Sitting alone in a Chinese jail cell gives poet and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo plenty of time to contemplate.

Sitting alone in a Chinese jail cell gives poet and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo plenty of time to contemplate.

“Faraway place,” he writes in Experiencing Death,

“I’ve exiled my life to

“this place without sun

“to flee the era of Christ’s birth

“I cannot face the blinding vision on the cross

“From a wisp of smoke to a little heap of ash

“I’ve drained the drink of the martyrs …”

“I’ve exiled my life to

“this place without sun

“to flee the era of Christ’s birth

“I cannot face the blinding vision on the cross

“From a wisp of smoke to a little heap of ash

“I’ve drained the drink of the martyrs …”

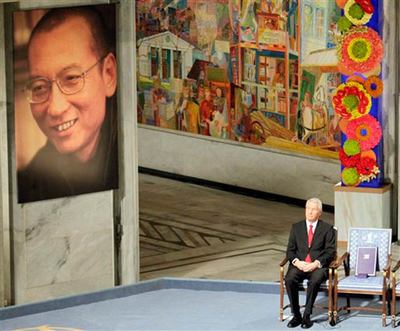

Liu was the recipient of the 2010 Peace Prize, but was forbidden to travel to the award ceremony. He is serving an 11-year prison sentence in the People’s Republic of China for his pro-democracy activities.

In the 1980s, he called for democratic reforms and the end of one-party rule in China. He has been jailed repeatedly and currently is serving his fourth prison term, this time an 11-year term on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.”

Liu was born in Changchun in 1955 to an intellectual family. In the 1980s, he wrote a series of academic essays, Critique on Choices – Dialogue with Li Zehou and Aesthetics and Human Freedom, which earned him fame in the academic field. The first essay criticised the philosophy of a prominent Chinese Communist leader Li Zehou.

Between 1988 and 1989, he was a visiting scholar at several universities outside of China, including Columbia University, the University of Oslo and the University of Hawaii.

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests he was in the United States but decided to go back to China to join the movement. There as it became obvious the government was not going to give in, he persuading students to leave the square, saving hundreds of lives.

He took refuge in the Australian embassy but could not bear to remain in a safe place while citizens and students who had taken part in the movement were being hunted down, arrested and executed. He was arrested while cycling in Beijing and spent the next 20 months in Qincheng prison.

It was a different Liu who left the prison: “My eyes were opened by the death of the martyrs and now, every time I open my mouth, I ask myself if I am worthy of them.”

He was imprisoned again from May 1995 until January 1996 after calling on the government to admit its wrongdoings in the Tiananmen Square student protest.

Eight months later, he was jailed for three years from October 1996 until October 1999, charged with “disturbing the social order.” When he was released in 1999, the government built a sentry station next to his home and his phone calls and internet connections were tapped.

In 2004 when he started to write a Human Right Report of China at home, his computer, letters and documents were confiscated by the government.

He once said that at his wife’s birthday, “her best friend brought two bottles of wines to my home but was blocked by the police to come. I ordered a cake and the police also rejected the man who delivered the cake to us.

“I quarreled with them and the police said, ‘it is for the sake of your security. It has happened many bomb attacks in these days.'”

In 2004, the international group Reporters Without Borders honored Liu’s human rights work, awarding him the Fondation de France Prize as a defender of press freedom.

In December 2009, he was sentenced for 11 years for “spreading a message to subvert the country and authority.” He is currently imprisoned in Jinzhou Prison in Liaoning Province.

After the announcement of his Nobel Peace Prize win, nearly 40 Chinese legal scholars, dissidents and underground church organizers were detained, roughed up, harassed or kept from leaving their homes — all warned not to talk to the western press.

“In the week after Liu won the Prize for his decades of promoting democratic change in China,” reports one western news agency, “dozens of Chinese who openly agreed with his views were hit by a massive police crackdown.

“The latest appears to be a woman who Liu has said should win the prize, Ding Zilin, who has fought for years for China’s government to recognize the hundreds killed in the military’s crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in 1989.”

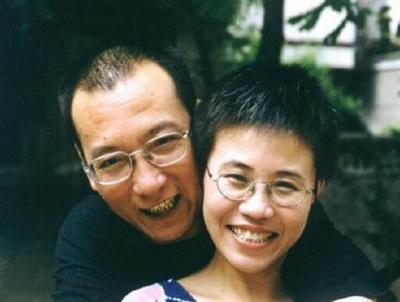

Liu’s wife, Liu Xia, was detained incommunicado at her home. However she did manage to get out an email message in which she asked more than 100 Chinese rights activists to attempt to go to Oslo to collect the prize on her husband’s behalf on December 10.

