The 100th birthday of cartoonist Al Capp, has come and gone, ignored by the hundreds of newspapers that used to carry his satirical daily comic strip “Li’l Abner.”

The 100th birthday of cartoonist Al Capp, has come and gone, ignored by the hundreds of newspapers that used to carry his satirical daily comic strip “Li’l Abner.”

In today’s politically correct environment, Capp’s centennial quite a few months ago didn’t rate mention since he was a iconoclast who mercilessly made fun of such popular heroes as Franklin Roosevelt, Lyndon Johnson and Teddy Kennedy.

His comic strip began in 1934, when the 25-year-old cartoonist had an idea for a daily comic strip featuring hillbillies. He’d just spent several years ghostwriting “Joe Palooka,” a popular strip by cartoonist Ham Fisher, who hired Capp when he ran out of ideas.

Capp’s new strip starred Li’l Abner Yokum, the simple and muscular, poor but lazy, uneducated but good-natured hero of Dogpatch. Abner lived with Mammy and Pappy Yokum and devoted much of his energy into avoiding matrimony with the beautiful and industrious Daisy Mae, his devoted and ever-faithful girlfriend.

Capp’s new strip starred Li’l Abner Yokum, the simple and muscular, poor but lazy, uneducated but good-natured hero of Dogpatch. Abner lived with Mammy and Pappy Yokum and devoted much of his energy into avoiding matrimony with the beautiful and industrious Daisy Mae, his devoted and ever-faithful girlfriend.

Finally during the 1950s, Capp surrendered to pressure from the strip’s millions of daily fans and let the couple marry. Their wedding was such a national event that the happy couple made the cover of Life magazine.

When it debuted, Li’l Abner was picked up by only eight newspapers. However in the midst of the Great Depression, the poor but always hopeful Dogpatchers were a nationwide hit. Within three years, their daily adventures had an audience of 15 million readers. At the peak of their popularity, the strip appeared in over 500 newspapers with a combined circulation over 60 million – when the entire population of the United States was about 180 million.

When it debuted, Li’l Abner was picked up by only eight newspapers. However in the midst of the Great Depression, the poor but always hopeful Dogpatchers were a nationwide hit. Within three years, their daily adventures had an audience of 15 million readers. At the peak of their popularity, the strip appeared in over 500 newspapers with a combined circulation over 60 million – when the entire population of the United States was about 180 million.

Capp created hilarious cartoon characters based on his travels in the mountains of Appalachia. “It featured wildly outlandish characters, bizarre situations and equal parts suspense,” writes Stefan Kanfer in City Journal.

Filled with “slapstick, irony, satire, black humor and biting social commentary, Li’l Abner is considered a classic of the genre,” writes Kanfer.

‘Yokum’ was a combination of yokel and hokum.

Capp apparently did not know that “Yocum” was actually a common surname in the rural Ozarks, an area that embraced the characters as their own and eventually hosted a theme park at a rural Arkansas town that officially changed its name from “Marble Falls” to “Dogpatch.”

Capp apparently did not know that “Yocum” was actually a common surname in the rural Ozarks, an area that embraced the characters as their own and eventually hosted a theme park at a rural Arkansas town that officially changed its name from “Marble Falls” to “Dogpatch.”

The Yokums lived in what would be described as “an average stone-age community” which consisted of ramshackle log cabins, pine trees, “tarnip” fields and “hawg” wallows.

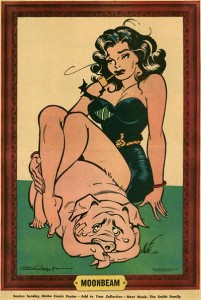

Capp filled his comic strip with an assortment of memorable characters, including Marryin’ Sam, Hairless Joe, Lonesome Polecat, Evil-Eye Fleegle, General Bullmoose, Lena the Hyena, Senator Jack S. Phogbound, Washable Jones, Nightmare Alice, Earthquake McGoon, and a cast of women like Daisy Mae, Wolf Gal, Stupefyin’ Jones and Moonbeam McSwine, who preferred the company of pigs to men.

