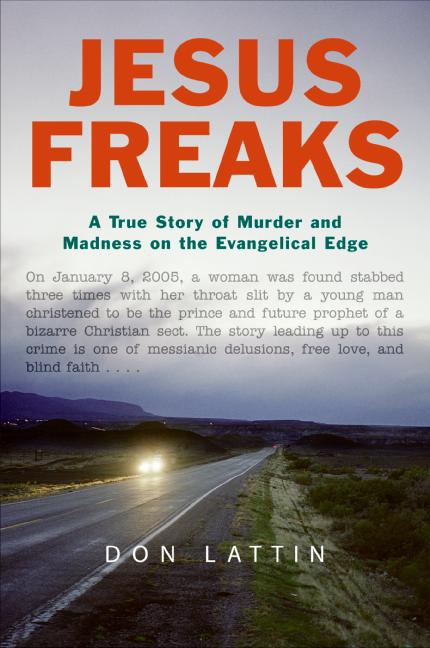

One of the most unshakeable reading experiences I’ve had in the last year is Don Lattin’s Jesus Freak: A True Story of Murder and Madness on the Evangelical Edge. Taking a cue from Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, Lattin uses the story of a freakish murder-suicide as the occasion to research the nature of cultish religious belief. Lattin’s sect is a little less known than Krakauer’ fundamentalist Mormons–in Jesus Freaks we follow the founding and flourishing of the Children of God/Family International. The group was initially an offshoot of sorts from the Jesus Movement, the evangelical hippie revival of the 1970s. But under the apocalyptic teaching of a self-described messiah and “End-Time Prophet” named David Berg, the Children of God became a corrupted, sexualized regime that drove its decedents to murderous acts.

One of the most unshakeable reading experiences I’ve had in the last year is Don Lattin’s Jesus Freak: A True Story of Murder and Madness on the Evangelical Edge. Taking a cue from Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, Lattin uses the story of a freakish murder-suicide as the occasion to research the nature of cultish religious belief. Lattin’s sect is a little less known than Krakauer’ fundamentalist Mormons–in Jesus Freaks we follow the founding and flourishing of the Children of God/Family International. The group was initially an offshoot of sorts from the Jesus Movement, the evangelical hippie revival of the 1970s. But under the apocalyptic teaching of a self-described messiah and “End-Time Prophet” named David Berg, the Children of God became a corrupted, sexualized regime that drove its decedents to murderous acts.

You anticipate in

your introduction that a lot of evangelical Christians will have a problem with

the title “Jesus Freaks.” You’ve got that right–this is a book about

cultists, and it sounds like you are conflating them with other Jesus

followers. Why did you choose this title?

When I did the

historical research on Berg’s beginnings, two things were clear. One, that he

definitely came out of the evangelical movement. He was in ministry with his

mother and with his children and ordained with the Christian Missionary

Alliance. And when the Children of God started, they were originally called

Teens for Christ. He initially had support within the evangelical movement

until some people started hearing what was really going on underneath.

What were

Bergen’s evangelical roots?

He started out kind

of Holiness Pentecostal. His mother was a pretty well known evangelist in the

1920s in the mode of Aimee Semple McPherson. That’s where he really learned the

tricks of the evangelical trade.

How does someone

transition from garden variety evangelical preacher to “The End-Time

Prophet”?

This was a guy who

was a miserable failure as a preacher and evangelist. He was 50 years old when

he started this thing, and he had been in his mother’s shadow for so long. I

think a lot of it was he was just mad at the world because of the failures that

he had in his own ministry. Then, when he got this following, I think it

convinced him more and more that he was a prophet. His time had finally

come–you know, the whole Messianic complex.

Berg is often in the background in this book, which

I think is probably how he existed for his followers, too.

That’s the thing.

How can someone have this much power over people that had never even see him?

They didn’t even know what he looked like. They weren’t allowed to see pictures

of him. He was a drawing of a lion–a friendly lion–on all the literature, his

photograph with a drawing of a lion for the head.

Was Berg central

in the minds of the community as the leader of this movement?

No doubt about it.

He wrote thousands of missives. I talked to people who were in his inner

circle, one that was anonymous in the book. He said that [Berg] never went

anywhere without someone carrying a tape recorder. A lot of his writings were

just his rantings. He was basically a religious drunk. He would get drunk

around the dinner table and start talking, and that’s kind of why he said such

outrageous things. But it was later edited and checked, and they still sent it

out.

You write that

cults show us how religions are born, and you draw a connection between David Berg

and Catholic pedophilia and Muslim terrorists. What

connects those three different groups?

In a way you could

say that all religions start as cults, or sects. Christianity started as a

Jewish sect, right? And take the Mormon church–a lot of people still think

that Mormonism is a cult. People are so interested in studying the development

of Mormonism because there’s a written record. Most religions are from

antiquity, and it’s really hard to see what was going on. With Berg–he wrote

down everything. So you can see how the theology develops.

Do you see Ricky

as kind of a symbol for products of religious upbringings?

As a religion writer

over the years, I have come across a lot of people who were raised in strict,

conservative evangelical–some would say fundamentalist–churches that feel like

it was abusive, that they’re survivors of Christianity.

[David Hoyt] said,

“The lesson for me is to be very, very careful not to give your loyalty to any

new teaching, new prophet, special revelation. My loyalty is to God and Jesus

Christ and the Holy Spirit, and to no pastor, teacher or evangelist. I don’t care how big

a following they have. No pastor or leader or man is infallible. I’ve got that warning burned on my soul.”

That’s why I think this a book that Evangelicals should read.