I like the idea that one should be able to look at another faith and think There is

something in this other religious tradition that I really value and I wish we had it. I can learn something here. The late Krister Stendahl, who served as Professor of Divinity and Dean of the Harvard Divinity School, coined this feeling “holy envy.”

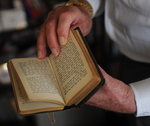

I remember experiencing holy envy while having lunches with my friend Aaron.

Aaron and I would eat together in a small cafe in the lobby of the New York City hospital where we both served as chaplains. A religious Jew, Aaron would dutifully bring his kosher lunch in every day. And every day after we were done eating, he would gracefully but unapologetically excuse himself, pull out a small prayer book, and take some time to re-connect spiritually. I could see that in a matter of moments, the small cafe in the hospital lobby melted away for Aaron and he was able to create a sacred space right there and dive deeply into it.

Aaron and I would eat together in a small cafe in the lobby of the New York City hospital where we both served as chaplains. A religious Jew, Aaron would dutifully bring his kosher lunch in every day. And every day after we were done eating, he would gracefully but unapologetically excuse himself, pull out a small prayer book, and take some time to re-connect spiritually. I could see that in a matter of moments, the small cafe in the hospital lobby melted away for Aaron and he was able to create a sacred space right there and dive deeply into it.

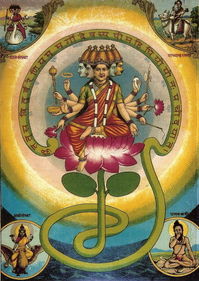

Observing the scene, I found myself wishing that as a Hindu I had something like that, something so grounding and deep. I loved the fact that it followed the act of eating; to me, it seemed to imply that along with feeding the body, Aaron was taking the time to nourish the soul. I was deeply impressed by how consistent, disciplined, and regulated the routine was. And of course, I envied how unapologetic and open the whole thing was — Aaron’s simple act of excusing himself made such a profound statement about how he prioritized his spiritual practice and wasn’t afraid to show it.

As is often the case, I think, the holy envy gave way to a new-found

appreciation for a practice of my own. Some years ago, I took vows and was awarded the sacred thread worn by orthodox Hindu male priests in a ceremony called upanayana.

(This ceremony is something of a cross between a Bar Mitzvah and a

priesthood installation, depending on how you interpret it. Some Hindu

schools consider it more of a rite of passage, awarding it at a younger

age, often on the basis of heredity. Others, like my own, consider it

more a sign of entering the priesthood, and only award it to those who

undergo requisite training and study, regardless of heredity.)

Receiving the sacred thread carries with it a responsibility: three

times a day (at sunrise, high noon, and sunset) one is obligated to

take time out and meditate while silently reciting the famous Gayatri

mantra.

In the months immediately following the ceremony, I performed the

thrice daily Gayatri meditation dutifully. But then, I started to see

it as a mechanical chore. Over the course of time, I began to slip —

becoming inconsistent in my meditation practice, robotically speeding

through the recitation of the mantra, or skipping out on it altogether.

Recently, I’ve been trying to rededicate myself to this practice.

Moreover, I’m trying to appreciate the significance of it. I want to

see those three times a day, not as a chore, but as my private

one-on-one time with the Divine; my opportunity to take a breather from

the world of deadlines and results, and re-center; an opportunity to

mark the sandhya, the transition between one part of the day and the next, and to learn how to simply be in the moment, rather than lamenting on the past or worrying about the future.

I want to nourish the soul.

This way of looking at the Gaytari has, of course, always been there in

Hinduism as well. But sometimes it takes a Jewish friend to remind you

to look for it.