Depending on what version of the Bible you use, the word meditate appears about fifteen times in the Old Testament. (It’s not used at all in the New Testament.) Fourteen of the Old Testament uses are in the Psalms, six in Psalm 119.

The one reference to meditate not in a psalm is a famous line from the opening of the book of Joshua. Moses has just died, and God speaks to Joshua, who will be leading the people of Israel into their Promised Land:

“Moses my servant is dead. Get going. Cross this Jordan River, you and all the people. Cross to the country I’m giving to the People of Israel. . . . I’ll be with you. I won’t give up on you; I won’t leave you. Strength! Courage! . . . Make sure you carry out The Revelation that Moses commanded you, every bit of it. Don’t get off track, either left or right, so as to make sure you get to where you’re going. And don’t for a minute let this Book of The Revelation be out of mind. Ponder and meditate on it day and night, making sure you practice everything written in it. Then you’ll get where you’re going; then you’ll succeed.” (Joshua 1:2-8)

We can learn some things about the concept of meditation from this passage. To meditate means to keep something in mind–in fact, to keep it in the front of your mind. God tells Joshua that his success at leading the people into Canaan is tied to his meditation on the books of Moses (commonly understood to be Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy).

Meditation and practice are linked. “Ponder and meditate on it day and night, making sure you practice everything written in it.” God doesn’t want Joshua to merely think about his Word. He also wants Joshua to put it into practice. Meditating on God’s Word and living God’s Word are, God says to Joshua, inextricably tied together.

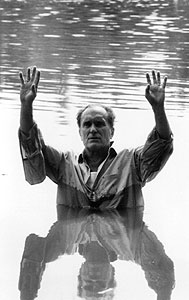

Pastor and theologian Eugene Peterson translated The Message, and he writes that the Hebrew word for meditate is hagah, which can also be translated “growl” or “chew.” For instance, that’s the word used in Isaiah’s prophecy: “Like a lion, king of the beasts, that gnaws and chews and worries its prey” (Isaiah 31:4). The kind of meditation to which God calls Joshua, and the kind of meditation to which the psalmist calls all of us, is more like a dog chewing a bone, or a lion working over a carcass, than what we usually think of as meditation.

Pastor and theologian Eugene Peterson translated The Message, and he writes that the Hebrew word for meditate is hagah, which can also be translated “growl” or “chew.” For instance, that’s the word used in Isaiah’s prophecy: “Like a lion, king of the beasts, that gnaws and chews and worries its prey” (Isaiah 31:4). The kind of meditation to which God calls Joshua, and the kind of meditation to which the psalmist calls all of us, is more like a dog chewing a bone, or a lion working over a carcass, than what we usually think of as meditation.

Peterson writes,

“Meditate” is far too tame a word for what is being signified. “Meditate” seems more suited to what I do in a chapel on my knees with a candle burning on the altar. Or my wife sitting in a rose garden with the Bible open in her lap. But when Isaiah’s lion and my dog meditated, they chewed and swallowed, using teeth and tongue, stomach and intestines.

The opening of the first psalm is usually translated,

Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked,

or take the path that sinners tread,

or sit in the seat of scoffers;

but their delight is in the law of the LORD,

and on his law they meditate day and night. (Psalm1:1-2, NRSV, emphasis added)

In The Message, Peterson translates it as,

How well God must like you–

you don’t hang out at Sin Saloon,

you don’t slink along Dead-End Road,

you don’t go to Smart-Mouth College.

Instead you thrill to GOD’s Word,

you chew on Scripture day and night. (Psalm 1:1-2, emphasis added)

If you want to read more, I invite you to check out Divine Intervention: Encountering God through the Ancient Practice of Lectio Divina.

Image from Wikipedia Commons.