Liu’s wife, Liu Xia, was detained incommunicado at her home. However she did manage to get out an email message in which she asked more than 100 Chinese rights activists to attempt to go to Oslo to collect the prize on her husband’s behalf on December 10. Several did, but the Nobel Committee opted to leave Liu’s chair symbolically empty during the ceremonies.

Inside China, the Communist-controlled news media at first ignored the story.

“It was really weird,” said an American who works in Shanghai. “I had been watching the announcements of the Nobel Prizes for science, literature and economics, but I realized I hadn’t heard a word about the Peace Prize.”

However, the word got out. Although the Communist government attempts to control the flow of information, computer hacking and electronic gadgetry are national pastimes. Devices to subvert the government’s blocking of the Internet are sold freely on the street.

As a result, many Chinese sidestep their government’s attempts to censor satellite TV news and such Internet sites as Google, YouTube and Facebook. As a result, the Chinese government then turned to attacking Liu as well as the Nobel committee.

Beijing also singled out the Norwegian government for its “erroneous support” of the Nobel Committee’s decision, canceling several meetings with a visiting Norwegian official.

Beijing also singled out the Norwegian government for its “erroneous support” of the Nobel Committee’s decision, canceling several meetings with a visiting Norwegian official.Communist government sprang into action, having a spokesman condemn the award, erasing online mentions of Liu from and pumping up the propaganda in the state media.

One well-known pro-democracy blogger, Wen Yunchao, said a Twitter-like service run by the Chinese-owned Sina Corporation was so deluged with messages that extra employees were brought in to help censor them.

In San Francisco, New York and London, Chinese exiles picketed Chinese embassies in protest.

A pair of official Xinhua News Agency articles, placed prominently on major online services, attacked the prize as a tool the West is using to undermine China.

A pair of official Xinhua News Agency articles, placed prominently on major online services, attacked the prize as a tool the West is using to undermine China. “A few people abroad have reacted to the news with joy, frolicking around as though they’ve taken drugs,” reported one government-released article. “One of these people is the Dalai Lama, who won the Peace Prize in 1989. What’s the underlying link? The Dalai Lama and Liu Xiaobo are the political dolls of Western forces.”

However, the government’s main focus was to keep Chinese democracy spokespersons away from TV news cameras.

Chinese legal scholar Teng Biao said some of his friends were physically prevented by policemen from meeting foreign reporters. Another lawyer, Li Fangping, was told that until further notice he could leave his home only in a police car.

From prison, Liu told his wife he was dedicating the peace prize to the democracy movement’s “lost souls” – those who have lost their lives in the fight for freedom.

“I’m so sorry. I have a lot to say, but I don’t dare to talk. I’ve been confronted several times by police already since Liu Xiaobo won the prize,” said writer Zhao Shiying, who signed Charter 08, Liu’s most famous writing, a manifesto demanding democratic reforms.

“Anyone who signed the charter” is getting police attention, he said. “I hope you understand this life we lead.”

Representatives from the Roman Catholic Justice and Peace Commission of Hong Kong and the Christian Concern Hong Kong Society joined activists seeking his release.

Po Kam Cheong, General Secretary of the Hong Kong Christian Council, said he was overjoyed when he heard of Liu’s winning the prize — and hoped the government would shorten his prison sentence.

In Beijing, China’s foreign ministry said in a statement that Liu is a criminal, and that he has nothing to do with the spirit of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Recently China sentenced 10 Christian leaders to long prison terms and forced labor camps as part of a wider government crackdown.

Five leaders, Li Shuangping, Yang Hongzhen, Yang Caizhen, Gao Qin and Zhao Guoai, received sentences of two years “re-education through labor camps,” according to the advocacy group China Aid Association.

They were sentenced for “gathering people to disturb the public order” when organizing a prayer rally. Pastors Yang Rongli, Wang Xiaoguang, Yang Xuan, Cui Jiaxing, and Zhang Huamei were sentenced up to seven years in prison for “illegally occupying farming land” and “disturbing transportation order by gathering masses.”

“Sister Yang Rongli received a seven years sentence on both charges,” said China Aid. “For the first charge, Pastor Wang received three years, brother Yang Xuan three and a half years and Cui Jiaxing four and a half years. Sister Zhang Huamei was found guilty of the second charge and sentenced to four years in prison.”

China claims Christians are free to worship within state-registered official churches. However observers say many of the country’s estimated 130 million Christians prefer to worship outside control of the Communist government.