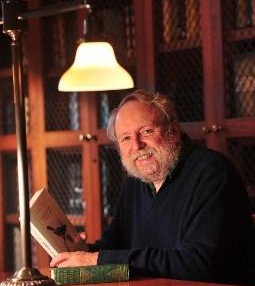

Every Monday, “Science and the Sacred” features an essay from one of

The BioLogos Foundation’s leaders: Karl Giberson and

Darrel Falk. Today’s entry was written by Karl Giberson.

Watching the discussion surrounding Francis Collins’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) appointment has been enlightening in so many ways. I was especially interested in the argument made by various critics, including Sam Harris in the New York Times, that someone with faith in God cannot be a good scientist because those two agendas are incompatible. This is not a new argument, of course, but the present occasion has brought it out of the archives and given it a bit of life.

The argument that belief in God interferes with doing good science is wrongheaded in so many ways.

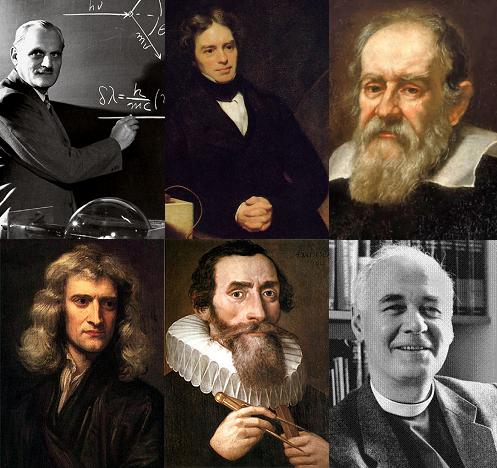

For starters, there is the historical argument. Galileo, Kepler, Newton, Faraday, and Compton were all religious believers and giants in the history of science. Their faith hardly prevented them from doing great science but, more than that, their faith in God actually contributed to original ways of thinking that spurred their scientific creativity.

Newton, for example, was the first person to articulate the concept of a universe. Prior to Newton, science–such as it was in those days–had been shaped by the worldview of pre-Christian Greece. The Greeks believed that reality had two distinct physical realms, one earthly and one heavenly. The earthly realm, extending to the moon, was a locus of decay, suffering, and imperfection. The heavenly realm was perfect and unchanging, with entirely different properties. Thinkers up to and including Galileo, who died the year Newton was born, accepted this Greek idea that the heavens were somehow “different.” (Galileo, for example, thought there was something called “circular inertia” that forced the planets to move in circular orbits, rather than Kepler’s ellipses.) Newton, however, rejected this notion and established to everyone’s satisfaction that the heavens and the earth were the same. His famous law is called universal gravitation because Newton believed the laws of nature were the same everywhere, even in those parts of the universe he could not see. Part of his inspiration for this reckless extrapolation from our solar system to the entire cosmos was his radical monotheism. Newton believed the entire universe was the creation of a single God and it would be incoherent for this universe to be a patchwork of regions with differing physical laws. A couple centuries later Michael Faraday would be similarly inspired to suggest the important idea of invisible, omnipresent electromagnetic fields, based partly on his belief that God was, in some sense, everywhere.

Not only have many great scientists found no conflict between their science and their faith, the latter has often enriched and even inspired the former.

An argument from the present confirms the argument from the past. I was privileged not long ago to meet Bill Phillips, who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1997 for his work on laser cooling. Phillips is an enthusiastic Christian, who even sings in his Methodist church choir. I am also happy to count John Polkinghorne among my personal friends. Polkinghorne, who held a chair of mathematical physics at Cambridge University for many years, is a distinguished particle physicist and now an Anglican priest. He helped develop the theory of quarks and has written extensively about science and religion. Now, if Phillips and Polkinghorne can do world-class science while believing in God, how can those things be incompatible?

There is something strange about atheists and agnostics who have made only modest contributions to science claiming that they can do good science because they don’t believe in God, but other scientists, far more distinguished than they are, cannot because their belief in God interferes. How does this argument work, exactly? This seems to me like lecturing at bumblebees that they cannot fly because we don’t understand the relevant aerodynamics. We can make this case as strongly as we want but, at the end of day, bumblebees still fly and we still wonder how.

And finally, I would challenge the claim that a religious scientist’s belief in God has no counterpart in the worldview of the agnostic or atheist scientist. E. O. Wilson, one of our greatest living scientists and the father of the field of evolutionary psychology, told Robert Wright in Three Scientists and Their Gods

that we need to “worship the evolutionary epic.” Let’s suppose that this actually happens and a new religion springs up in consequence, worshipping the evolutionary epic. Would a religion based on this practice be more or less conducive to good science than a traditional one, where we worship the creator of the world, rather than a process within that world?

Richard Dawkins wrote in The Ancestor’s Tale that he objects to supernatural beliefs because they “miserably fail to do justice to the sublime grandeur of the real world. They represent a narrowing-down from reality, an impoverishment of what the real world has to offer.” Would such a deeply rooted conviction that the world has a “sublime grandeur” interfere with scientific research? What if the fundamental character of the world is “mundane triviality”? Will Dawkins’s assumption to the contrary make it hard for him to discover that?

Our worldviews are shot through and through with idiosyncratic personal ideas about the nature of the world’s mysteries. Nowhere is this truer or more relevant than at the foundational level where we speculate about the fundamental character of the world. Here the questions are too deep for science and, as they say, people of good will can disagree. Is the world fundamentally rational? Mathematical physicists say “yes,” but many biologists, confronted with the higgledy-piggledy of natural history, are not so sure. Francis Crick, who shared the Nobel Prize for discovering the structure of DNA, reflected on this in his autobiography What Mad Pursuit. His movement from physics to biology required him to abandon the physicists’ intuition about nature “elegance and deep simplicity.”

The scientific community, like the gene pool of a species, is strengthened by the presence of diversity. Science, in fact, is a most congenial home for all manner of creative geniuses, including eccentrics like Einstein who snuck in the back door of science and became the face of genius without ever once combing his hair. Nothing would be any more damaging to science than to impose some peculiar requirement that only people who think a certain way can participate.

Karl Giberson is executive vice president of The BioLogos Foundation and director of the Forum on Faith and Science at Gordon College in Wenham, Mass.