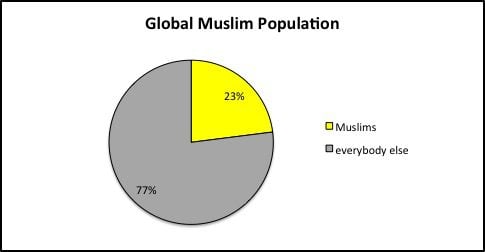

With approximately 1.6 billion followers (about 23% of the total global human population), Islam currently ranks as the second largest religion in the world.

But Islam, like the rest of the world’s religions, is not one thing, but many. Islam is not homogeneous and monolithic, but variegated and diverse.

For one thing, Islam, like other major religions, itself formally subdivides into a number of divergent wings, branches, and sects. Just as there are Orthodox Jews, Conservative Jews, and Reform Jews, and just as there are Roman Catholic Christians, and Eastern Orthodox Christians, and all manner of Protestant Christians (Baptists, Methodists, Lutherans, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Amish, Mennonites, Quakers, Seventh-Day Adventists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons, Pentecostals, non-denominationals, etc.), so likewise there are also different kinds of Muslims, as well.

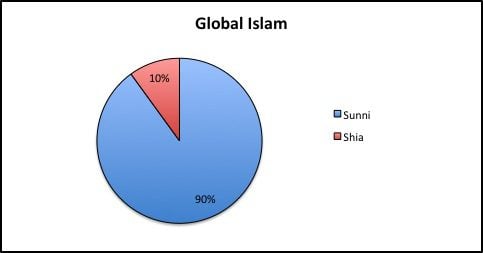

The major doctrinal schism or division within Islam is its split into two primary wings, branches, or “denominations”: the Sunni majority (80% to 90% of Muslims are Sunni Muslims), and the Shi’a minority (10% to 20% of Muslims are Shi’ite Muslims). Shi’ites are a minority throughout most of the Muslim world, except within the four nations wherein they constitute a majority of the population: Iran (which is 90-95% Shi’a), Azerbaijan (85%), Bahrain (65%), and Iraq (60-65%).

Sunnis (“traditionalists”) adhere to the Sunnah (“path,” “tradition”), the large body of preserved traditions attributed to Muhammad illustrating the ideal “straight path” or faithful Muslim way of life as demonstrated by the Prophet’s own example, along with how best to understand, interpret, and implement the Quran in daily life. Sunnis further believe that since Muhammad himself appointed no successor to lead the Islamic community after his death, such successive leaders — known as caliphs (“deputies,” “representatives”) — should be selected by the community itself.

Shi’ites (“partisans”), by contrast, believe that Muhammad appointed as his successor his own cousin and son-in-law, Ali (hence Shi’ites are “partisans of Ali”). They further believe that all subsequent heads of the Islamic community — referred to in Shi’ism as Imams (“leaders,” “guides”) — should be descendants of Muhammad and Ali, rather than unrelated appointees, who would thereby preside by divine right and enjoy almost pope-like infallibility and authority.

Disputes over the legitimacy of the exact line of successive Imams down through subsequent generations has led to further splits and schisms within Shi’a Islam. The Shi’ite community today is now subdivided into such sects as the “Twelvers” (so called because they recognize as legitimate a specific terminal line of twelve hereditary Imams), the “Fivers” (who recognize a shorter line of only five such Imams), and the “Seveners” (who recognize a line of seven such Imams).

Yet another variant form of Islam is known as Sufism. However, Sufism constitutes not a denomination or sect per se, but a pan-denominational, pan-Islamic mystical movement. Sufis are the mystics of Islam, practicing their ascetic, meditative, and other sorts of intensive spiritual disciplines in a quest to attain states of mystical union with the Divine. Individual Sufis may be either Sunnis or Shi’ites; Sufi groups may be Sunni, Shi’a, or mixed. Sufi mysticism crosses denominational and sectarian lines.

(To be continued, and concluded, in Part Three.)