So says David Brooks in his column today. Excerpt:

There used to be theories that deep down narcissists feel unworthy, but recent research doesn’t support this. Instead, it seems, the narcissist’s self-directed passion is deep and sincere.

His self-love is his most precious possession. It is the holy center of all that is sacred and right. He is hypersensitive about anybody who might splatter or disregard his greatness. If someone treats him slightingly, he perceives that as a deliberate and heinous attack. If someone threatens his reputation, he regards this as an act of blasphemy. He feels justified in punishing the attacker for this moral outrage.

And because he plays by different rules, and because so much is at stake, he can be uninhibited in response. Everyone gets angry when they feel their self-worth is threatened, but for the narcissist, revenge is a holy cause and a moral obligation, demanding overwhelming force.

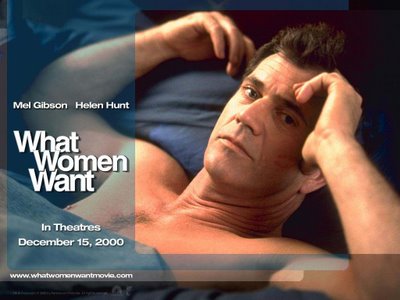

Mel Gibson seems to fit the narcissist model to an eerie degree. The recordings that purport to show him unloading on his ex-lover, Oksana Grigorieva, make for painful listening, and are only worthy of attention because these days it pays to be a student of excessive self-esteem, if only to understand the world around.

Leaving Gibson aside, Brooks’s description of the narcissistic personality describes the political and cultural atmosphere we’re living in today. Argue for something that violates someone’s self-esteem, and watch them explode in righteous anger. How dare you tell them they can’t have what they want! When I heard some of Mel Gibson’s recordings in which he hysterically (verbally) attacked his ex-girlfriend, I heard the voice of various people who have e-mailed me over the years, or who have posted on this blog. I hear the voice of people who call talk radio, or who host talk radio shows. I hear the voice of people who go on other websites to vent about the unregenerate evil of the Other, and who tell themselves it’s okay to do whatever one likes to destroy the enemy, because the very existence of people who deny our conception of ourselves is intolerable. I hear the voice of people who believe they have the right and the obligation to deny and radically reshape ancient institutions and teachings, because they will submit to no teaching, discipline or authority that challenges their sense of themselves (can there be a more narcissistic statement than ”

Which brings me to the most fundamental rule of my Catholicism — nobody gets to tell me that I’m not a Catholic”?). I hear the voice of angry people who believe any crazy thing that fulfills them emotionally, satisfied that they know the Truth, because they feel the truth.

The modern narcissist is not a minority, either. Brooks:

In their book, “The Narcissism Epidemic,” Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell cite data to suggest that at least since the 1970s, we have suffered from national self-esteem inflation. They cite my favorite piece of sociological data: In 1950, thousands of teenagers were asked if they considered themselves an “important person.” Twelve percent said yes. In the late 1980s, another few thousand were asked. This time, 80 percent of girls and 77 percent of boys said yes.

That doesn’t make them narcissists in the Gibson mold, but it does suggest that we’ve entered an era where self-branding is on the ascent and the culture of self-effacement is on the decline.

This is what you get when you have a culture built on emotivism, which is the philosophical view that feelings determine the truthfulness of a proposition. And it has serious public consequences. Alasdair MacIntyre’s view on this is explicated here. Excerpts:

They are not trying to persuade others by reasoned argument, because a reasoned argument about morality would require a shared agreement on the good for human beings in the same way that reasoned arguments in the sciences rely on shared agreement about what counts as a scientific definition and a scientific practice. This agreement about the good for human beings does not exist in the modern world (in fact, the modern world is in many ways defined by its absence) and so any attempt at reasoned argument about morality or moral issues is doomed to fail. Other parties to the argument are fully aware that they are simply trying to gain the outcome they prefer using whatever methods happen to be the most effective. (Below there will be more discussion of these people; they are the ones who tend to be most successful as the modern world measures success.) Because we cannot agree on the premises of morality or what morality should aim at, we cannot agree about what counts as a reasoned argument, and since reasoned argument is impossible, all that remains for any individual is to attempt to manipulate other people’s emotions and attitudes to get them to comply with one’s own wishes.

MacIntyre claims that protest and indignation are hallmarks of public “debate” in the modern world. Since no one can ever win an argument – because there’s no agreement about how someone could “win” – anyone can resort to protesting; since no one can ever lose an argument – how can they, if no one can win? – anyone can become indignant if they don’t get their way. If no one can persuade anyone else to do what they want, then only coercion, whether open or hidden (for example, in the form of deception) remains. This is why, MacIntyre says, political arguments are not just interminable but extremely loud and angry, and why modern politics is simply a form of civil war.

More:

If we are to fully understand emotivism as a philosophical doctrine, MacIntyre says, we must understand what it would look like if it were socially embodied. That is, if we stipulate that nearly all the people in a given society subscribe to emotivism, what can we expect their society look like? How will they behave? It turns out, MacIntyre says, that such a society would look much like ours, and that (as has been said) we act as though we believe emotivism to be true. MacIntyre says that “the key to the social content of emotivism….is the fact that emotivism entails the obliteration of any genuine distinction between manipulative and non-manipulative social relations” (After Virtue 23). Each of us regards the other members of our society as means to ends of our own. Because I cannot persuade people, and because we cannot have any common good that is not purely temporary and based on our separate individual desires, there is no kind of social relationship left except for each of us trying to use the others to achieve our own selfish goals. Even for someone who did not want to live this way, the fact that others would be trying to gain power over them in order to manipulate them would mean that they would still need to seek as much power as they could simply to avoid being manipulated. It would also mean that each of them would need to manipulate others in ways that would make it more difficult or impossible for them to be manipulated in return. This is similar to the argument that animates a good deal of Hobbes’ Leviathan, where the constant battle for power over one another in a state of nature leads to a life that is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short, and eventually to the recognition of the need for a sovereign with absolute power – although this, of course, is not the solution MacIntyre advocates.

MacIntyre teaches that in such a social order, virtue is inverted, and seems like a weakness. Thus do we see humility as a dangerous stance to adopt, because it leaves one especially vulnerable to those who have no doubt whatsoever about the correctness and indeed the righteousness of their own position.