Buddhism, like the other major religions of the world (such as Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism), is by no means universally homogeneous and uniform in content, but is instead heterogeneous, highly variegated, and internally diverse.

In other words, not all Buddhists believe the same exact things, or practice in exactly the same ways (no more so than all Christians, or all Jews, or all Muslims, or all Hindus believe and practice identically).

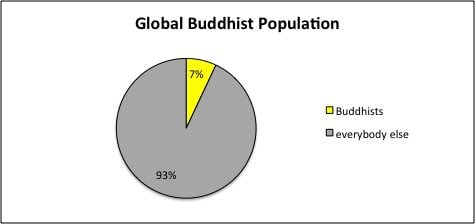

The fourth largest major world religion (after Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism, in descending order), the actual total Buddhist population is tricky to precisely pin down (for reasons mentioned in my previous blog entry), but perhaps somewhere around 500 million (about 7% of the world’s population) is not too far from the mark.

Buddhism is unusual among the world’s religions in that it acknowledges neither the existence of a creator God nor the existence of an eternal soul. For these reasons, people sometimes suggest that Buddhism isn’t really a religion, per se, but just a spiritual philosophy, or even a form of spiritual psychology.

But why should the definition of “religion” be limited to just those forms of spiritual belief and practice that entail God (or gods) and a soul?

Additionally, within Buddhism can be found all of the various other elements commonly associated with religions: myths, rituals, ethics, scriptures, priests, temples, monks, monasteries, meditation, prayer, chanting, and so forth.

And if religion in whatever form is ultimately a search for transcendence and a means of ultimate transformation, then surely Buddhism qualifies as religion.

Buddhists may not pray to a creator God, or believe that they have an eternal soul, or aspire to an eternal afterlife in a heavenly paradise; but they do believe in karma and rebirth, they venerate the Buddha as a mystically enlightened human being who showed the way to nirvana, and they aspire to follow in the Buddha’s footsteps in order to someday attain the eternal bliss of nirvana for themselves (even if it takes them many lifetimes to do so).

Some Buddhists even believe in an entire pantheon of enlightened cosmic buddhas (additional buddhas besides “the” Buddha) and compassionate celestial bodhisattvas (saintlike beings who postpone their own nirvana for the sake of remaining available to aid others who are still suffering and struggling toward nirvana and need outside assistance to attain it), to whom veneration and prayers are directed.

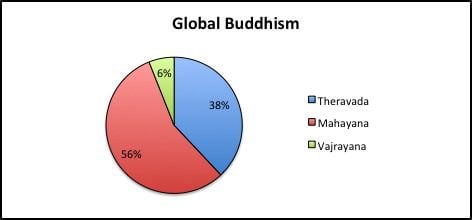

So, just how does this whole wide world of Buddhism break down, or subdivide, into its own multiple major branches, sects and schools, or “Buddhist denominations”?

Well, for a start, probably something about like this:

The Buddhist world subdivides, first of all, into three major branches: Theravada, Mayahana, and Vajrayana.

How do these three main branches differ from one another? Stay tuned!

(To be continued, in Part Three.)