Far more than a chance to gorge on turkey, stuffing, yams, pies, hams and mashed potatoes and gravy, Thanksgiving is a time for reflection, and the gift of perspective.

We tend to look to the so-called “first Thanksgiving” as that 1621 get-together of Pilgrims and Native Americans at Plymouth. Really, though, it was a harvest celebration carried over from similar traditions in the Old World. And, it coincided with the corn harvest feast long practice by the Wampanoag Indians. The latter had taught the Pilgrims how to grow corn, and had hit their own tribal stores to help the newcomers survive.

Getting together for what turned out to be three days of eating, dancing and cultural exchange seemed like the natural thing to do. Such feasts, usually in fall and harvest-related, but held irregularly and with varying levels of religious zeal mixed with the age-old human tendency to find any excuse to party down, continued here and there into the 1800s.

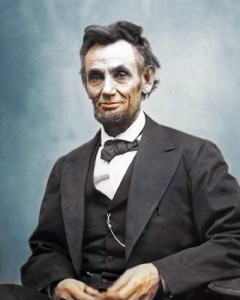

But the real, official Thanksgiving Day as a national observance came by presidential proclamation in 1863. Abraham Lincoln (at the time a newly committed Christian, by the way) ordered that the last Thursday of November be set aside as “a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens.” (Good grief; can you imagine the hue and cry from separationists and atheists if this was something new from the White House today?)

Be that as it may. It occurs to me that the day Lincoln issued this proclamation, Oct. 3, 1863, came not at the nation’s finest hour, not with the economy soaring and happiness ruling the land, but after a year of bloody battles with the Confederacy. Union armies had been defeated with heavy losses at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, and while Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had finally been halted at Gettysburg, the butcher’s bill had been a bloody wash: 51,000 casualties, or one-third of the soldiers on both sides who fought and died for three days.

Lee retired in order to dig in south of the Potomac River, battered but still full of fight; the war would rage on for another 22 months, and Lincoln would barely survive re-election in a war-weary North a year later.

Thanksgiving, indeed. Lincoln’s proclamation contains much humility and a strong appeal to perspective. There is a yearning for “the gracious gifts of the Most High God who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.”

Lincoln told a nation bitterly divided and awash in the cruelty of war and deprivation that there was still no better time for “humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience” and to “commend to his tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers” of war. The President concluded by praying for “the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it . . . to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union.”

Today, our nation again is at war, weary of the losses thousands of young lives. Our economy is in recession and our leaders deadlocked over how to restore our fortunes. We are polarized over half a dozen issues, and fearful of a dark, uncertain future.

President Obama could, with very little editing, re-issue Lincoln’s Thanksgiving proclamation today for us all to consider on Thanksgiving 2011.

We have no shortage of widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers today.

And God knows, we are in need of healing, tranquility and union.