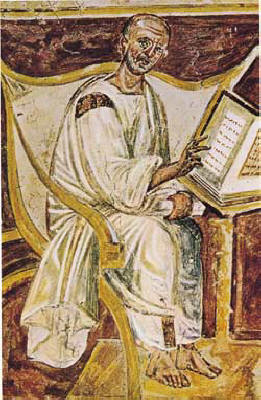

The shadow of Augustine of Hippo looms large over the entire subsequent development of the doctrine of Original Sin. We’ll get into his authorship of the doctrine qua doctrine in a minute, but first let’s remember the importance of his biography. If Paul was a Jew’s Jew, Augustine was a  Neoplatonist’s Neoplatonist. Schooled in the philosophy of Plotinus, Augustine even converted to a Neoplatonic religion, Manicheaism, in his 20s.

Neoplatonist’s Neoplatonist. Schooled in the philosophy of Plotinus, Augustine even converted to a Neoplatonic religion, Manicheaism, in his 20s.

As you might guess, Neoplatonism took strands of Platonism and magnified them, most significantly, dualism. Prior to his conversion to Christianity, Augustine’s philosophy and religion both held to a strict separation between God and humanity, good and evil, spiritual and material. (Both Doug and I have written about how Augustine’s version of the world didn’t necessarily jibe with the Hebrew worldview of Jesus and the Apostles.) Augustine’s dramatic conversion to a religion in which God (good) took on human flesh (evil) was a tough one for him to swallow and, from one angle, much if his writing was an attempt to mesh platonic ideas with the biblical narrative.

In the comment sections of previous posts in this series, some have quoted the Catholic Encyclopedia to note that Augustine was not the author of the doctrine of Original Sin. But it’s similar to the doctrine of the Trinity — others (e.g., Tertullian) may have written about it in primitive ways, but it was Augustine who matured the doctrine.

Likewise with Original Sin. Augustine’s opponent on this issue was Pelagius, an English monk, whose name is now spat at me and others who question Augustine’s version of the doctrine. It’s impossible to know what Pelagius really thought and wrote, since we know him primarily through Augustine’s refutations, so it’s better to think of Pelagius as a foil for Augustine’s doctrine than anything else. This is not to say that he wasn’t a church leader with a massive following in his day — he was. In fact, there’s a novel to be written by someone about what would have happened had Pelagius won the day theologically instead of Augustine.

Supposedly, Pelagius blamed the moral laxity that he saw around Rome on Augustine’s doctrine of Original Sin. According to Augustine, human beings have all inherited guilt from Adam and Eve and are completely reliant upon God’s grace for any good work. Pelagius thought that this contradicted the biblical narrative, in which human beings are again and again told to behave in ways that accord with God’s ways and are subsequently rewarded or punished based on their behavior.

Augustine, on the other hand, argued that human beings are incapable of the very good works that the Bible commands. It’s only by God’s grace, held in absolute sovereignty, that human beings are saved or capable of any good works. Augustine does not deny free will, per se (that comes later), but he does believe that human beings lost their moral free will in Adam’s sin. Neither, it should be noted, do Pelagius’ followers, the “Semi-Pelagians,” deny the reality of sin.

that the Bible commands. It’s only by God’s grace, held in absolute sovereignty, that human beings are saved or capable of any good works. Augustine does not deny free will, per se (that comes later), but he does believe that human beings lost their moral free will in Adam’s sin. Neither, it should be noted, do Pelagius’ followers, the “Semi-Pelagians,” deny the reality of sin.

So, no surprise, it turns out that we’re dealing with two nuanced positions that reallty are not as far apart as some would make them out to be.

What we should note, however, is how Augustine took the notion of inherited sin further than Paul had in Romans 5. Here’s the bottom line:

- Eastern (Orthodox, Coptic, and Byzantine Rite Catholic) Christians take Paul to mean that our inheritance from Adam is death.

- Western (Augustinian) Christians take Paul to mean that our inheritance is death and guilt.

In other words, we don’t only lose our immortality because of Adam’s sin, but each of us stands guilty before God because of his sin.

Thus, you can see how, once again, our understanding of this and our possible agreement or disagreement with Augustine hinges on our reading of Genesis 2-3. But is also hinges on whether you believe that God would punish you for the sin of another. Augustine’s answer to this this question is Yes, for he said that unbaptized infants, bearing Adam’s guilt, were consigned by God to hell.