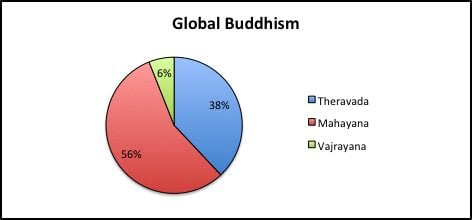

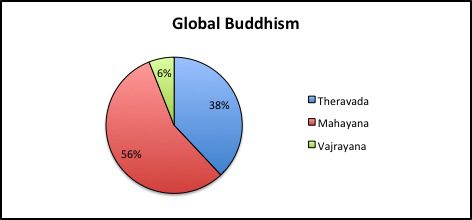

The Buddhist world subdivides into three major branches: Theravada, Mayahana, and Vajrayana.

In my previous post, I provided a short thumbnail sketch of what Theravada Buddhists believe and practice. Now, we’ll finish painting the broad Buddhist picture with brief portraits of the other two major Buddhist branches.

Mahayana (“Greater Vehicle”) Buddhism is predominant throughout East Asia: China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, and Vietnam. Mahayana appeared on the scene several centuries after the time of Gautama Buddha; while it is therefore younger than Theravada, it is also larger than Theravada (possibly much larger, depending upon whose statistics you accept as being the most accurate).

The very term “Mahayana” (maha = “great,” “large”; yana = “vehicle,” “conveyance”) suggests that Buddhism is perhaps best viewed as being a kind of vehicle, a raft or boat especially designed to carry or convey individuals to the “other shore” of nirvana, with the added emphasis that Mahayana offers a much bigger such raft or vehicle — one with vastly greater carrying capacity — and so is able to convey far more individuals to nirvana than the narrower (because more demanding) path of Theravada, with its heavy monastic emphasis.

Mahayana contains a number of additional new elements which are not characteristic of Theravada belief and practice. Many of these new Mahayana developments (seen not as doubtful “innovations” but rather as fresher and deeper insights, or as previously obscure teachings which were nevertheless present all along) serve to immensely improve and maximize accessibility to nirvana, such that layfolk as well as monks have a realistic shot at attaining nirvana during the present life. Such expanded “equal opportunity” access to the ultimate Buddhist religious goal in effect serves to greatly “level the playing field,” by offering a rich diversity of Mahayana sects and a multiplicity of viable and effective spiritual paths leading nirvana-ward that anyone and everyone may pursue.

For instance, whereas for Theravada the Buddha was just a man who discovered the way to nirvana, and who now serves as an example or role model for others to emulate and model themselves after as they work on progressing along their own path to enlightenment and release from rebirth (achieved by their own efforts, and without outside supernatural aid), Mahayana introduced an entire pantheon of enlightened cosmic buddhas (Gautama was not the only Buddha, after all, and he and all the other Buddhas are more than merely human), along with a constellation of celestial compassionate bodhisattvas (saint-like enlightened beings who compassionately postpone their own final eternal bliss in order to remain available to aid others, who are still slowly struggling along the path to nirvana).

In contrast to the Theravada view, Mahayana affirms that genuinely effective “outside help” in the form of supernatural spiritual aid is available, after all. Bodhisattvas freely share their own overabundances of excess good karma with any suffering sentient beings who might ask in prayer to receive it. Buddhas make available heavenly afterlife realms into which the faithful may be reborn (not exactly nirvana — perhaps — but the next best thing at the very least, and an optimal platform from which nirvana can then be far more easily attained), simply by having faith in the Buddha’s promise and by repeatedly chanting, in faith, the name of the Buddha in question. Some Buddhists even believe that the sacred power inherent within certain key Buddhist scriptures is so potent that it may be effectively tapped into merely by repeatedly chanting the name of the scripture in question; doing so can generate good karma, and even contribute directly to one’s unfolding spiritual growth and eventual enlightenment. And for those with a taste and the temperament for intensive meditation, there are also various sects of Zen (literally “meditation”) Buddhism.

Mahayana thus offers a broad range of diverse sectarian paths and practices, all capable of carrying everyone — monks and laymen, alike — toward nirvana.

Vajrayana (“Diamond Vehicle”) Buddhism is the predominant form of Buddhism in Central Asia, found primarily in Bhutan, Mongolia, and Tibet (in a characteristic form known simply as “Tibetan Buddhism,” whose best-known spokesman is of course the Dalai Lama). Yet another form of Vajrayana Buddhism can also be found in Japan, practiced by a sect known as Shingon (“True Word”) Buddhism.

Some view Vajrayana as merely a subset of Mahayana. Others view it as a distinctive third branch of Buddhism all its own. In either case, a distinguishing feature of Vajrayana is its employment of unique esoteric teachings and practices, which are deployed as additional tools and techniques helping to expedite one’s progress along the path leading to buddhahood and nirvana.

Such tools include the use of special spiritually empowering initiations and other rituals, advanced personal training under the watchful eyes of expert gurus and lamas, special esoteric forms of yoga, and the judicious employment of mantras (words and syllables of intrinsic spiritual power), mudras (symbolic hand gestures conveying spiritual power), and mandalas (complex symbolic, often geometric visual designs used for meditative and other purposes), all as tools designed to help evoke spiritual transformation and accelerate spiritual awakening.

As should be abundantly clear by now, Buddhism is not one thing, but many. Like other religions, it’s diverse, complex, multifaceted, and complicated.