Growing up, I always experienced Halloween as a clashing of cultures. More than any other American holiday, Halloween seemed to draw a line in the sand between the world that my Hindu immigrant parents resided in and the American suburban world around me. Since Halloween usually tends to coincide with a number of Hindu holidays (Hindus use a lunar calendar, so exact dates switch around), when Diwali happened to fall on October 31, the two holidays went head-to-head. Either I could go trick-or-treating and watch the Nightmare on Elm Street marathon (my desire), or visit temple and exchange sweets with relatives (my parents’ orders), but I couldn’t really do both.

Even when there wasn’t a direct conflict, though, there was always a disconnect.

“What kind of depressing holiday is this supposed to be, anyway?” my Mom would ask, disapproval in her voice as she suspiciously surveyed the plastic skeletons and cardboard tombstones now decorating our neighbors’ lawns. “A waste of time,” my father would mutter even as he begrudgingly bought bags of cheap candy to hand out to trick-or-treaters.

(Some of their more orthodox Hindu friends had even stronger objections to the holiday. “All this meditating on death and gore, and openly celebrating ghosts and goblins! It’s ashubh, inauspicious.”)

My parents tried, of course, but somehow they were never able to quite get it. Sure, they proudly displayed the jack-o-lanterns that my sister and I carved at school; but we’d never carve one together as a family. They dutifully doled out the candy to the neighborhood kids, though without the gusto of the other parents, who’d often dress up themselves and distribute treats in character. And of course, they were content to let us go out trick-or-treating, though I can’t really remember them getting too excited about it.

And then there was the issue of costumes.

Most years — as long as it wasn’t too expensive — we could just convince them to buy whatever superhero or horror movie monster costume was popular that year.

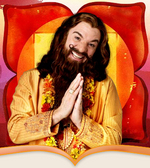

But there were those years that our parents (and other Desi parents, I’ve since learned) stumbled across what they thought was brilliance– to have us dress up as an “Indian prince” or “Indian princess”. This feat in creative laziness they accomplished by dolling us up in our finest Indian party clothes, perhaps with the addition of a makeshift turban or tiara, and sending us out to impress our candy-giving neighbors with our exotic apparel.

The neighbors loved it, our parents felt the euphoric mix of cultural pride and saving money, and we (the Association of Involuntary Indian Princes and Princesses) thought that it was incredibly lame.

(Full Disclosure: Years later, when we were old enough to see trick-or-treating only as a means to free candy, but still young enough to get away with it, we Indian-American kids co-opted this tactic by willingly donning our kurta pyjama or salwar kameez outfits to feed our candy fix without going through the trouble of actually buying a costume.)

As much as we resented it, though, now that I look back at it, I can appreciate a certain mingling of cultures that it engendered. And now that I am a parent myself, I wonder about how to minimize the culture clash for my own Indian-American daughter, and how to integrate the worlds of Halloween and Hinduism for her.

I was discussing this with a Christian colleague yesterday, and he

asked what I thought about having kids dress up as Hindu deities. I

have to admit, his question caught me off guard. A bindi-wearing Indian Princess is one thing, but dressing up like a goddess…?

The

more I thought about it, though, the less sure I became of how I felt

about the whole thing. Would it be a celebration of Hinduism’s rich

imagery, or a mockery of faith? Would it provide a chance for Hindus to

share their faith and beliefs with others, or just fuel stereotypes and

marginalize Hindus? And how would the Hindu kids themselves feel about

it, anyway?

On the hand, there is precedent for dressing

On the hand, there is precedent for dressing

up as deities in Hinduism. Many parents dress their children up as Lord

Krishna on Krishna Janmashtami. Ramleela — dramatic re-enactments of

Lord Rama’s epic pastimes — also involve children and adults donning

costumes to depict figures such as Lord Rama, the brave Hanuman, or the

dastardly demon king Ravana. There’s even a Bengali tradition of

dressing up as the goddess Kali — blood-red tongue, carrying a

machete, and wearing a garland of skulls — for the holiday of Kali

Puja every October/November; undoubtedly, the closest direct link

between Halloween and Hinduism I’ve found yet .

And some

And some

Hindu temples have started using Halloween as a way to connect Hindu

kids withe their culture. Our local Krishna temple in New Jersey is

hosting a children’s costume contest on Halloween, where the kids are

invited to depict any character from Krishna’s life story.

On

the other hand, does it make a difference when the Hindu deity costume

is taken out of the context of a Hindu holiday (or a temple-sponsored

costume pageant), and mapped on to the American Halloween mainstream?

Does it denigrate Hinduism to have a portrayal of Lord Krishna

soliciting candy door-to-door alongside Spiderman or Harry Potter? Are

we putting divinity in the same character as fictional superheroes or,

worse yet, freaks and creatures that only get to come out into the

light of day once a year? And what does that communicate about Hinduism

among other faiths? How would we feel about children dressing up like

Jesus or Buddha or Mohammed for Halloween?

And what if Hindu

And what if Hindu

costumes became popular enough to attract the attention of non-Hindus?

Does that change things? Is it okay to wear a costume depicting the

goddess Kali because you think her look is “gruesome” and “cool” even

if you don’t believe in her?

Hollywood actress Heidi Klum seemed

Hollywood actress Heidi Klum seemed

to think so last year, and got slammed for it. In a thoughftul blog

post about the bruhaha, Sayantani Dasgupta tried to articulate why

Klum’s costume choice rubbed her the wrong way:

…I realize that my anger at Heidi’s choice of costume is not about religion as much as it is about racism. Kali

is a living goddess – living in the sense that she is actively

worshipped as a manifestation of the feminine force which can take life

as well as give it. Kali is living in that her symbolism

– whether as a goddess of ferocious destruction or of redemptive change

– is integrated into the culture of an entire subcontinent.Despite Heidi Klum’s obvious confusion, Kali is neither a plastic skeleton nor a dime store pirate. She is not a saucy serving wench nor a vixenish she-devil. By

turning a religious and cultural symbol into a freakish if dramatic

Halloween spectacle, Klum has enacted the most base sort of cultural

appropriation.

As much as I’d love to see more integration on October 31, I can’t help but share Dasgupta’s concerns about “turning a religious and cultural symbol into a freakish spectacle.”

I’m still undecided about “Hindu-izing” Halloween. What do you think?

Oh,

and in case you were wondering, my daughter will be dressed up as a

chubby little pumpkin for her first Halloween this year. Or maybe, just

maybe, an Indian Princess.