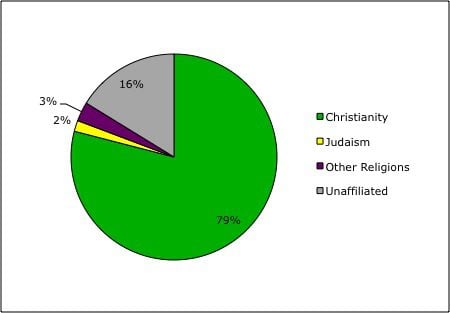

In my last post, I presented a visual pie chart graphically displaying the relative sizes of the major religions that are currently predominant within the United States. I also compared and contrasted that U.S. religious pie chart with a second pie chart, presented in preceding blog entries, which graphically displayed the relative proportions of the major world religions as they currently exist upon the broader, global scene (a global religious pie chart, depicting the wider worldwide religious landscape).

Within the U.S. today, the domestic religious landscape looks something like this:

In this post, I’d like to further refine that U.S. religious pie chart, by breaking down most of its somewhat sweeping broad and general categories into more narrowly precise subcategories.

I say “broad and general” categories, because labels such as “Christianity,” “Other Religions,” and “Unaffiliated” each actually cover quite a bit of diversity within themselves.

After all, “Christianity” alone covers such diverse Christian subgroups as Protestants, Catholics, Mormons (arguments to the contrary notwithstanding, at least for polling purposes), and others.

Likewise, “Other Religions” also lumps together quite a lot of highly diverse ground, including Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and of course many, many others.

Finally, the broad category of “Unaffiliated” can be broken down into at least three distinct subgroups: atheists (those who either flatly deny the existence of God, or else merely hold no personal belief in God), agnostics (those who either proclaim personal uncertainty regarding the existence of God, or else flatly assert that such certainty is impossible either way), and those who may hold at least some religious, spiritual, or “metaphysical” views, but who simply do not specifically affiliate themselves with any one particular formally established religion (e.g., “spiritual but not religious” folks, New Agers, independent seekers, freelance mystics, and similar variants).

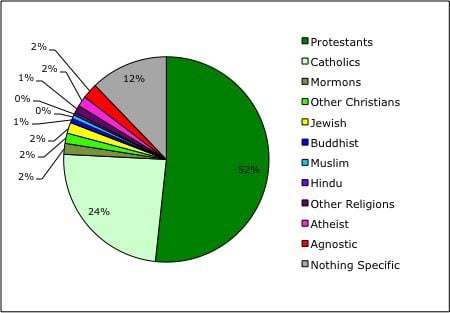

Here’s how a more narrowly refined version of that same U.S. religious pie chart breaks down the domestic religious and spiritual landscape:

Perhaps the first thing to note is the fact that American Christianity is nearly one-third Catholic. About 25% of the total U.S. population (Christian and non-Christian alike) is Catholic. The other two-thirds of Christians in America are almost entirely Protestant (amounting to about half of the total U.S. population). So, Protestants outnumber Catholics in America by about two to one.

However, that big Protestant half of the U.S. religious pie is by no means homogenous. The term “Protestant” itself actually covers a lot of very diverse Christian ground, ranging from mainline Protestant denominations (Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians) to Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh-Day Adventists, from Amish and Mennonites to evangelicals, Pentecostals, and “non-denominationals.”

If that big Christian half of the pie were further subdivided into individual slices for all of those diverse subgroups, it would end up a pretty splintered-looking half. That Catholic quarter of the pie would, in fact, be bigger than any one of the resulting individual Protestant slices, on its own. (The Baptist slice would be the next biggest slice, after the Catholic one; the Southern Baptists are the nation’s single largest Protestant denomination.)

In addition to Protestants and Catholics, the Christian section of the pie (comprising about 80% of the entire U.S. pie) also includes two relatively small slices representing Mormons on the one hand, and on the other hand literally “everything else” — any other religions in America that fall within the broad umbrella of “Christian.”

The Jewish slice of the pie isn’t much bigger than either of those last two slices, and again this often comes as a surprise to people who may be unfamiliar with religious demographics. Many seem to expect the domestic (as well as the international) Jewish population to be considerably larger than it actually is, given their profound prominence throughout Western religious history.

As with the Protestant slice, the Jewish slice of the pie could be further subdivided to illustrate the relative sizes of Judaism’s various sects or branches. However, the resulting slices — individually representing Orthodox Judaism, Conservative Judaism, Reform Judaism, etc. — would be very slender indeed.

The next broad category contains within itself all remaining formally established religions in America other than Judaism and Christianity. As the chart makes clear, this covers a lot of very diverse religious ground (Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu, and finally “everything else”); but again, each of these several diverse slices is pretty thin, relative to the entire pie as a whole.

Atheists and agnostics each comprise fairly slender slices of their own. Interestingly, the third biggest single slice in the entire pie (after the huge Protestant and Catholic slices) is the one which contains the “spiritual but not religious” or “nothing specific” crowd — not irreligious outright, yet religiously “unaffiliated,” as it were. This single large slice also masks, of course, an immense amount of diversity of its own, since individual personal forms of spirituality, or of “unchurched” religious or metaphysical beliefs, can run a seemingly near-infinite gamut.

This final slice of the pie may well represent “rugged American individualism,” or “the American spirit of self-directed independence,” as currently applied to the sphere of religion and spirituality by a great many contemporary average Americans today.