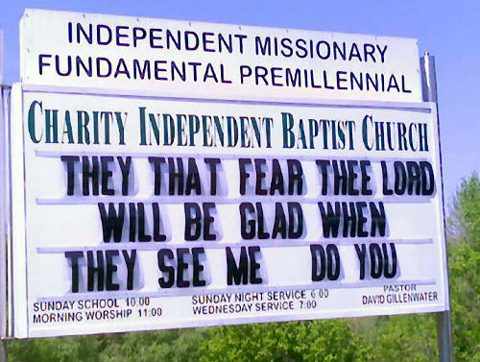

However, another unsung group of Christians is eclipsing the traditional mainline Protestants. Evangelical independents are projected to grow 15.8 percent by 2025 to 437 million – 50 million more than the traditional mainstream Protestants. These are churches that don’t answer to any central hierarchy.

Reporting the numbers of these generally conservative and Bible-based Christians is tough since independents don’t turn their numbers in to any central headquarters.

Such independents have already outstripped the traditional mainline Protestants, according to Gordon-Conwell, which estimated their numbers at 377 million. But it’s not easy for religion writers to report on this nonconforming group. And so in the last week, the old mainline churches continued to get the big headlines – debating cross-dressing clergy, same-sex marriage and other liberal causes such as supporting the Palestinians over the Israelis.

But, how relevant are they? Do their announcements and pronouncements mean anything to anybody outside of their ever-shrinking circles? Why are they even newsworthy these days? After all, more kids play baseball than the entire membership of the Episcopal Church U.S.A. There are 10 times more stamp collectors in America than Congregationalists.

The old mainline churches have been in sharp decline for the last 50 years, according to the National Council of Churches Yearbook. Membership of America’s “big five” mainline Protestant denominations, the Episcopal, United Methodist, Presbyterian (USA) and Christian (Disciples of Christ), all combined – has shrunk until their numbers together are smaller than the Southern Baptists.

The Southern Baptist Convention reports 16.2 million members. Again, it is difficult to report actual Baptist numbers due to all the unaffiliated and independent Baptists that dot the countryside — Alliance Baptists, American Baptists, Bible Baptists, Conservative Baptists, Continental Baptists, Evangelical Free Baptists, Free Will Baptists, Full Gospel Baptists, Fundamental Baptists, General Baptists, Indian Baptists, Landmark Baptists, Missionary Baptists, National Baptists, Primitive Baptists, Reformed Baptists, Regular Baptists, Old Regular Baptists, Seventh Day Baptists, Six-Principle Baptists, Two-Seed-in-the-Spirit Predestinarian Baptists, United Baptists, Welcoming and Affirming Baptists, and Unity Baptists.

Given the rise in such non-mainline groups, will the old Protestant churches soon fade away? Their defenders roll their eyes in boredom at assertions that they are approaching irrelevancy. But, frankly, if somebody announced that all 150 of the Shakers left in the U.S. had voted against funding NASA, who would care?

Today’s old mainline Protestant churches have shrugged off such baggage as the inerrancy of the Scriptures and the divinity of Jesus. Their apologists sigh impatiently at any talk of sin or repentance or hell – making the casual observer wonder why they don’t remove the stained glass windows, too – which eventually are going to offend somebody.

Douthat suggests that the Episcopalians and Presbyterians “pause, amid their frantic renovations, and consider not just what they would change about historic Christianity, but what they would defend and offer uncompromisingly to the world. Absent such a reconsideration, their fate is nearly certain: they will change, and change, and die.”

While indignantly denying their impending demise, the Episcopalians quietly voted to sell their Manhattan headquarters because they can’t even pay for its upkeep. Yet, the big media headline was their approval of transgender clergy and homosexual marriage. At their own convention, the Presbyterians seemed headed in the same direction, then hesitated, falling short of the votes needed to embrace same-sex weddings and shunning anybody who does business with Israel.

“At its biannual conference,” reported the Huntington Post’s Robert P. Jones, “the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) debated for more than three hours before narrowly rejecting a bid to modify the definition of marriage in the church constitution as ‘a covenant between two people.’”

