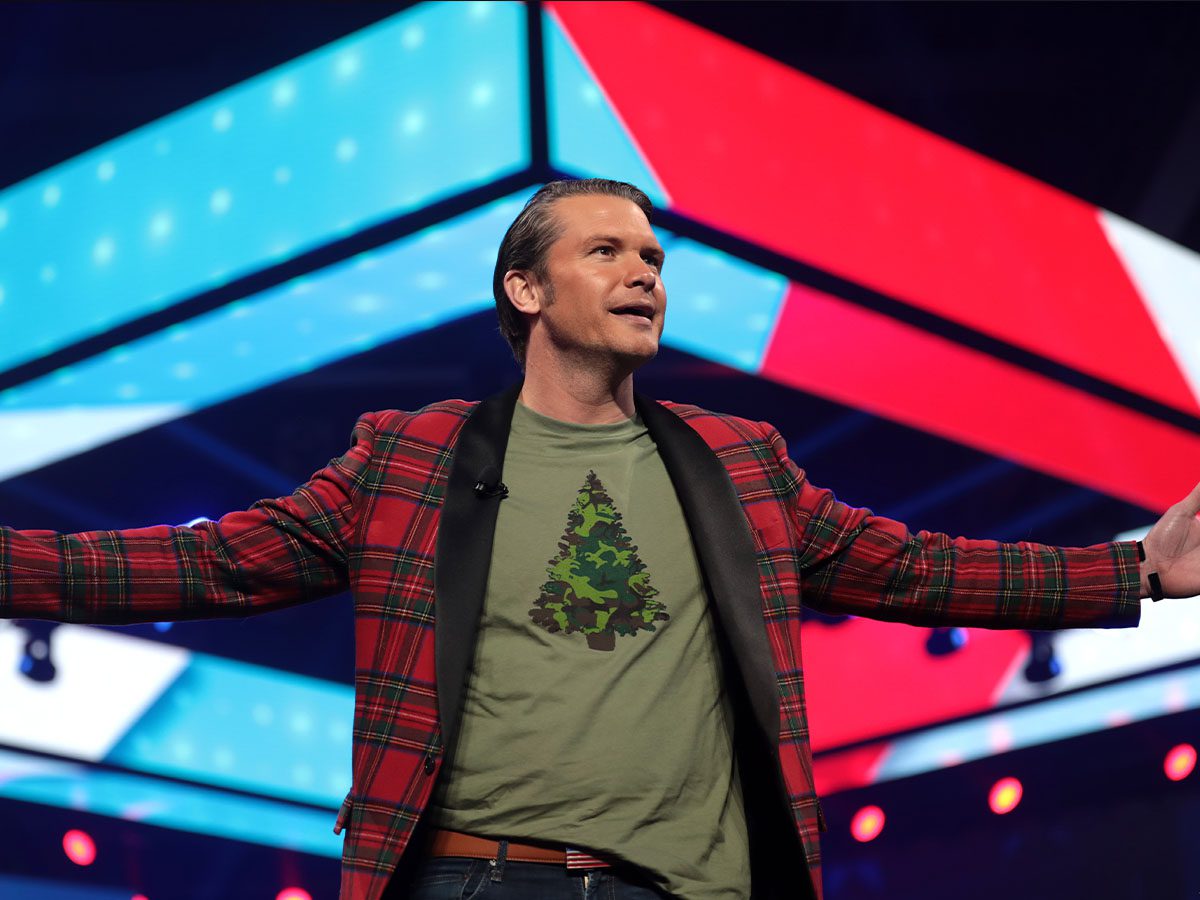

President-elect Donald Trump’s nomination of Fox News host Pete Hegseth to lead the Defense Department marks a significant milestone for a growing faction of the Christian nationalist movement. For members of the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches (CREC), Hegseth’s appointment isn’t just a political victory—it’s a divine affirmation.

