“…were all the sorrows of the world to be crowded into my heart they would, I feel, all vanish, when in the presence of Bahá’u’lláh. It is as if I had entered Paradise.” – Prince Zaynu’l-‘Abidín Khan

The calmness and serenity of the infant was such as to amaze the mother. Khadijih Khanum could not recall if he ever cried or waxed restless. Bahá’u’lláh, born Husayn ‘Alí on 12 November 1817, was a child of kind demeanour. But his keen intellect caught his father’s attention. “He is a little short”, the mother once remarked to her husband Mírzá Buzurg while watching the child walk. “But do you not know how intelligent he is and what a wonderful mind he has!” the father exclaimed with pride.

Bahá’u’lláh was the scion of one of the great aristocratic families of Persia. The family traced its ancestry to the last Sassanian King, Yazdegerd III, who reigned before the Muslim conquest of Persia. Opulence and privilege were his lot, respect and adoration his birth-right. His summer months were usually spent in the countryside outside the capital Tehran in the district of Núr. He had a great love for nature and spent much of his time outdoors roaming in the meadows and woodlands that belonged to his father. Sometimes he ventured out on foot, other times on horseback. The indoors were no less princely. Mírzá Buzurg, a vizier at the Sháh’s court, had built a stately mansion in Takúr. The mansion was erected in the best traditions of Persian masonry and carpentry. The palatial halls would merit only the most valuable carpets and the high walls showcased the vizier’s own masterful calligraphy. “Buzurg”, or “great”, was the title given by the Sháh to Mírzá Abbás-i-Núrí in recognition of his skill as a calligrapher. The scent of rose water filled the rooms and the warble of nightingales entered the halls through oriental windows and arched doorways. Silver samovars lovingly supplied exquisite porcelain teacups with afternoon tea and fresh mint leaves added to the aroma. The tea leaves came directly from the nearby estates. A dedicated staff of servants did all the work, including the preparation of saffron rice with tender lamb garnished with local herbs. Fruits of the season, rock melons, grapes, pomegranates and cherries, were ever-ready for a royal bite in the embrace of hand-crafted bowls representing the finest Persian pottery. Master-gardeners tended to the vizier’s rose gardens with motherly care and attention. Mírzá Buzurg was still a rich man and his properties included a number of country estates as well as a complex of houses in Tehran. In addition to his ministerial duties in Tehran, Mírzá Buzurg was the appointed governor of Burujird and Lorestan provinces.

The boons of wealth and power however held little sway over Husayn-‘Alí. Precociously insightful, he was early to see beyond their seeming luster. Once he was taken to see a puppet show in Tehran. The play was called Sháh Sultán Salím. Princes, dignitaries and notables from the capital attended the occasion, as much for entertainment as for making an appearance. Bahá’u’lláh was sitting in one of the upper rooms of the building, observing the scene. A tent was pitched in the courtyard and soon small puppet-like figures appeared. One of them, a town crier, raised the call: “His Majesty is coming! Arrange the seats at once!” The play was a ridiculous imperial fanfare, a delightful feast to the senses. The puppets vividly portrayed a menagerie of characters — proud princes with hats and sashes, footmen wielding battle axes, executioners carrying bastinadoes and a haughty king marching along with great pomp and circumstance. The show began with a scene of a royal entourage appearing at a venue of execution. Thieves were decapitated with blood-like liquid pouring out, trumpets were sounded, and shortly wars were waged and a pall of smoke enveloped the whole tent. An evil rebellion was quelled and cannons boomed at the final battle, establishing the heroic king triumphant over his nefarious enemies.

The vizier’s son watched the play with great amazement. When the play had ended and the curtain was lifted, the lone puppeteer emerged from behind the tent carrying a box under his arm. Young Bahá’u’lláh asked the man about the contents of the box. The puppeteer described to the child how the impressive and lavish display he saw is now contained within the little box under his arm. The sight of that box made a piercing impression on young Bahá’u’lláh. All the trappings of this world suddenly seemed to him like that same spectacle. “Erelong these outward trappings, these visible treasures, these earthly vanities, these arrayed armies, these adorned vestures, these proud and overweening souls, all shall pass into the confines of the grave, as though into that box”, he recalled the puppet show some half a century later as he lay in exile in far-off Adrianople (Edirne).

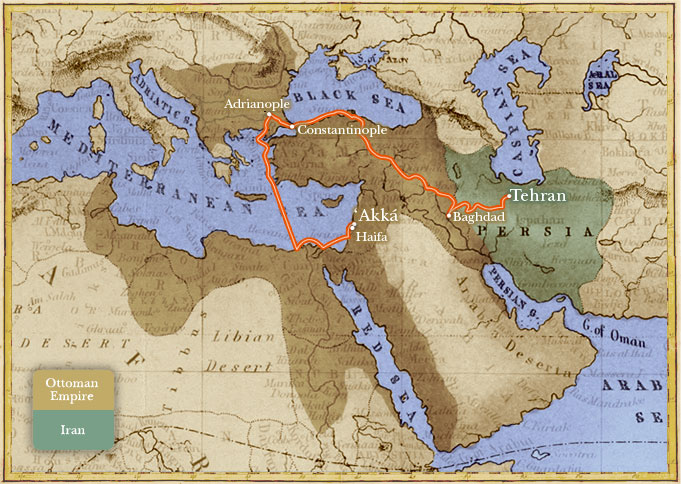

His pampered and privileged youth was now but a distant whiff from the past. He had been brought to Rumelia from the Ottoman Capital in a carriage used for baggage, and housed, with his family, in the dead of winter in a summer house unfit for residency. Neither he nor his wife and children had the necessary raiments to protect themselves from the freezing cold. After accepting the Báb as a Messenger of God, and publically proclaiming his cause at the age of twenty-seven, his inherited properties were confiscated, his possessions looted and his body thrown into the infamous Black Pit. But his fate in exile and imprisonment was sealed after thousands of Bábis and other Persians began flocking to him and to seek his wisdom as “Him Whom God Shall Make Manifest” prophesied by the Báb. He had announced his own Messengership humbly. First to his family and thereafter to his immediate companions at the time when he was held in house arrest in Baghdad. But the news of his knowledge and his radiant presence, coupled with his inspiring revelations that were being disseminated in Writing, began to spread from mouth to mouth, and to attract curiosity and animosity in equal measure. Now in Adrianople, at fifty-one, he had already endured 16 years of banishment and incarceration in various parts of the Ottoman Empire. Yet even as he lay robbed, ridiculed and rejected, his mind remembered the triviality that is earthly glory, and his heart rejoiced in the eventual end of all earthly sorrow.

“In the eyes of those possessed of insight all this conflict, contention and vainglory hath ever been, and will ever be, like unto the play and pastimes of children.”

“Should prosperity befall thee, rejoice not, and should abasement come upon thee, grieve not, for both shall pass away and be no more.”

– Bahá’u’lláh

November the 12th, 2012, marked the 195th anniversary of the birth of Bahá’u’lláh