I read this Peggy Orenstein column from the Sunday NYT Magazine and got angry in a familiar way. She’s deploring the cultural trend of the early sexualization of girls. Here’s how her piece begins:

Last month, over the course of one workday, six friends sent me a link to the same video along with messages that said, “Have you seen this?” I had, but I clicked it each time anyway. I just couldn’t stop myself. The clip showed a troupe of 8- and 9-year-old Los Angeles girls in a national dance contest. Wearing outfits that would make a stripper blush, they pumped it and bumped it to the Beyoncé hit “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It).” The girls were spectacular dancers, able to twirl on one foot while extending the other into a perfect standing split. But I doubt that two million people had tuned in simply to admire their arabesques. As with TV phenomena like “Toddlers and Tiaras,” the compulsion to watch was like the impulse to rubberneck at an accident, but in this case the scene was a 12-car pileup of early sexualization.

Orenstein recognizes that the eroticization of children is a Bad Thing, because, in her view, it’s screwing up the heads of females:

I might give the phenomenon a pass if it turned out that, once they were older, little girls who play-acted at sexy were more comfortable in their skins or more confident in their sexual relationships, if they asked more of their partners or enjoyed greater pleasure. But evidence is to the contrary. In his book, “The Triple Bind: Saving Our Teenage Girls From Today’s Pressures,” Stephen Hinshaw, chairman of the psychology department at the University of California, Berkeley, explains that sexualizing little girls — whether through images, music or play — actually undermines healthy sexuality rather than promoting it. Those bootylicious grade-schoolers in the dance troupe presumably don’t understand the meaning of their motions (and thank goodness for it), but, precisely because of that, they don’t connect — and may never learn to connect — sexy attitude to erotic feelings.

Wow, who could have figured that would happen if we tore down fences in the name of sexual revolution? Who could have possible foreseen that the sexual revolution would end up victimizing girls? Here’s the graf that cheesed me off, though:

I find myself improbably nostalgic for the late 1970s, when I came of age. In many ways, it was a time when girls were less free than they are today: fewer of us competed on the sports field, raised our hands during math class or graduated from college. No one spoke the word “vagina,” whether in a monologue or not. And there was that Farrah flip to contend with. Yet in that oh-so-brief window between the advent of the pill and the fear of AIDS, when abortion was both legal and accessible to teenagers, there was — at least for some of us — a kind of Our Bodies, Ourselves optimism about sex. Young women felt an imperative, a political duty, to understand their desire and responses, to explore their own pleasure, to recognize sexuality as something rising from within. And young men — at least some of them — seemed eager to take the journey with us, to rewrite the rules of masculinity so they would prize mutuality over conquest.

Ross Douthat has observed a similar nostalgia emerging in Caitlin Flanagan, who is about the same age as Peggy Orenstein. Flanagan often writes about the negative consequences of the sexual revolution for girls, but she doesn’t do so in a typically conservative way. Ross:

Flanagan is an instinctive social conservative, but intellectually she’s torn between these instincts and a nostalgia for 1960s social liberalism, with its vision of a cultural landscape in which premarital sex would be largely destigmatized, perfectly safe, and intensely romantic all at once.

But as Ross says, and as both Orenstein and Flanagan don’t appear to realize, that world never existed. Human beings being what we are, that world cannot exist. (I bet Camille Paglia would lay into both Flanagan and Orenstein on this stuff like a she-wolf). I read Orenstein’s bit about being nostalgic for this idealized past in the same way I would read a gloomy, financially strapped Wall Street banker reminiscing about those glory days of the early Reagan years, when it was possible to believe that turning the market loose to work its magic would bring about a kind of utopia.

How were we supposed to know? is such a lame, lame excuse.

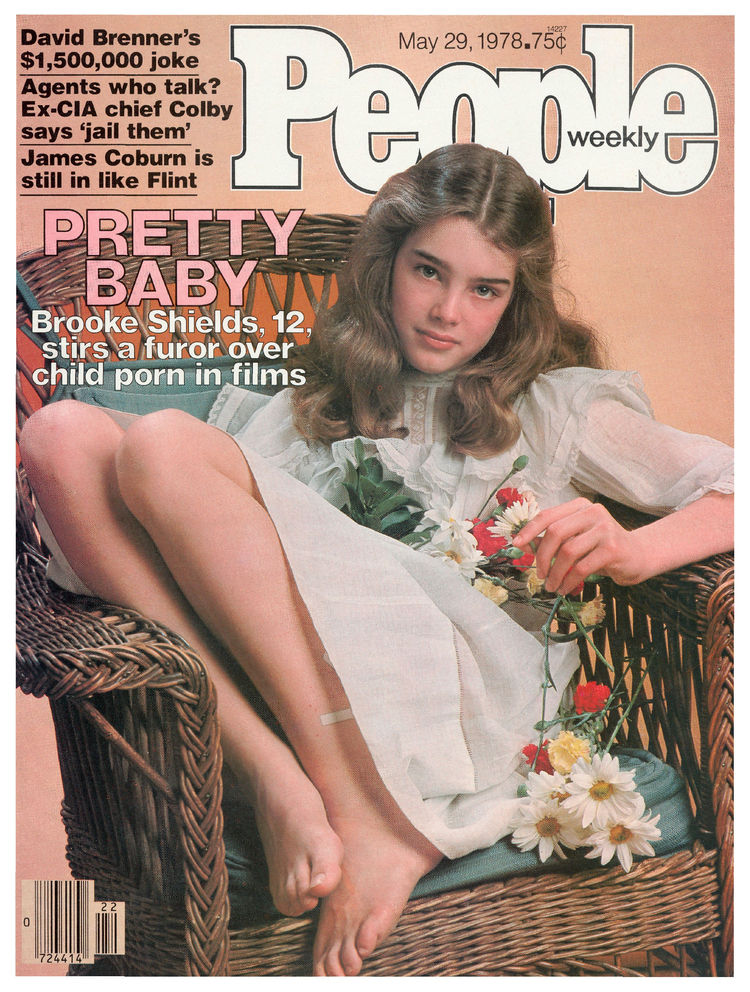

I remember when I was a kid, there was this huge, huge controversy over director Louis Malle presenting 12-year-old Brooke Shields as a child prostitute in “Pretty Baby.” The controversy centered over nude scenes involving Shields. People were really shocked back then. That was forever ago.