Gary Zukav, who wrote “The Dancing Wu Li Masters,” has this famous aphorism:

Acceptance without proof is the fundamental characteristic of Western religion, rejection without proof is the fundamental characteristic of Western science.

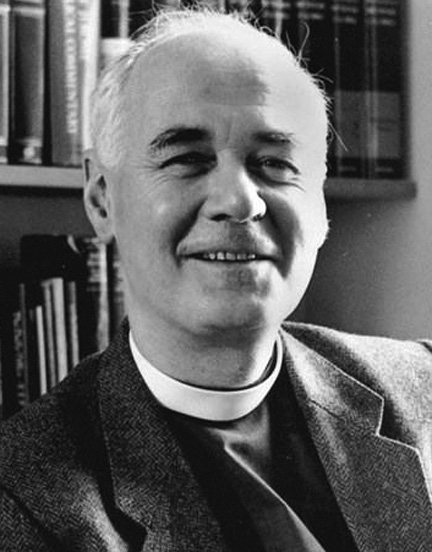

I thought of it when I read the following passage from Krista Tippett’s interview with John Polkinghorne, the particle physicist and theologian:

Ms. Tippett: You also talked about how, in the same way that we take seriously the insights of science, we need to listen to the words of poets and to the insights of saints and mystics, and to hearing that also in that context.

Mr. Polkinghorne: Absolutely. Yes. I think reality is very rich, many-layered, and science, in a sense, explores only one layer of the world. It treats the world as an object, something you can put to the test, pull apart and find out what it’s made of. And, of course, that’s a very interesting thing to do, and you learn some important things that way. But we know that there are whole realms of human experience where, first of all, testing has to give way to trusting. That’s true in human relationships. If I’m always setting little traps to see if you’re my friend, I’ll destroy the possibility of friendship between us.

And also where we have to treat things in their wholeness, in their totality. I mean, a beautiful painting, a chemist could take that beautiful painting, could analyze every scrap of paint on the canvas, tell you what its chemical composition was, would, incidentally, destroy the painting by doing that, but would have missed the point of the painting, because that’s something you can only encounter in its totality. So we need complementary ways of looking at the world. Bits and pieces, for sure, that’s a worthwhile thing to do, but not the whole story.

Polkinghorne goes on to discuss the mystery of of how light could be both wave and particle. Scientists observed that light had properties of both, but that appeared to be a contradiction:

[Polkinghorne:] And then the thing has a happy ending, I’m glad to say, back in my old University of Cambridge where Paul Dirac discovered something called quantum field theory. Now, a field is something that is spread out, and so it can be flappy. So it certainly has wave-like properties. But when you bring in quantum theory, it makes things come in packets. That’s the effect of quantum theory, it chops things up into little packets. And little packets look like little particles, and so a quantum field has both these sorts of properties. And if you ask it a wave-like question, it gives you a wave-like answer. You ask it a particle-like question, it gives you a particle-like answer. And you can’t ask both questions at the same time, which saves you from having, you know, a contradiction.

Ms. Tippett: OK. But you take both answers into account.

Mr. Polkinghorne: You take both answers into account. And the important thing I want to emphasize is that people had to cling on to taking both insights into account before they understood how they fitted together. We don’t make progress by chopping experience down to a size that fits into our current theories. We have to allow the way the world is to modify our understanding of the world. And, if you’re a Christian theologian, and you’re telling that sort of story that I’ve just told about light being both particle-like and wave-like, we know that the Christian story about Jesus Christ is that He is, of course, a human being but also, in some real sense, needs to be described in terms of divine language. And it’s the same sort of dilemma, if you like, and we’re not quite so clever, theologically, at finding the precise answer to that. But, again, we don’t make progress by denying our experience.

We don’t make progress by denying our experience. I like that. I’m intrigued too by the way Polkinghorne takes a real-life example of a fundamental scientific paradox and uses it to illuminate religious paradoxes. Christianity is full of them. How can the godhead be both three and one? How can the eternal, infinite God also be temporal and finite (this is the paradox of the Incarnation)? How can God be all-good and all-powerful, yet allow evil to exist? And so forth.

I’ve linked to the Polkinghorne interview of Krista’s “Speaking of Faith” website, but I read it last night in her new interview collection, “Einstein’s God,” which I highly recommend.