The CREC, a denomination championed by Doug Wilson, pastor of Christ Church in Moscow, Idaho, has long advocated for a vision of a society where traditionalist Christian men lead key institutions, including the military. For many in this coalition, Hegseth’s nomination is a powerful validation of their years-long efforts to influence the nation’s political and cultural landscape.

Hegseth’s church, Pilgrim Hill Reformed Fellowship near Nashville, Tennessee, is a member of the CREC. This denomination has expanded rapidly in recent years, appealing to conservative evangelicals disillusioned by mainstream Christianity’s perceived compromises on cultural and political issues.

The CREC, which has added 50 congregations since 2020, emphasizes hypermasculine virtues, patriarchal authority, and a long-term vision for a society governed by biblical principles. Its leaders openly advocate for a theocratic state where Christian men hold sway over government, church, and family life.

Hegseth’s journey into the CREC began with his family’s decision to enroll their children at Jonathan Edwards Classical Academy, a school affiliated with the Association of Classical Christian Schools (ACCS), co-founded by Wilson. From there, Hegseth and his family joined Pilgrim Hill, immersing themselves in a theological framework that emphasizes “sphere sovereignty”—a concept that envisions Christian men wielding authority in distinct but interconnected spheres of society.

For Hegseth, this ideological alignment seems personal as well as professional. In a February podcast interview with Pilgrim Hill leaders, he described his theological awakening:

“My life over the past four to five years has been a Reformation red pill. When you really submit to the reality that God’s law sets you free because it is truth, it’s made me want to understand that law and understand Him even better.”

Hegseth’s nomination has not been without controversy. Critics point to his opposition to women in combat—a stance he has softened recently—as evidence of the hypermasculine ideology at the core of his beliefs. His association with the CREC and its patriarchal worldview has also raised concerns about the implications of his leadership in the nation’s highest defense office.

Some senators critical of his confirmation vote have expressed unease about the alignment of his personal beliefs with his prospective role, particularly given his church’s broader mission to reshape society in its theological image.

The CREC’s influence extends beyond Hegseth. Wilson and other leaders within the denomination have long sought to build institutions that promote their vision of Christian patriarchy and cultural dominance. From New Saint Andrews College to Canon Press, the CREC’s publishing arm, this movement has created platforms to advance its ideals.

Wilson himself has become more politically visible, appearing on national platforms like Tucker Carlson’s show and conservative conferences in Washington, D.C. For Wilson and his followers, Hegseth’s nomination represents a tangible step toward realizing their long-term goals.

Hegseth’s nomination is a significant win for the Christian nationalist movement, particularly the CREC-aligned faction that emphasizes discipline, order, and theological precision. Unlike charismatic Christian nationalists who lean on prophecy and emotional appeals, the CREC approach is grounded in logic and a slow, deliberate strategy for societal transformation.

Matthew Taylor, a religious extremism expert, describes this coalition’s approach as militant:

“They believe the church is supposed to be militant in the world, reforming it and, in some ways, conquering it. Hegseth’s nomination gives them a foothold in the broader political landscape and advances their agenda.”

As Hegseth’s nomination moves through the confirmation process, it will serve as a litmus test for the extent to which this hardline Christian nationalist movement can embed itself within the highest levels of government.

Julie Ingersoll, author of Building God’s Kingdom: Inside the World of Christian Reconstruction, views this development as part of a calculated plan:

“They’re always anticipating these sorts of moves into positions of power for people who see the world the way they do. I don’t think it’s coincidental. I think that’s the plan.”

For proponents like Pilgrim Hill pastor Brooks Potteiger, the nomination is not merely a political milestone but a spiritual victory. In a recent podcast, he described the CREC’s mission as unapologetically offensive:

“We don’t expect to concede any ground; we expect to take the high ground in the culture war.”

Whether Hegseth’s appointment marks the beginning of a new era for the CREC’s vision of Christian governance or a flashpoint for resistance against it remains to be seen. What is certain is that this nomination has already energized a movement committed to reshaping the nation in its theological image, one step—and one leader—at a time.