Much like every other major religion, Hinduism is not one thing, but many — not homogeneous and monolithic, but internally diverse and highly variegated. Within the Hindu religious tradition, God or the Divine can be imaged, visualized, conceptualized or comprehended in a number of alternative ways.

Among the most popular Hindu forms, manifestations, personalities, or “versions” of God are Vishnu, Shiva, and Shakti. And in each case, God — be he Vishnu or Shiva (or be she Durga or Kali) — is at the center of a rich and unique mythology of stories and songs, of art and ritual. Often, the Supreme Lord is further surrounded with an extended family of divine spouses, consorts, offspring, and assorted other related gods and demigods.

However, these Hindu gods are not jealous gods, commanding exclusive allegiance or sole worship. Hindus who primarily worship Vishnu don’t think that Hindus who instead worship Shiva are erroneously worshipping a “false” god, or vice versa. Neither do Vaishnavites (Hindus who worship Vishnu as the Supreme God) nor Shaivites (Hindus who worship Shiva as God) believe that Shaktas (Hindus who worship God as Goddess, as Devi or the Divine Feminine, in any of a number of alternate popular female forms such as Durga or Kali) are mistakenly worshipping the “wrong” deity.

Each recognizes and accepts that the other is merely worshipping the same supreme divine Reality in a different way, or through a different set of theological “lenses.” For Hindus, God has many names.

One branch within Hinduism — whose adherents are known as Smartas — generally worship several such deities (or forms of Deity) simultaneously. They may also choose to focus their devotions upon one specific deity in particular, with such choice being completely up to individual preference. Everyone is free to worship the Divine in whichever traditional Hindu form one most “resonates” with.

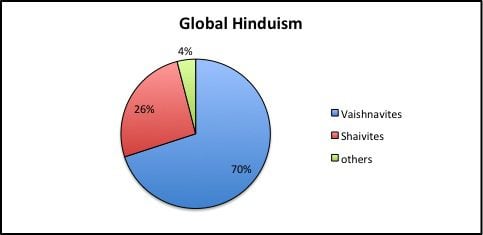

Population statistics on the total numbers of adherents comprising each of the four major Hindu wings or branches — Vaishnavite, Shaivite, Shakta, and Smarta — are difficult to come by, and probably somewhat imprecise. However, one source estimates the approximate breakdown as follows:

Vaishnavites (devotees of Vishnu) may account for as many as 70% of the total Hindu populace; Shaivites (devotees of Shiva) for perhaps roughly 26%; and Shaktas, Smartas, and others for about 4%.

All of this worship of multiple gods and goddesses (and their extended families and entourages) may sound, to Western religious ears anyway, like the most blatant form of polytheism. One traditional source even puts the total number of Hindu gods at something on the order of 330 million! And yet, many if not most Hindus affirm that all of these various gods are in reality just so many aspects, facets, forms, manifestations, modes, or alternative “public images” of a single Supreme God.

If that affirmation of monotheism in the face of such seeming polytheism sounds inconsistent, incoherent, or self-contradictory, consider first how the world’s largest religion (a Western monotheism, at that) makes much the same sort of theological claim. Christianity is staunchly and insistently monotheistic, in that it affirms the existence of one and only one God; and yet, in the same breath, it also affirms the effective reality of what sounds very much like three separate deities — the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, said to represent three distinct Persons.

To uncompromisingly monotheistic Jews and Muslims, this Trinity business just sounds like sheer “tri-theism.” But Christian theology maintains that there is actually a deeper and overarching unity behind that seeming diversity: God is One, even while also in some sense Three. It’s all chalked up to being a divine Mystery, and as such simply accepted on faith.

But if Christian theology can insist that the three divine Persons of its holy Trinity are, in some sense, ultimately one and the same God, then why can’t Hindu theology also affirm that its 330 million gods are likewise actually all the selfsame Supreme Reality? Is a Three-In-One type of God intrinsically more logical or believable than a 330-Million-In-One type of God?

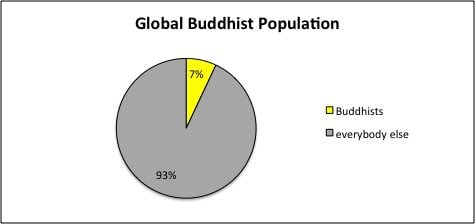

It’s also worth mentioning, in conclusion, that the characteristic Hindu tolerance of multiple gods — understood as multiple ways of conceptualizing and worshipping the same Divine Reality — is extended by Hindus well beyond Hinduism itself. Other religions are likewise viewed as constituting alternative, yet also perfectly legitimate and equally valid, spiritual pathways. According to this broadly inclusive Hindu view, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Taoism and the rest are themselves all just so many other diverse paths — a plurality of paths that all actually ascend the same mountain.

Or, as the Rig Veda (Hinduism’s oldest holy scripture) puts it, “Truth is One; sages call it many names.”