I’d said in the Ugly Churches post that calling a particular church “regrettable” isn’t meant as a judgment on the religion itself or the parishioners who worship there, but only on the architecture itself. But it’s true that architecture, especially church architecture, should express the values and beliefs of those who use the building for their gatherings. It’s generally true that architecture, like all forms of art, expresses values, spiritual and otherwise, and shapes the way those who live with and among those buildings see the world.

With that in mind, please take a look at Michael Totten’s fascinating report from Romania, which was passed along by a Dallas reader. Totten writes about how communism brutalized the country, and how it still has a long way to go to recover. What the dictator Nicolae Ceaucescu did to Bucharest, by destroying so much of its traditional architecture in his quest to create the communist New Man, can never be repaired. Totten:

Ceausescu’s communist urban planners chopped up Bucharest with a meat axe.

They pulled down most of the classical buildings that once made the city aesthetically pleasing, then they put up a bunch of crap in their place. The streets are too wide. Buildings don’t match, and sometimes there is far too much space between them. There isn’t much coherent fabric or feel to most of the city, even in most of the old city center. It is very nearly an antithesis of Paris.

The brilliant Anthony Daniels, who now writes under the pen name Theodore Dalrymple, loathes ghastly brutalist architecture as much as I do. He properly blames the Swiss architect Le Corbusier and his baleful influence for wrecking so many once beautiful cities like Bucharest and even marring cities like London.

“Le Corbusier was to architecture what Pol Pot was to social reform,” Daniels recently wrote in City Journal. “In one sense, he had less excuse for his activities than Pol Pot: for unlike the Cambodian, he possessed great talent, even genius. Unfortunately, he turned his gifts to destructive ends, and it is no coincidence that he willingly served both Stalin and Vichy.” Le Corbusier, he says, “was the enemy of mankind” and “does not belong so much to the history of architecture as to that of totalitarianism.”

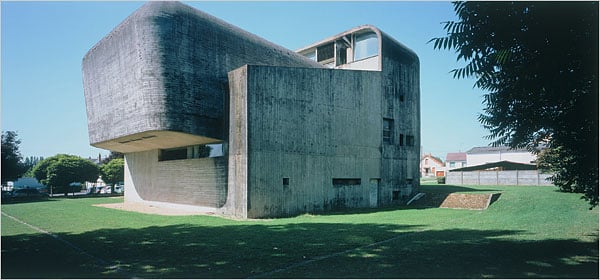

The grotesque modern architect once described a house as “a machine for living in” and is still scandalously lionized by many professionals in the field even today. (Do such people stay in the asteroid belt of tower blocks in the suburbs of Paris when they visit on holiday, or do they prefer the beautiful parts of the city such as the Latin Quarter like normal human beings do?)

Read Totten’s report, if only to see his photographs of modern Bucharest’s hideousness. The people of Bucharest are going to have a more difficult time recovering from the Ceaucescu tyranny than will the people of Romanian towns whose traditioanl architecture was left alone by the communists (Totten has some lovely photos of those places). And do check out Theodore Dalrymple’s meditation on the baleful influence of the madman Le Corbusier. Here, Dalrymple recalls meeting with two women at a recent exhibition dedicated to celebrating Le Corbu’s legacy (read on, past the jump — there’s a point I want to make here, but I don’t want to make this entry too long on the front page):

At the exhibition, I fell to talking with two elegantly coiffed ladies of the kind who spend their afternoons in exhibitions. “Marvelous, don’t you think?” one said to me, to which I replied: “Monstrous.” Both opened their eyes wide, as if I had denied Allah’s existence in Mecca. If most architects revered Le Corbusier, who were we laymen, the mere human backdrop to his buildings, who know nothing of the problems of building construction, to criticize him? Warming to my theme, I spoke of the horrors of Le Corbusier’s favorite material, reinforced concrete, which does not age gracefully but instead crumbles, stains, and decays. A single one of his buildings, or one inspired by him, could ruin the harmony of an entire townscape, I insisted. A Corbusian building is incompatible with anything except itself.

The two ladies mentioned that they lived in a mainly eighteenth-century part of the city whose appearance and social atmosphere had been comprehensively wrecked by two massive concrete towers. The towers confronted them daily with their own impotence to do anything about the situation, making them sad as well as angry. “And who do you suppose was the inspiration for the towers?” I asked. “Yes, I see what you mean,” one of them said, as if the connection were a difficult and even dangerous one to make.

This encapsulates one of the great mysteries of our era: why did ordinary people capitulate to this insanity? The poor Romanians, and other subject peoples who lived under communist totalitarianism, never had a choice. But we in the West did. We let them get away with so much inhumanity — and still do, in many cases and places. In both East and West, it seems, all that was necessary to work this wickedness was to capture the imagination of the elites. But at least the Romanians and others had no chance to fight back. What’s our excuse?