“Today the Episcopal Church,” mused Douthat, “is flexible to the point of indifference on dogma, friendly to sexual liberation in almost every form, willing to blend Christianity with other faiths, and eager to downplay theology entirely in favor of secular political causes.” Members have responded by voting with their feet – demonstrating that these are not the issues that draw them to church. Neither is “ecumenism” – trying to unite the old, shrinking Protestant churches.

“During 1960s-era social transformations, conservative laity withdrew money and support from organized ecumenism,” notes Jill Gill on the Religion Dispatches website. “Meanwhile young liberal Christians often left it behind to do social justice work within a secular environment that offered quicker, bolder action. Others comprised a growing exodus of people embracing a post-Protestant ‘spiritual but not religious’ identity, while adults still within the fold bore fewer children than evangelicals. Many secular intellectuals pooh-poohed religion altogether, as the Democratic party excised religious values from its lingo.

“The result: greying mainline denominations struggling to pay bills while facing steady membership and funding declines. Its corollary: an ecumenical movement facing even steeper financial challenges, worsened by the recession. News of a resulting restructuring effort underway in the nation’s historic flagship ecumenical organization, the National Council of Churches, is occasionally met with the query: ‘You mean it’s not dead yet?’”

Nevertheless, religion writers came away from the Episcopal and Presbyterian conventions praising the events. Indignation resounded at Douthat’s and other observers’ assessments. In one of the milder rebuttals, theology professor Sarah Morice-Brubaker chided the Times columnist:

“Ross Douthat is telling stories again. He is a very good and compelling storyteller, which you can tell from the fact that he can tell (beg pardon) an old old story, and somehow it’s still fresh and interesting.

“You probably know this story: it’s about a character called Liberal Christianity, and how it fatuously chased after every faddish cause that came down the pike in a misguided attempt to be relevant and popular. But then – oh, the irony! – it turned out that people who bothered with Christianity actually wanted churches that stood by timeless principles, and so they left. So sad! Now Liberal Christianity is left mostly alone, a victim of its own stinking desperation. For it has become, in his words, ‘flexible to the point of indifference on dogma, friendly to sexual liberation in almost every form, willing to blend Christianity with other faiths, and eager to downplay theology entirely in favor of secular political causes.’”

In the Huntington Post, religion writer Dianna Butler Bass scoffed at Douthat, noting, “In recent days, conservatives have attacked the Episcopal Church. The reason? The church has just concluded its once every three-year national meeting, and in this gathering the denomination affirmed a liturgy to bless same-sex unions. Conservatives assert that the Episcopal Church’s ever-increasing social and political progressivism has led to a precipitous membership decline and ruined the denomination.

“Many of the criticisms were mean-spirited or partisan,” wrote Bass, “continuing a decade-long internal debate about the Episcopal Church’s future. However, Douthat broadened the discussion.

“Douthat insists that any denomination committed to contemporary liberalism will ultimately collapse. According to him, the Episcopal Church and its allegedly trendy faith, a faith that varies from a more worthy form of classical liberalism, is facing imminent death.

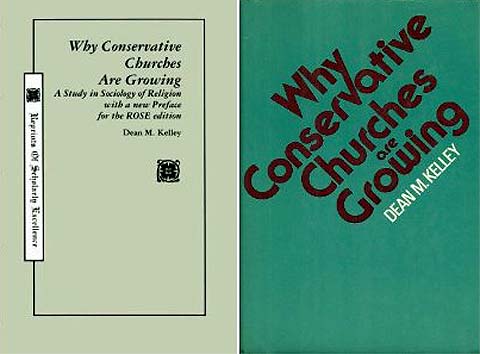

“His argument, however, is neither particularly original nor true. It follows a thesis first set out in a 1972 book, Why Conservative Churches Are Growing by Dean Kelley. Drawing on Kelley’s argument, Douthat believes that in the 1960s liberal Christianity overly accommodated to the culture and loosened its ties to tradition.”

