A few

years ago, a Jewish student in the boarding school where we lived came to my

apartment in tears. Her dormitory was filled, top to bottom, with Christmas.

Wreaths. Lights. Bows. Secret Santas. She just didn’t want to feel so

different, so excluded, so… Jewish.

She came

to my apartment with a friend, a Christian. And as we started to talk the

Christian student shared some of the same thoughts. Bows and wreaths and Secret

Santas weren’t really connected to Christmas for her as a Christian. In fact,

they were distractions. Fun, maybe. But they seemed like ways to avoid the

dramatic idea of God coming into the world in the form of a baby. In the

context of holiday decorations and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, this

Christian student felt so different, so excluded, so… Christian.

The

Christian student demonstrated compassion for her Jewish friend, and she wasn’t

trying to say that their experience was the same. And yet there were points in

common. I talked to both of them about the privilege it can be to know yourself

as set apart. Their religious identities differentiated them from their

holiday-loving peers. Living in their dorm in December felt awkward,

alienating, upsetting, and yet I urged them to consider how it also helped them

to define themselves in terms of their own core values, family traditions, and

religious beliefs.

Two recent articles reminded me of those conversations. First, there’s Ross Douthat’s column in the New York Times, “A Tough Season for Believers.” Douthat shares the view of the Christian student mentioned above–all this tinsel and mistletoe is not at all what I believe in, so how should I respond? He calls for engagement with the culture around us, a response based upon the Word made flesh, full of grace and truth. Douthat’s article is worth reading on the whole, but I particularly appreciated his concluding line:

Christians need to find a way to thrive in a society that looks less and less like any sort of Christendom — and more and more like the diverse and complicated Roman Empire where their religion had its beginning, 2,000 years ago this week.

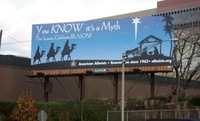

I’ve also come across a few articles related to an advertising campaign by various atheist groups who want to debunk the myth of Christmas. In case you can’t read the print on the photo, this one reads: “You KNOW it’s a Myth. This Season, Celebrate REASON.” As James McKinley reports for the New York Times, similar ads have shown up on the sides of busses, with taglines such as “Millions of people are good without God.” One atheist in support of the ads said, “”It can be pretty lonely for a nonbeliever at Christmastime around here. There is so much religion,” Mr. McDonald said. “We thought, ‘What the heck? Nobody owns December.’ “

I’ve also come across a few articles related to an advertising campaign by various atheist groups who want to debunk the myth of Christmas. In case you can’t read the print on the photo, this one reads: “You KNOW it’s a Myth. This Season, Celebrate REASON.” As James McKinley reports for the New York Times, similar ads have shown up on the sides of busses, with taglines such as “Millions of people are good without God.” One atheist in support of the ads said, “”It can be pretty lonely for a nonbeliever at Christmastime around here. There is so much religion,” Mr. McDonald said. “We thought, ‘What the heck? Nobody owns December.’ “

Christians think it’s hard at Christmastime. Jews think it’s hard too. Atheists are lonely. I can only imagine that the remainder of the religious spectrum shares a similar response to the hubbub of December. Funny. Might Christmas be a season that opens up dialogue among religious groups–Christians included–who feel alienated by American culture? Perhaps the fact that many Americans have lost sight of the “reason for the season” will actually inspire conversation and connection. Perhaps our response to Christmas will bring together a surprisingly diverse range of people. Perhaps it will remind us of a baby born in a manger, welcomed by both the shepherds and the kings.