Capp filled his comic strip with an assortment of memorable characters, including Marryin’ Sam, Hairless Joe, Lonesome Polecat, Evil-Eye Fleegle, General Bullmoose, Lena the Hyena, Senator Jack S. Phogbound, Washable Jones, Nightmare Alice, Earthquake McGoon, and a cast of women like Daisy Mae, Wolf Gal, Stupefyin’ Jones and Moonbeam McSwine, who preferred the company of pigs to men.

They became a part of American culture. Capp’s women found their way onto the painted noses of bomber planes during World War II and the Korean War.

“Another famous character was Joe Btfsplk, ‘the world’s worst jinx,’ bringing bad luck to all those nearby. Btfsplk always had an dark cloud over his head.”

Dogpatch residents regularly combatted the likes of city slickers, business tycoons, government officials, and intellectuals with their homespun stupidity. Situations often took the characters to other destinations, including New York City, Washington, D.C., Hollywood, tropical islands, the moon, Mars and some purely fanciful worlds of Capp’s invention.

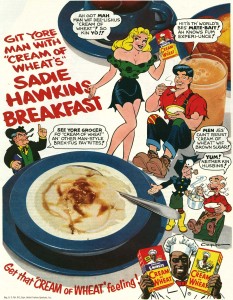

The latter included Lower Slobbovia, which entered the American vocabulary. In his book The American Language, H.L. Mencken also credited Capp with inventing the terms “double whammy,” “skunk works,” “Sadie Hawkins Day,” “druthers,” “schmooze” and “nogoodnik.”

The latter included Lower Slobbovia, which entered the American vocabulary. In his book The American Language, H.L. Mencken also credited Capp with inventing the terms “double whammy,” “skunk works,” “Sadie Hawkins Day,” “druthers,” “schmooze” and “nogoodnik.”

“When Li’l Abner made its debut in 1934,” remembers historian Coulton Waugh, “the vast majority of comic strips were designed chiefly to amuse or thrill their readers. Capp turned that world upside-down by routinely injecting politics and social commentary into Li’l Abner. The strip was the first to regularly introduce characters and story lines having nothing to do with the nominal stars of the strip.

Capp “called society absurd, not just silly,” wrote Rick Marschall in the book America’s Great Comic Strip Artists, “human nature not simply misguided, but irredeemably and irreducibly corrupt. Unlike any other strip, and indeed unlike many other pieces of literature, Li’l Abner was more than a satire of the human condition. It was a commentary on human nature itself.”

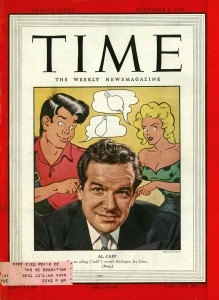

Capp appeared on the cover of Time in 1950. He was a regular guest on NBC’s “The Tonight Show,” interviewed over the years by Steve Allen, Jack Paar and Johnny Carson.

One memorable story, as recounted to Johnny Carson, was about his meeting with then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower. As Capp was ushered into the Oval Office, his prosthetic leg suddenly collapsed into a pile of disengaged parts and hinges on the floor.

The President immediately turned to an aide and said, “Call Walter Reed Hospital,” to which Capp replied, “Hell, no, just call a good local mechanic!”

On the Dick Cavett Show, Capp taunted musician Frank Zappa about his long hair, asking Zappa if he thought he was a girl. Zappa gestured toward Capp’s wooden leg and asked if he thought he was a table.

Vice President Spiro Agnew urged Capp to run in the Democratic Party Massachusetts primary in 1970 against Ted Kennedy for Kennedy’s U.S. Senate seat.

Vice President Spiro Agnew urged Capp to run in the Democratic Party Massachusetts primary in 1970 against Ted Kennedy for Kennedy’s U.S. Senate seat.

Capp died in 1979. However, he had so antagonized a few key, but thin-skinned opinion-makers that there were complaints in 1995 when Li’l Abner was honored with a United States Postal Service commemorative postage stamp.

And so it is at his centennial that the media has yawned in disinterest.

In death, he remains in exile, a sinner who broke from the politically correct fold.