One hot August evening in 1963, my Dad, the preacher, my Mom and I gathered after dinner around our old black-and-white TV to watch the news. Flickering on the screens in shades of gray was a recap of something they called the “March on Washington.”

I paid particular attention to the occasionally fuzzy image of 200,000 mostly African-American people packed into Washington, D.C.’s National Mall — not because, at age 10, I recognized the historical civil rights watermark playing out on the NBC Evening News; rather, it was because I noticed my Dad was intently watching. His expression told me, this is important.

On screen was another preacher, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “I have a dream,” he said many times, but the one time that stuck out to me then as a boy was the refrain, “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Dad nodded, quietly. It seemed a moment of introspection for him, so I asked by kid question of Mom, instead. “What’s he mean by ‘content of character?”

She paused, thought and answered: “Well, that Negro children should be judged just like everyone else, by what they do, not because they have black skin.”

We lived in eastern Washington, in the early ‘60s hardly a melting pot –unless you figured that having Scots-Irish, Germans and a few local Native Americans in the same county was diverse. Then, I could have counted the number of black Americans I’d seen in person on one hand. (There also was Mahalia Jackson, the gospel singer whose vinyl LPs my folks had bought. She was on the jacket cover, shiny, ebony and delightfully mysterious. As a boy I often looked at the cover, wondering how this lady was different, and the same as some of my portly, paler aunts).

Still, it was that moment when I awoke to racism. I didn’t know the word itself, yet; but I was upset that any other boys and girls weren’t getting a fair shake because their skin was darker than mine. “That’s not fair,” I said.

Dad looked at me, his eyes softening as he half smiled. Mom agreed, “No, it’s not. Jesus loves all children, just like the song says, Bobby. ‘Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight.'”

In the coming years, I always took notice when Dr. King showed up on TV, leading a boycott here, marching for civil rights there, and in 1968, becoming a leading voice in opposition to the quagmire that the Vietnam War had become. By then, I had another hero to add to Dr. King, Robert Kennedy, who was ramping up to run for the presidency on an anti-war platform.

I was stunned when, on April 4, 1968, the TV news reported that Dr. King had been shot dead in Memphis. Three months later, I watched JFK go in an instant from a triumphant speech after winning the California Democratic presidential primary to lying mortally wounded on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. This is what I saw that night.

Heart-broken, I wept. Hope had twice, in space of a spring and summer, been crushed. Anti-war demonstrations turned into riots, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago turned into open warfare in the streets. We had lost our way.

The fractured Democrats couldn’t stop Republican Richard Nixon’s return to the White House, and Vietnam did finally come to a sad, bloody end.

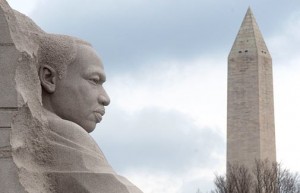

Now, 48 years after he captivated the imaginations of millions with his soaring, hopeful address in the National Mall, our country has dedicated a stone monument there to Rev. King. This larger-than-life memorial to his eloquent call to make the Dream true for all America’s children, will stand long after I am gone; indeed, long after the last of us who heard his words in 1963 are ourselves memories.

May we now, and in generations to come, all look into the carved visage of the man and ask ourselves how each of us can make the Dream lives in our hearts, and resonates in our lives.