Every Friday, “Science and the Sacred” features an essay

Every Friday, “Science and the Sacred” features an essay

from a guest voice in the science and religion dialogue. This week’s

guest entry was written by Dean Nelson, the founder and director of the journalism program at Point Loma Nazarene University in San Diego. He is writing a book with Karl Giberson about John Polkinghorne and the faith/science debate. Nelson’s most recent book is God Hides in Plain Sight: How to See the Sacred in a Chaotic World, published by Brazos Press. His website is www.deannelson.net.

John Polkinghorne, the world-famous physicist, got to church early on a recent Sunday.

It had been nearly twenty-five years since he had preached in this church and celebrated the Eucharist with its members. The church, in the Village of Blean, was built in the 1200s close to some Roman ruins and is just up the hill from the spectacular Cathedral at Canterbury. That Cathedral goes back to the sixth century, can hold thousands, has been the site of innumerable historical events, including the murder of one of its many famous Archbishops, Thomas Beckett, and stands out as the center of activity in that bustling medieval city. It was the destination of those travelers chronicled in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It costs about $10 (U.S.D.) to walk onto its grounds, and is visible for miles.

The Blean church is built on the edge of the village of about three thousand people, virtually out of sight except to those who pass on the public footpaths. It can hold about two hundred comfortably, but recently had several hundred more packed in for the funeral of a local soccer hero. There is no charge to walk in the unlocked doors during the week. It is a welcome shelter for those walking or biking on the nearby footpaths and for students at the University of Kent, about a mile away, who need a study break. Many of the visitors leave notes of thanks in the guest registry.

On this recent Sunday Polkinghorne set out the icon he had commissioned from Russian Orthodox monks of the patron saints of this church, two Arab brothers who converted to Christianity around 300 AD and then were martyred. Under the stained glass windows designed by a local artist, Polkinghorne prepared the table for the Eucharist. He looked up and admired the pipe organ, which for nearly one hundred years had been at the front of the church, but in recent years was moved to the rear, uncovering tombs from the 1600s. He arranged his papers at the pulpit, from where he would be preaching in less than an hour.

His arrival here in the mid-1980s had created a stir in the scientific community. Polkinghorne was at the top of the physics game at Cambridge University, being one of those credited with developing theories regarding quarks – the smallest known particles. Knighted by the Queen of England for his contributions to science and medical ethics, a member of the Royal Society (of which Isaac Newton was one of its first presidents), former president of Queens’ College at Cambridge University, author of more than 30 books, a 2002 Templeton Award winner, a debate opponent of atheist-scientists Richard Dawkins and Steven Weinberg–his reputation was vast, with students and colleagues desiring to be under his influence. So when he announced that he was leaving the science world at age 49 to attend seminary and enter the priesthood in the Anglican church, many of his colleagues told him he was committing intellectual suicide. Some wondered whether he was thinking clearly. Steven Weinberg wrote later that when he was in Polkinghorne’s kitchen and heard it straight from the physicist’s mouth, he nearly fell out of his chair.

For Polkinghorne, though, it wasn’t a matter of leaving the science world at all. It was more about satisfying a spiritual hunger that he had been wrestling with for years. Polkinghorne has never believed that science and religion were either/or. As a lifelong Anglican it had always been both/and.

“Science brackets out questions of meaning and purpose,” he told me. “Ask a scientist what music is – is it waves of sound? It’s also a timeless form of beauty. The scientist’s view has no persons in it.”

One of his goals as a priest was to help his congregation lose their fear of science – maybe even embrace it.

“I’m cross-eyed in how I approach things,” he said. “I look to the religious constituency to take science seriously. But also as a scientist I have motivation to my religious beliefs.” It was while he was the vicar of Blean that he wrote his famous book One World: The Interaction of Science and Theology. He wrote it in the mornings in his study in the vicarage, a five-minute walk from the church. In the afternoons he knocked on doors and visited with parishioners.

“If anyone was intimidated by having an intellectual giant like John come as our priest, that intimidation quickly dissipated,” said one parishioner. “His sermons were for everyone, and he truly loved everyone. I could always understand what he was saying. But I can’t get past the first page of any of his books.”

He was in Blean for only two and one-half years, before he was called back to Cambridge – first as Chaplain of Trinity College, and then president of Queens’ College.

The choir and the organist arrived to rehearse. Other members gathered – word had spread that their former famous priest was back in town, filling in for the vacationing vicar. In came the former mayor of Canterbury, whose term was during Polkinghorne’s time as Blean’s priest. Polkinghorne was her chaplain. There was the chaplain to the present Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Willams. There were the regular attendees, too. Some had first come to this church as a result of Polkinghorne’s knocking on their doors two decades ago engaging them in conversation about God. “You can do this yourself, you know,” he told one potential parishioner. “You can think about these spiritual things.” The next Sunday that person was in church. Others had been visited by him in the hospital. One family had been helped so much through a personal crisis back then that they arranged to visit with him during this return visit so he could help guide them through a present crisis.

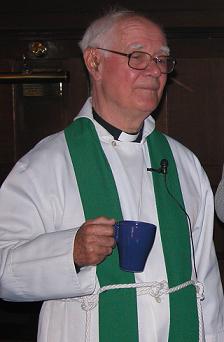

At 9:45 the church bells pealed, announcing to the village that the service was about to start. The procession, from the rear of the church, included Polkinghorne, now in the white and green vestments. When he preached, it was ten minutes on the dot. Polkinghorne told me that a church official heard him preach back in the day and said that the sermon was “Brisk, but a reverent brisk.” Laughing, Polkinghorne said, “I want that on my tombstone.”

At the Eucharist time, row by row, people went to the altar to receive the elements, the wafer dipped in the cup and handed to the worshipers. The use of the common cup had been banned because of swine flu.

At the conclusion, during the coffee time, people swarmed around him. He was a rock star to them. Some had seen him recently when he was on the BBC discussing C.S. Lewis. Others had seen him discussing embryonic stem cell research. Several had attended one of his recent lectures at Oxford. One tried to engage him as to whether the book of Genesis could be literally true.

“I still remember his first sermon,” one parishioner told me. “In telling us why we didn’t need to be afraid of science he used the example of a pot of boiling water on the stove. ” It is one of Polkinghorne’s favorite examples of showing how science and religion don’t have to be hostile to each other. One can inform the other. But fundamentally, they serve different purposes. Science can tell us why the water was boiling – what went into creating the heat that raised the water temperature to the boiling point. But science can’t tell us why the water was put on the stove in the first place. It was put there to prepare a cup of tea – would you care to have one with me, he asks?

At age 79, Polkinghorne is still writing. He just finished his thirtieth book, this one on reading scripture. “The Bible is more of a laboratory notebook than a literal history,” he says.

Back in Cambridge, he celebrates the Eucharist each Wednesday at the local church, and occasionally on Sundays. He says the Daily Office in the morning, and lunches regularly at the Queens’ dining room. Regarding his work on quark theories and his research in general, he is fond of making the following statement. But he could also be talking about himself: “If science teaches us anything, it’s that the world is surprising.”