When we last heard from our intrepid doctrine, Augustine had taken Paul’s interpretation of Genesis 2-3 in Romans 5 and taken that to mean that Adam’s sin conferred not only death on the entire human race, but also guilt. This was a big step, to be sure, and, as I’ve written, it hinges on a particular reading of the second creation narrative in Genesis and on a particular biology of the transmission of moral standing via semen. Some of my readers find both of these fairly dubious.

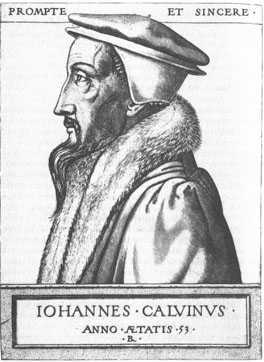

A thousand years after Augustine, John Calvin came along and ginned up the Reformation that Martin Luther had begun just a few years earlier. Calvin in his monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion, Calvin took the doctrine of Original Sin one step further than Augustine, arguing that our inherited sinfulness has erased virtually all remnant of the imago dei in us — God might have said, “Let us make man in our image,” but the subsequent sin of Adam expunged that image:

A thousand years after Augustine, John Calvin came along and ginned up the Reformation that Martin Luther had begun just a few years earlier. Calvin in his monumental Institutes of the Christian Religion, Calvin took the doctrine of Original Sin one step further than Augustine, arguing that our inherited sinfulness has erased virtually all remnant of the imago dei in us — God might have said, “Let us make man in our image,” but the subsequent sin of Adam expunged that image:

“Therefore original sin is seen to be an

hereditary depravity and corruption of our nature diffused into all parts

of the soul . . . wherefore those who have defined original sin as the

lack of the original righteousness with which we should have been endowed,

no doubt include, by implication, the whole fact of the matter, but they

have not fully expressed the positive energy of this sin. For our nature

is not merely bereft of good, but is so productive of every kind of evil

that it cannot be inactive. Those who have called it concupiscence

[a strong, especially sexual desire, lust] have

used a word by no means wide of the mark, if it were added (and this is

what many do not concede) that whatever is in man from intellect to will,

from the soul to the flesh, is all defiled and crammed with concupiscence;

or, to sum it up briefly, that the whole man is in himself nothing but

concupiscence.“

Calvin’s acolytes seized upon the idea of “hereditary depravity” and made it the opening salvo of the TULIP doctrine:

Total Depravity

Unconditional Election

Limited Atonement

Irresistable Grace

Perseverance of the Saints

The first question I always ask 5-point Calvinists is this: If you

believe in total depravity of the human intellect, how can you be so

damn certain that you’re right about total depravity? The answer

usually seems to be something about the “plain meaning of scripture.”

That quibble aside, Calvinists make clear that total depravity is not the same as absolute depravity. While the latter allows for no good in humans, the former merely means that every aspect of the human being is besmirched, but that good is still possible within a human. (No, I don’t quite see the difference either.)

But total depravity does mean that the human being is not capable of producing anything good, not capable of doing anything that is pleasing to God.

What this promotes is the sovereignty of God, a doctrine which, it must be noted, Calvinists value more highly than any other. Acknowledging the sovereignty of God, they argue, necessitates the doctrine of human depravity because if God is totally sovereign, then we are totally lacking in sovereignty.

As I have found with the doctrine of Original Sin in general, it seems to me a solution (God’s sovereignty) in search of a problem (total depravity). It also seems to me that I can affirm God’s sovereignty without accepting total depravity.

So, what say you? Are any of you willing to come to the defense of Calvin’s theological foe, Arminius, as some of you were for Pelagius?

(BTW, I officially ban comments to the effect of “Need proof of depravity? Look around!” and “GK Chesterton said that Original Sin is the one doctrine that is empirically provable. Puh-leeze.)