Is Sandra Bullock a success? Well, that depends on a lot of things– and mostly on when you were to ask the question. Seeing her on Oscar night, as she gracefully stepped up to the podium to claim her prize, we might have answered with a resounding “Yes.” After all, that little statue in her hands was a physical manifestation of something far more significant: she had won validation and admiration in the eyes of her peers (who, only a few years ago, had all but written her off as the patron saint of B-grade fluffy romantic comedies).

Is Sandra Bullock a success? Well, that depends on a lot of things– and mostly on when you were to ask the question. Seeing her on Oscar night, as she gracefully stepped up to the podium to claim her prize, we might have answered with a resounding “Yes.” After all, that little statue in her hands was a physical manifestation of something far more significant: she had won validation and admiration in the eyes of her peers (who, only a few years ago, had all but written her off as the patron saint of B-grade fluffy romantic comedies).

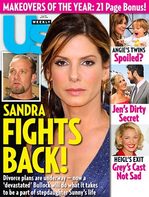

On the other hand, ask the same question just a few days later — as she files for divorce and as the tabloids continue to dish out sordid details of her husband’s affair with a tattoo-covered Nazi-sympathizing lover — and the answer is something very different.

In his insightful op-ed for the New York Times, David Brooks phrases the paradox of Sandra in another way:

Two things happened to Sandra Bullock this month. First, she won an Academy Award for best actress. Then came the news reports claiming that her husband is an adulterous jerk. So the philosophic question of the day is: Would you take that as a deal? Would you exchange a tremendous professional triumph for a severe personal blow?

(read the whole piece here)

Does the juxtaposition of Bullock’s Oscar success and nearly-simultaneous marriage failure tell us something about the way we measure success to begin with? Does 15-year-old bullying victim Phoebe Prince’s suicide warn us of where our unhealthy paradigms take us? Might our skewed definition of success be at least partly to blame? And might the wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita offer us an alternative?

When we saw Sandra Bullock with her Oscar, or read the reports of how many millions she was worth, or toured her palatial homes via reality TV shows, or simply marveled at her flawless skin and sparkling white smile projected on to a movie screen, we were quick to decide that she was succesful.

When we saw Sandra Bullock with her Oscar, or read the reports of how many millions she was worth, or toured her palatial homes via reality TV shows, or simply marveled at her flawless skin and sparkling white smile projected on to a movie screen, we were quick to decide that she was succesful.

Now that we know that Sandra Bullock’s marriage to bad-boy Jesse James has publicly crashed and burned, we are equally quick to brand her a failure.

Our measure of success it seems, is pretty fickle.

First, its tied to the material and quantifiable. We can count it and point to it — whether in the currency of prestigious awards and accolades or simply in terms of cold, hard cash flow.

We don’t just do that with celebrities. We apply it to ourselves: we march along, filling up resumes and portfolios and profiles with mountains of stuff that we can point to, and say: “There, see that? See that collection of impressive, shiny things I’ve acquired. That proves that I’m worthy of your validation.”

Sounds pretty crazy, huh? And yet we do it, and we do it relentlessly.

Our measure of success (Sandra’s or, by extension, our own) has more to do with what one does than with who one is. It has to do more with making a living, than with living a life. We busy ourselves in chasing the awards and bonus checks, often at the expense of the very things that we know will truly make us happy. Referencing some recently conducted research about the relationship between personal and professional happiness, David Brooks sums it up nicely:

…[M]ost of us pay attention to the wrong things. Most people vastly overestimate the extent to which more money would improve our lives. Most schools and colleges spend too much time preparing students for careers and not enough preparing them to make social decisions. Most governments release a ton of data on economic trends but not enough on trust and other social conditions. In short, modern societies have developed vast institutions oriented around the things that are easy to count, not around the things that matter most. They have an affinity for material concerns and a primordial fear of moral and social ones.

Our sense of success is also rooted — embarassingly so, if we are honest — in the superficial and temporal. What really surprised us about the Jesse James affair scandal was how soon it hit after poor Sandra’s win. But in one sense, it just sped up the inevitable. At a certain point, the summer of Bullock’s success would have to give way to colder weather. If not a personal blow, then it might have been legal troubles, or a box-office flop (Miss Congeniality Part III?), or simply the ravages of time. When we base our succsess on the here-and-now, as we so often do, we set ourselves up for the flip-side of the coin– inevitable failure. Neither lasts forever.

And on some level or another, our notions of success and failure are deeply connected to our tendency to compare ourselves against one another. To win an award, for instance, is really to win the recognition that (directly or indirectly) I am certifiably better than others. My success, then, is by its very definition a celebration of your failure.

Of course we rarely talk about this aspect of success or care to admit it. But it is there within us, even in our treatment of Ms. Bullock. Pre-affair, we celebrated her but also envied her. Perhaps we viewed her win as a goal to aspire towards. Perhaps we held her up as a standard for beauty, or talent, or of a certain desirable lifestyle. “She has it all,” we may have said wistfully, reminding ourselves of the painful fact that we simply don’t.

