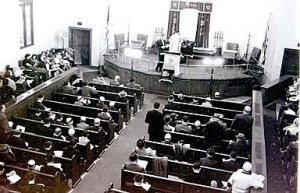

Friends, I delivered the following sermon at a community interfaith Thanksgiving service. Wishing each of you a wonderful holiday, Rabbi Evan

The greatest Rabbi of Jewish history was named Moses Maimonides. Maimonides wrote a classic work of Jewish philosophy known as the Guide to the Perplexed, as well as a book of Jewish law known as the Mishneh Torah, the Second Torah. In addition to his rabbinical duties, Maimonides was a renowned physician, caring for the Sultan Egypt.

As a doctor and rabbi, Maimonides saw the Bible through a scientific rational framework. He struggled to make sense of instances—like the parting of the Red Sea in the Book of Exodus, or the Talking Donkey in the Book of Numbers—that violated the laws of nature. His answer was that some of these supernatural events were built in—preprogrammed to use a computer term—into the world. God wrote them in the computer code of creation.

I Believe in Miracles

Yet, Maimonides did not give up on the idea of miracles. A miracle for Maimonides did not have to be supernatural. Miracles can be a part of everyday life. Miracles depend on perspective. He had early insight into an idea Albert Einstein later expressed: “There are only two ways to look at the world. One is as though nothing is a miracle. The other is as though everything is a miracle.”

I would add: greater happiness and satisfaction come from the latter. How do we cultivate that perspective? How do we live so that we might proclaim, as did Rabbi Sobel in the text from psalms, “This is the Day God has chosen; let us rejoice and be glad in it?”

Giving Thanks

First, by practicing acknowledgement. In Hebrew, the word for thanksgiving–Hoda’ah–also means acknowledgment. And when we say prayers of thanksgiving, as we did this evening, we are also saying, “I acknowledge this moment, I am aware of this encounter.” Saying prayers of thanksgiving is not just expressing gratitude. It is acknowledging an encounter, an experience, a paying attention to the moment.

My friend Rabbi Rami Shapiro expressed this idea in a wonderful text—I hesitate to call it a poem or a prayer or a teaching. It is all of the above:

Spirituality is living with attention.

Living with attention leads me to thanksgiving

Thanksgiving is the response I have

to the great debt I accrue with each breath I take.

Attending to the everyday miracles of ordinary living

I am aware of the interconnectedness of all things.

I cannot be without you.

This cannot be without that.

All cannot be without each.

And each cannot be without every.

Thanksgiving is not for anything.

It is from everything.

May I cultivate the attention

to allow the thanks that is life

To inform the dance that is living.

To practice acknowledgement is to live with attention. In other words, when we teach our kids to thank you and please, we are not just teaching manners. We are cultivating spirituality. We are teaching a worldview. Sometimes we need a reminder of those same lessons.

How Limits Expand Us

The second way to cultivate a perspective of joy is to embrace limits. This idea may seem counter-intuitive. Limits are constraints. They prevent us from doing certain things or saying certain words. Don’t limits inhabit our pursuit of happiness? Don’t they prevent us from reaching our potential?

The level of malaise and dissatisfaction in our culture prove otherwise. The more unlimited our desires, the more dissatisfied we become. We continually want more. Social critic Gregg Easterbrook calls it the progress paradox: When life gets better, people often feel worse. He asks, “Why do capitalism and liberal democracy, both of which justify themselves on the grounds that they produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number, leave so much dissatisfaction in their wake?”

Jewish wisdom understood this paradox long ago. There is a midrash, an interpretive story, about Adam, the first human being. According to this midrash, Adam was taller than the clouds. The width of his arms encircled the world. Yet, he could exist like that only in the Garden of Eden. In the real world, the world we inhabit, we live with limits. The mystical sages of Jewish tradition go even further. In order for the world to exist, the infinite Adam, the Adam whose head reached over the clouds, cannot exist.

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

In other words, we cannot live without limits. When we embrace them, however, we find meaning in them. Think of marriage: getting married imposes limits on individual behavior. Yet, the relationship thereby created is among the most meaningful and powerful. Neighbors can co-exist peacefully because of limits. Robert Frost summed up this truth when he said, “Good fences make good neighbors.” Even artists, famous for defying limits and living free uninhabited lives, need to adopt some limitations. George Braque, founder with Picasso of Cubism, said that “In art progress does not consist in extension, but in the knowledge of limits.”

Happiness also consists in knowledge of limits. Living by them enriches our relationships, our creativity and gratitude.

The Power of Community

One critical part of happiness, however, is still missing. We have acknowledged the power of acknowledgement. We have delineated the centrality of limits. Now we need to find community. The Christian existential philosopher Soren Kierkegaard used to say, “The door to happiness opens outward.” Life is with other people.

We find community by giving of ourselves. Rabbi Sidney Greenberg told a story I have experienced many times. Around the same time, two women lose their spouses. Both have been married for over 50 years. One responded by isolating yourself. She stayed home. She didn’t go out with friends, to parties, to the symphony. It did not feel right without her husband. The other widow made a decision. She decided to enter a new phase of life. She volunteered. She took classes. She traveled. Rabbi Greenberg ran into her at the hospital, and he could not believe the transformation. She said she could not have survived had she not started giving.

Lighting Candles for Each Other

In a few days we will gather around our family tables for a communal meal. Jewish families will have an additional holiday. Hanukkah. Hanukkah lasts for eight nights, and it follows a particular ritual. A certain candle, called a shaman, or head candle, is used to light the others. We begin the first evening by lighting one candle. We progress each evening, lighting an additional candle. By the eight night the entire menorah is lit up.

A certain candle is used to light all the others. It is called the shamash, the helper candle. The shamash lights each candle. It helps the other candles come to life. Each of us needs a shamash sometimes. We need someone to flicker us back to life, to perk us up when we are down, to give us comfort when we feel sorrow. And each of us can be sham ash to another. We can help, support, kindle the flame of hope when others need it most. That’s how we build community.

May each of our sacred communities—our synagogues and churches—serve as a shamashim to one another. May we nurture one another’s lights, and together give light to our people, our community, our world.

To get free weekly spiritual inspiration from Rabbi Moffic, click here.