There was a time when wearing religious garb or jewelry was seen as an innocent, even admirable testimony of faith.

A cross or crucifix around the neck meant at least some level of commitment to Christ and his teachings. A yarmulke was symbolic of an Orthodox Jew’s respect for the “Divine Presence” above us all. A Muslim woman’s hijab, or a nun’s habit, alike spoke of modesty and submission to their ideas of God.

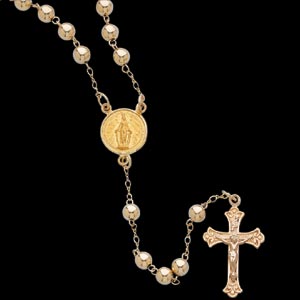

And if you saw someone with rosary beads? That identified them as a devout Catholic who took prayers seriously enough to count them off, a discipline and commitment of the spirit.

Things have changed, at least in the case of crosses, crucifixes and rosary beads. While these items continue to have meaning for many, for others they have become mere items of a jewelry, or even a means to identify decidedly evil intent that is the opposite of their origins.

In Fremont, Nebraska, a school district even went so far recently as to ban a rosary-style necklace after police told them it had become a symbol not of spirituality, but criminal gang membership.

I understand the intent, here: protecting students. Other schools have similarly banned baggy pants, athletic jackets associated with gangs, certain colors for the same reason, etc.

But what’s next? Will an Orthodox Jewish student be prohibited from wearing a yarmulke because extremist West Bank Israeli settlers vandalized a mosque? Will that exchange student from Jordan be forced to remove her veil because extremists in her faith fly planes into buildings and regularly and indiscriminately engage in explosive mass murder of civilians?

I agree with Omaha Catholic Archdiocese Chancellor Rev. Joseph Taphorn’s argument that no one should have to give up symbolic expressions of faith simply because others misuse them.

The American Civil Liberties Union, so often on the other side of faith-in-the-public-square debates, also sees the policy as going too far: it just plain violates free speech and religious practice rights.