Then when the bad news hit, we swung our pendulums the other way, towards pitying and analyzing her from the safety of the sidelines. “Tsk, tsk… I guess all that glitters isn’t gold after all,” we said, even as we couldn’t pull ourselves away from the tabolid coverage. And secretly, of course, in her failure we also compared ourselves to her, and perhaps felt the sweet pangs of relief– “I may not have an Oscar, but at least my husband’s not a two-timing jerk.”

In other words, whether in success or failure, we’re still applying the same warped rules to the same dysfunctional game.

Its a game that can end in deadly tragedy.

Consider the case of 15-year-old suicide victim Phoebe Prince, who hanged herself in January, reportedly after enduring months of tormenting bullying by her peers. Prince had moved to Massachusetts from Ireland, and was quickly made the target for a group of students at her new school who seemed to delight in putting her down.

The DA’s office is now prosecuting her bullies for a host of crimes, trying to hold them accountable for driving her to take her own life.

The DA’s office is now prosecuting her bullies for a host of crimes, trying to hold them accountable for driving her to take her own life.

Its easy to feel sorry for Phoebe. But can we do better than that? Can we try to imagine how painful her life had become for the high school freshman to make the drastic and irreversible decision to end it? Can we begin to fathom the intensity with which Phoebe must have been desperate for even the slightest acceptance and validation from her peers? Or how crushing her sense of failure must have been when that validation and acceptance never came?

High school, you may remember, is probably the singlemost critical formative period when it comes to defining the terms of success and failure. Teenagers learn the rules of the game in a brutally turbo-charged microcosm of the real word. Few ever really feel “good enough.” The studious compete for honors and ranking. The athletic compete for bragging rights. The fat kid wants nothing more than to be skinny. The skinny kid wants to bulk up. The ugly duckling defines success as becoming the pretty swan.

Ironically, by all reports Phoebe Prince was a pretty girl who had even won the affections of a popular senior for some time. In fact, it was this brief shot at popularity that seems to have been the initial cause for her to be targeted. She was swiftly and mercilessly branded a “slut” and an outsider. Perhaps she was punished for her attempts at success, her tormentors deciding that they had to put her in her place.

Bullying is one particularly disturbing and unhealthy way that people cope with their own sense of failure. Bullies project their own weaknesses and insecurities on to their victims, mistreating others as a way to compensate for their own emptiness and lack of validation. Dr. Keith Ablow seems to think this may be at the root of Phoebe’s bullies:

Bullies are good at detecting victims who feel things deeply or who are unsure of themselves because, underneath it all, they are on the run from their own feelings and uncertain of their own worth. That’s why they band together and go on the offense as a group. They can pretend to be more valuable than their targets and less vulnerable….

In the age of the Internet and Facebook, more teens than ever are busy getting the surface of their lives to look good, while their inner, emotional lives are built on the most fragile ground imaginable. Bullying, like all drugs, can become epidemic in such circumstances.

(read more here)

The bullies must have fed off of one another, impressing one another with increasing levels of cruelty, giving eachother the validation and justification they were so obviously starved of. They probably zeroed in on Phoebe’s insecurities and weaknesses, her fears about not being good enough or liked enough or respected enough, and ruthlessly exploited those weaknesses to pull Phoebe down. And the saddest (and perhaps sickest) part of it all is that in the final equation, their actions probably had very little to do with Phoebe Prince herself, and everything to do with their own insecurities, weaknesses, and failure.

Phoebe Prince’s tragic death is a wake-up call about bullying, yes. And we may look at Sandra Bullock’s quick journey from Oscar night Heaven to her own personal Hell as a cautionary tale about the value of personal relationships over material accomplishment. True enough.

But both of these stories also speak to a larger problem: our very metric for success is out of whack. The whole system — the system that Phoebe Prince relied on, the system that Phoebe’s bullies operated within, the system that make Sandra Bullock and Jesse James headline news, and the system that keeps us glued to those headlines — is broken.

The Bhagavad Gita offers us a very different metric for success. “Act in accordance to dharma” Krishna tells Arjuna, “abandoning all attachment to the success and failure of this world. Such equanimity is called yoga.” (Bhagavad-Gita 2.48) And one of the first instructions Krishna gives in the Gita makes the same point: “Dualities in this world like happiness and sadness, or success and failure, are like the coming and going of winter and summer seasons. They arise from perception, and one must learn to remain steady despite them.” (Bhagavad Gita 2.13) How? By cultivating depth within. And ultimately, by learning to see the Divine in everything and everything in the Divine.

Krishna’s metric for success, real success beyond the flickering variety of success and failure we experience in the world, is to strive to have this vision. If we make sincere efforts to base our actions on this framework, then we will have achieved Success (with a capital “s”), beyond the wins and losses of the material world.

This is more than a truism; it is a call to radically change the way we look at success. The Gita offers a whole lifestyle — a whole new paradigm really — to help us to make that radical change.

It is far from easy, to be sure. But to continue along with the alternative, we are beginning to see, is downright impossible.