Indeed, “Amid the current neglect and hostility toward organized religion in general,” Kelley wrote, “the conservative churches, holding to seemingly outmoded theology and making strict demands on their members, have equalled or surpassed in growth the early percentage increases of the nation’s population.”

Kelley noted that it had been generally assumed that churches, “if they want to succeed, will be reasonable, rational, courteous, responsible, restrained, and receptive to outside criticism.” These churches would be highly concerned with preserving “a good image in the world” — and that meant especially within the world of the cultural elites. These churches, intending to grow, would be “democratic and gentle in their internal affairs” — as the larger world defines those qualities. These churches will intend to be cooperative with other religious groups in order to meet common goals, and thus “will not let dogmatism, judgmental moralism, or obsessions with cultic purity stand in the way of such cooperation and service.”

However, the opposite is true, wrote Kelley: ‘These expectations are a recipe for the failure of the religious enterprise, and arise from a mistaken view of what success in religion is and how it should be fostered and measured.'”

“That was 1972,” downplayed Bass. “Forty years later, in 2012, liberal churches are not the only ones declining. It is true that progressive religious bodies started to decline in the 1960s. However, conservative denominations are now experiencing the same.”

That justification was repeated in the other attacks on Douthat — claims that now conservative churches are shrinking, too.

“Certainly attendance in the Episcopal church is decreasing, but, as many of the critics of Douthat’s piece have pointed out, church attendance is decreasing across the board,” proclaimed religion writer Jonathan D. Fitzgerald.

The problem with that defense is that the decline at conservative churches is miniscule. Membership loss by the Southern Baptists this year, for example, was cause for concern at their annual convention — but amounted to less than 1 percent.

Why are the defenders of the shrinking Protestant mainline churches so annoyed with this entire discussion — or assertions that they are increasingly irrelevant to anybody but themselves?

For one thing, Douthat had dared to cite yet once again John Shelby Spong’s 1998 book Why Christianity Must Change or Die. “The reliably controversial Episcopal bishop of Newark,” wrote the Times columnist, “was a uniquely radical figure – during his career, he dismissed almost every element of traditional Christian faith as so much superstition – but most recent leaders of the Episcopal Church have shared his premise. Thus their church has spent the last several decades changing and then changing some more, from a sedate pillar of the WASP establishment into one of the most self-consciously progressive Christian bodies in the United States.

“And in the process, they have provoked a historic schism” with entire dioceses going to court attempting to separate their churches from the denomination — and losing. At the convention, the hierarchy reported headquarters had spent $18 million suing its own congregations – forcing them in court to leave behind buildings they’ve built over the last 250 years with their own sacrifices, labor and love. At last count, nine bishops had decried the convention’s actions in a formal statement. Entire congregations have ceremoniously filed out of the buildings they lost in court and walked down the sidewalk to new facilities where they have started again, liberated from the dictates of a headquarters that had dramatically failed them — attempting to force failure and death on their congregations.

“The Episcopalians are hardly alone,” observes Joseph Bottum. “Many commentators, analyzing the decline of liberal denominations in recent decades, have pointed to the gains of conservative churches.” He, again, cites Kelley, who started the discussion of why people go to church. Is it to be told that sins listed in the Bible really aren’t wicked anymore? To hear that the the Bible is a compilation of Babylonian fairy tales? To listen to doubts over whether Jesus rose from the dead? To debate whether it’s OK to appoint as bishop a man married to another man?

No, reported Benton Johnson, Dean R. Hoge, and Donald A. Luidens in their analysis, Mainline Churches: The Real Reason for Decline. “In our study,” they wrote, “the single best predictor of church participation turned out to be belief – orthodox Christian belief, and especially the teaching that a person can be saved only through Jesus Christ.”

The Episcopalians aren’t the only old mainliners vanishing. Disappearing at a record rate are the Disciples of Christ – the liberal branch of the Campbell-Stone Restoration Movement that began on the American frontier during the Second Great Awakening of the early 19th century. That same movement spawned the arch-conservative and militantly locally autonomous Churches of Christ, which remain annoyed with the arch-liberal and shrinking Congregationalists who now call themselves the “United Church of Christ.” The two groups could not be more disimilar.

