I was introduced to Philip Jenkins‘ work several years ago through his Atlantic cover story, “The Next Christianity.” There, Jenkins explained that the center of global Christianity was shifting to the southern hemisphere. In The Next Christendom and the two related titles that followed, Jenkins argued that Christianity today is not as Western as we believe it to be–and it’s becoming less so all the time.

I was introduced to Philip Jenkins‘ work several years ago through his Atlantic cover story, “The Next Christianity.” There, Jenkins explained that the center of global Christianity was shifting to the southern hemisphere. In The Next Christendom and the two related titles that followed, Jenkins argued that Christianity today is not as Western as we believe it to be–and it’s becoming less so all the time.

Your book’s first sentence is “Religions die,” which is rather shocking to the way we see religions existing today: I think we expect cults to fade away, but not established religions. Why are you concerned, at this moment, to write about the vanishing of faith traditions?

Religions really do die. We think of ancient religions like those of the Aztecs or Mayas, which had millions of followers, not to mention copious scriptures. Also, something like the Manichaean faith once stretched from France to China, but that is now extinct. The Zoroastrian religion is not exactly extinct, but it has gone from being a vast world religion to the creed of a few hundred thousand believers.

But also, religions die in particular times and places, in the sense that they once dominated whole countries, but then cease to exist there. The religion is not dead in the sense that it still continues somewhere else, but that is a local kind of death. My book is mainly about Christianity in the Middle East, but I might also look at Islam in Spain, or Buddhism in most of India. Just within our lifetimes, we probably will see the extinction of Christianity in Iraq and probably Palestine.

What interests me about the topic is that so little has ever been done on it. We really don’t know why religions die, and if they do, in what sense they might leave ghosts. One thing that strikes me is how much a dead religion influences its successor – how for instance the old Christianity left its mark on the successor faith of Islam.

Finally, there is a major theological issue that nobody addresses, the theology of extinction. How do Christians explain the death of their religion in a particular time and place? Is that really part of God’s plan? Or maybe our time scale is just too short, and one day we will realize why this had to happen. But as I say, nobody is really discussing these questions.

The fact you find the remark “religions die” so shocking proves that I am right to be exploring it!

Give us a sense of the scope of the Eastern Christianity that, as you explain, dominated the first half of Christian history.

Its sheer scale is astonishing. Already by the seventh century, the Church of the East – the Nestorian church – is pushing deep into Central Asia. Nestorian monks were operating in China before 550, and nobody knows when the first Christian actually saw the Pacific – that would be a great historical novel for someone to write!

As I write in the book, “Before Saint Benedict formed his first monastery, before the probable date of the British King Arthur, Nestorian bishops functioned at Nishapur and Tus in north-eastern Persia. Before England had its first Archbishop of Canterbury, the Nestorian church already had metropolitans at Merv in Turkmenistan and Herat in Afghanistan, and churches were operating in Sri Lanka and Malabar. Before Good King Wenceslas ruled a Christian Bohemia, before Poland was Catholic, the Nestorian sees of Bukhara and Samarkand achieved metropolitan status. So did Patna on the Ganges, in India.” What I find fascinating about that is how that history violates our usual assumptions about what Christianity looked like in the so-called Dark Ages – about what it was, and where it happened.

Also, this Eastern world has a solid claim to be the direct lineal heir of the earliest New Testament Christianity. Throughout their history, the Eastern churches used Syriac, which is close to Jesus’s own language of Aramaic, and they followed Yeshua, not Jesus. Everything about these churches runs so contrary to what we think we know. They are too ancient, in the sense of looking like the original Jerusalem church; and they are too modern, in being so globalized and multi-cultural.

Just a suggestion. Perhaps we should think of these eastern communities – the Nestorians and Jacobites – as the real survivors of ancient Christianity. In that case, the great Western churches we know, the Catholic and Orthodox, are the “alternative Christianities.”

What aspects of Eastern Christianity would you most like to recover?

Undoubtedly, its ability to relate to other cultures and religions in a way that does not necessarily mean conceding any fundamental claims on either side. These Christians interact freely with Buddhists and exchange ideas to the point that some use a lotus-cross symbol. At the same time, this is an authentic version of ancient Christianity – liturgical, monastic and mystical.

From its earliest ages, Christianity has always been a vastly wider, more diverse and more global faith than we ever give it credit for.

Your book is concerned with the conflict between Islam and Christianity. Is there any sense in which the story of those two faiths is more than just a history of conflict?

Absolutely. Christians survive perfectly well for centuries under Muslim regimes, and the relations between the two are often excellent. In fact, Islam borrows massively from those ancient Christian churches. They borrow a lot of the architectural styles of mosques, the worship practices, and customs like Lent, which becomes the Muslim Ramadan. In fact, if a sixth or seventh century Eastern Christian came back today, that person would probably feel more at home in a mosque than a typical Western church service. That comfort level might change once they explored the doctrines being taught, but the general atmosphere would be very similar. The more you look at these Eastern Christianities, the easier it is to understand that Islam and Christianity emerged as sister faiths.

If those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it, what lessons does The Lost History of Christianity have for us today?

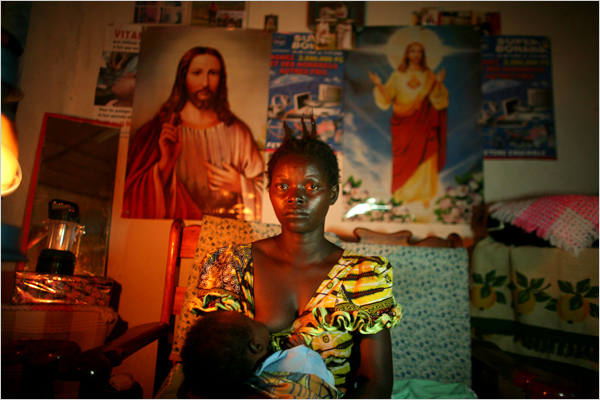

By far the biggest lesson for me is not so much how some churches die, but how others survive. We should look at communities like the Copts in Egypt, who have survived under Muslim rule for almost 1400 years. We have much to learn about their adaptability in the face of dominant languages and cultures, their ability to learn the new languages of power, without abandoning their core beliefs. Christians around the world have vast accumulated experience about dealing with minority status, and with exclusion from power and influence on a scale vastly greater than that faced by any modern church in the West. How have they done it?

What kinds of Christian decline have happened more recently? What do you see happening now?

By far the largest change is in the Middle East, the region between Persia and Egypt. As recently as 1900, the Christian population of that whole region was almost ten percent, but today it is just a couple of percent, and falling fast. Particularly if climate change moves as rapidly as it some believe, the resulting tensions could reduce Christian numbers much further. Egypt would be the most worrying example here. Might that 1,400 year story come to an end in our lifetimes?

Europe is nothing like as serious an issue. The number of active or committed Christians certainly is declining, but the churches don’t face anything like what is happening in the Middle east. There is no plausible prospect of a Muslim regime anywhere in Western Europe, or of the recreation of the social order on the lines of Muslim law. Realistically, people of Muslim background will constitute a substantial minority of the European population, rather than a majority, and it is far from clear that most will define themselves primarily according to strict religious loyalties. European Christianity may be in anything but a healthy state, but Islam need not be its greatest cause for concern.

Matters are very different in other countries of Africa and Asia, where Muslims and Christians are in deep competition. We could imagine wars and persecutions that could uproot whole societies.