Every Friday, “Science and the Sacred” features an essay

from a guest voice in the science and religion dialogue. This week’s

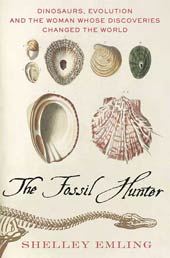

guest entry was written by Shelley Emling. Emling is a freelance writer for the International Herald Tribune and a former foreign correspondent based in London. Her new book The Fossil Hunter

— which goes on sale today — tells the real-life story of Mary Anning, a poor 19th century girl whose fossil discoveries helped change our view of the Earth’s history.

Exiting the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History last weekend, I found myself caught in a science-religion crossfire.

Across Independence Avenue stood a handful of Christians carrying placards encouraging the museum’s visitors to forego the evolutionary leanings of Darwin. On the steps of the museum stood an increasingly vocal crowd chanting Darwin’s name over and over.

For several minutes, the two sides traded insults and it wasn’t long before the hoots and hollers reached a frightening crescendo.

The incident – also witnessed by my 11-year-old son – raised the following question in my mind for the umpteenth time: are Christianity and Darwinism mutually exclusive? Fortunately, as I’ve come to find out, there’s a growing movement between the two fronts that says one can have faith in both religion and science.

I began reading up on the subject after recently writing a nonfiction book titled The Fossil Hunter

on the life of Mary Anning. Anning was a dirt-poor girl who exhumed one never-before-seen prehistoric monster after another from its Jurassic tomb in the cliffs along England’s southern coast in the early 1800s.

Darwin and others pointed to her fossil finds — including many of the world’s first ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and pterosaurs — as proof that new ideas about Earth’s history were inevitable.

According to most accounts, Anning remained a deeply religious woman her entire life, one who could often be found praying or reading the Bible and who almost never missed a Sunday service. Apparently she saw the beauty of God’s handiwork in the coastline she knew so intimately even while others were using her fossils to raise questions about the biblical account of scientific history.

Anning’s close friend, Anna Maria Pinney, wrote of how the two often talked of the idea of creation and other spiritual topics. “To think that life shall never have an end quite fills the mind, but to think of God without a beginning is more than a created being can comprehend,” she wrote.

As Anning aged, and began working alongside Britain’s clique of British male geologists — most of them Anglican clergymen — there were countless attempts to use biblical stories to explain the new knowledge about the natural world that was resulting from Anning’s fossil discoveries.

For example, the fact that fossils sometimes were found at high altitudes was taken as proof that the global flood had been so overwhelming it had reached to the tops of the highest mountains.

No doubt Anning would have been bowled over to learn that – some 200 years later – many are still seeking ways in which to reconcile religion with science.

But Simon Conway-Morris, the renowned paleontologist at Cambridge University, is just one scientist who argues that religion and science are completely compatible.

The British professor believes evolution isn’t as accidental or random as one might suspect. In his opinion, if evolution began all over again, human intelligence would develop pretty much in the same way as it has. Conway-Morris emphasizes that developments happen as a result of pre-existing conditions, such as the need for blood cells to have hemoglobin in order to transport oxygen. Evolution, therefore, works only because it plays out within a certain set of rules.

Evolution “is after all only a mechanism, but if evolution is predictive, indeed possesses a logic, then evidently it is being governed by deeper principles,” he recently wrote. “Come to think about it so are all sciences; why should Darwinism be any exception?”

Peter Hess, the Faith Project director at the National Center for Science Education in Oakland, Calif., also believes that scientific inquiry and religious belief are not mutually exclusive.

“Because the evidence for evolution is so overwhelming, we must consider it to be a truth about the natural world — the world which we as people of faith believe was created by God, and the world made understandable by the reason and natural senses given to us by God,” he recently wrote. “Denying science is a profoundly unsound theological position. Science and faith are but two ways of searching for the same truths.”

Most telling is that the proportion of Christians among the science faculty in certain departments at Oxford and Cambridge universities — such as the Earth Sciences Department in Cambridge or the Physics Department in Oxford — appears higher than the national average, says Denis Alexander, director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, an academic research enterprise based at Cambridge.

“There are generally more Christians in the sciences than in the humanities,” he said.

And what about the clergy? Michael Zimmerman, a biology professor at Butler University in Indianapolis, said his work with the Clergy Letter Project has led him to believe that a vast number of religious leaders of all denominations are fully comfortable with science. He argues that religious fundamentalists are the exception, and that they tend to assert themselves “more aggressively” to maintain their waning influence.

Yet the public remains sharply divided.

A Gallup poll released this year found that 39 percent of Americans “believe in the theory of evolution,” while a quarter said they do not believe in the theory, and another 36 percent said they don’t have an opinion either way.

Even in Anning’s native and more secular Britain, less than half — or 48 percent — of citizens said in a 2006 survey that they adhere to the theory of evolution. And about three-fourths of British respondents to a recent survey said that science is unable to explain everything.

Today many people would love to believe that science has all the answers. But people say there are plenty of mysteries that have yet to be explained.

Despite centuries of astronomical observations and decades of space exploration, it is thought that more than 90 percent of the mass in the universe still hasn’t been detected.

Scientists can’t explain a human being’s free will, which may or may not be just an illusion, and there’s still no rock-solid scientific reason as to why everyone must die.

In the end, as in Anning’s time, there are still many who have absolute faith in the fact that species never evolve or become extinct.

Many others believe that neither evolution nor extinction denies the hand of God.

Still others don’t believe in God at all.

So, in this year of Darwin anniversaries, can science and religion ever be fully reconciled? For the first time in a long time, I am hopeful. As more scientists come out in favor of faith, and more clergy accept the teachings of science, perhaps reconciliation is inevitable.