Some of the conservative Churches of Christ (which as a tenet of faith allow only a capella music) and their just as independent Christian Churches (which do allow musical instruments) insist that the word “church” remain lower case in their names — that Christ alone should receive that honor. The independent Christian Churches decline to organize nationally beyond holding their annual North American Christian Convention. Nevertheless, the two conservative groups are growing in numbers while the liberal Disciples are dwindling.

Similar conservative factions are thriving within the Methodists, Congregationalists, Lutherans and Presbyterians. In January, the Orlando Sentinel reported that members of the First Presbyterian Church of Orlando had voted overwhelmingly to break away from the Presbyterian Church (USA) to join the conservative Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC).

“The 1,759 to 185 vote exceeded the two-thirds majority needed,” reported the Sentinel. “The 3,600-member First Presbyterian is the largest Presbyterian church in Florida and fourth largest in the nation. First Presbyterian has been losing membership in recent years and blamed some of that on PC (USA) doctrines that permitted the ordination of gay deacons, elders and clergy. Some also blamed the decline on doctrines that quest questioned the Bible as the literal word of God and Jesus Christ as the only salvation.”

Unlike the litigious Episcopalians, the Presbyterian Church (USA) released the prestigious congregation – which is now in the process of formalizing its relationship with the more conservative Evangelical Presbyterian Church.

Why make the switch? Local elder Cleat Simmons told the Sentinel “The PC (USA) has turned its back on God and is a denomination dying in the wilderness.”

So, which churches are in trouble? According to Gordon-Conwell’s figures, the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) have suffered a 56.4 percent loss in membership since 1960. The United Church of Christ (Congregationalist) is down 35.9 percent. The Episcopalians have lost 32.6 percent of their members since 1960. The United Methodist Church is down 23.6 percent and the Presbyterian Church (USA) has lost 21.1 percent of its membership.

That’s 6.2 million people no longer sitting in the old mainline pews.

Meanwhile, the Roman Catholic Church has swelled from 42.1 million members to 66.4 million since 1960. The Southern Baptists are up 67 percent in the same period, from 9.7 million to 16.2 million.

Significant growth has been seen in two very conservative and traditionally African-American denominations, the Church of God in Christ (reporting 5.5 million members compared to 393,000 in 1960) and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, reporting a 103% increase from 1.9 million to 3.9 million. The Assemblies of God churches report 2.6 million members, compared to 509,000 in 1960.

And the big boom — spawning many of the new and growing megachurches across the countryside — is in the independents. What’s their secret? They preach the Bible instead of denying it or explaining it away. They also focus on energetic outreaches to youth and young adults — and families.

On the other hand, “Instead of attracting a younger, more open-minded demographic with these changes, the Episcopal Church’s dying has proceeded apace,” noted Douthat. Their defense, he says alternates “between a Monty Python-esque ‘it’s just a flesh wound!’ bravado and a weird self-righteousness about their looming extinction. (In a 2006 interview, the Episcopal Church’s presiding bishop explained that her communion’s members valued ‘the stewardship of the earth’ too highly to reproduce themselves.)”

“When people leave mainline churches, they go somewhere else,” writes Michael De Groote for the Salt Lake City Deseret News. “As Rodney Stark, a sociologist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas describes it, they are not leaving religion so much as they are looking for religion. About 44 percent of Americans say they have a religious affiliation that is different from the religion in which they were raised, according to the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life’s ‘U.S. Religious Landscape Survey.’

“Everybody knows that the so-called ‘mainline’ is now the sideline,” writes De Groote. “’The United Church of Christ, Presbyterians, Methodists and the Episcopalians have been shrinking at a rather prodigious rate. But that isn’t because people left church, it is because people left those churches,’ says Stark. ‘Groups like the Assemblies of God have doubled and redoubled in size in the same period of time.’”

Stark, however, sees the explanation as simple.

“People go to church for religion, not for all these social things. Strange as that may seem. If you get up in the morning and go to a church where religion is not being taken seriously, you go someplace else. I don’t think that is very surprising.”