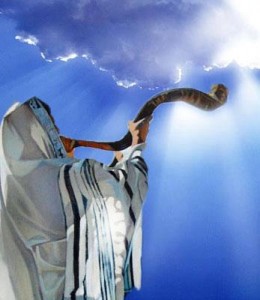

This is the text of the sermon I delivered on the morning of the Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Are You Christian? Get Your Free Jewish Holidays Cheat Sheet.

The most popular musical in the country when I was in college was Rent. Perhaps you saw it. It was not as edgy as, say, the Book of Mormon, but it had its moments.

One of its most popular songs was called “Another Day.” It is a paean to the idea of carpe diem, seize the day. You know the idea. Today is the only day we have. Make the most of it.

Such advice usually comes along with the encouragement to live without any regrets. One verse in the song says,

There’s only us

There’s only this

Forget regret

Or life is yours to miss

“Forget regret?” Is that really possible? Can we really live—make choices, form relationships, do important work—and have no regrets? To explore this question, let us turn to the biblical story we just read.

God asks Abraham to take his son Isaac to the top of a mountain and murder him as a sacrificial offering. Abraham obliges until, at the last moment, an angel stays his hand. A ram is slaughtered in Isaac’s place. Abraham and Isaac leave, and the next passage we read tells of the death of Sarah, Abraham’s wife and Isaac’s mother.

Everyone has regrets

Do you think Abraham regretted his eager and affirmative response to God’s request? After that experience on the mountain, he and Isaac never speak again. Do you think God regretted asking Abraham to prepare to perform such an awful act? Perhaps God expected Abraham to challenge God’s command? Perhaps God regretted giving such a horrible test in the first, in a way a parent might regret encouraging their child to do something that turned out to be way too much?

Did Sarah have regrets? Perhaps she should have stopped Abraham when he left with Isaac to go up the mountain. Earlier she had forced Abraham to expel Hagar and Ishmael from their home. Perhaps she felt she could have at least spoken up and told Abraham he could not, no matter what he thought God was saying, prepare to sacrifice their only son?

And what about Isaac? The commentaries say he was 36 years old when this happened. Now I know in the good old days, children used to obey their parents, at least until they were 18. Today that obeying stops as soon as they learn to speak. But still. At 36 he didn’t stop and say something?? Might he have regretted his acquiesce?

We can make a case that every party in this story regretted their actions. Yet, we still read it every year. We read it on one of our central holidays. We wrestle with its meaning. It is part of our Jewish story, our framework for making sense of God and ourselves.

We are meant to put ourselves in the shoes of Abraham, Isaac, God and Sarah, asking ourselves how we would have responded, and taking those insights and applying them to the choices we are making today. Thus the question: What regrets do we have?

What Regrets Do You Have?

I can start. I regret not spending more time with my grandfather near the end of his life. I regret the times I have gotten upset or spoken rudely to my wife. I regret the times I have not been as understanding of my children as she has been. I regret the times I did not show or express my love and admiration for my parents. I regret the times I have not visited or called people who were sick or in the hospital. I regret the times I did not prepare as diligently as I should for sermons or classes.

I regret the times I did not hear the unspoken pain, the unspoken desires during a conversation. I regret the friendships that fell apart because of I didn’t write or call. I regret the times I did what was easy instead of what was important.

And I also regret the untaken vacations. I regret not staying an extra week or two during our Solel Shabbat weekends in Longboat Key. I regret some of the meals where I didn’t order wine or dessert, especially when someone else was paying.

We all have regrets. Sometimes they are easy to acknowledge. Sometimes they feel impossible to accept. We rationalize. We blame. I’m sure Abraham rationalized his decision. God told me to do it. What choice did I have? The great scientist Richard Feynman once said— the easiest person to fool is yourself.

Stop Fooling Yourself

Today is an opportunity to stop fooling ourselves. The Talmud describes Rosh Hashanah as Yom Harat HaOlam, the day of the creation of the world. Today is pregnant with possibility. The gates of change, of choice, are wide open. We don’t need to rationalize. We don’t need to blame. We need to accept and resolve.

Accepting is hard, especially today, because it is so easy and tempting to compare ourselves to others. Consider Facebook: Someone might share an article proclaiming the top ten things every parent must say to their child—and you look and see, huh, well I’m not measuring up.

Or we see pictures of another family taking their child to the Art Institute followed by the symphony and then closing with an impromptu cooking class. Huh, well I downloaded a new educational game today for the iPad.

Is anybody here a perfect parent or grandparent? Is anyone a perfect brother or sister or son or daughter? The whole idea seems absurd. We make mistakes constantly. We lose our temper, say something we wish we hadn’t said or we don’t respond strongly enough to a situation that needs our response. We could go on and on.

To accept our regrets is not always to condone a choice we made. It is not to pretend we were necessarily right. Rather, it is to accept that the choices we made have made us into the people we are. To accept our regrets is to accept ourselves.

The Hardest Part

This acceptance is the beginning. The harder part comes next. See, Judaism does not urge us to simply accept ourselves and be happy. These holy days—in fact, our whole lives—are times for change, transformation, growth, teshuvah. Rosh Hashanah means the “Head of the Year,” as in the New Year. But the word shanah also means change. In other words, this is the holiday of change.

Acceptance is the first and critical part of change. It is the precondition for what comes next because, as the great psychologist Carl Rogers put: “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.”

How then do we change? How do we become the person we are meant to be? In addition to acceptance, three experiences or feelings can lead us to change.

One is fear. Just think—if you are running in one direction and see a tiger coming at you, you will change directions.

The second is tragedy. If a beloved friend who smokes dies from lung cancer, you might be more likely to give it up. These are important impetuses for change. But we have little control over them. They happen or do not happen.

What Do You Long For?

The last feeling, however, is one we do control. This last impetus—the one that can change us this night—is desire. When we long—we deeply desire—to do something, to be something, to change our ways—we can push ourselves to do so.

The most moving biblical example of this truth is Judah. Judah is the fourth son of Jacob. It is from Judah that we have the term Jew. In fact, all Jews today are descendants—unless you are Cohan and Levite— of the tribe of Judah.

Judah begins his adult life as a jealous and angry brother and son. He leads his brothers in throwing their younger brother Joseph into a pit and then selling him to roving slave traders. Then he seduces his late son’s widow. He certainly is no saint.

Then something happens. Judah sees his father Jacob’s pain at the loss of Joseph. He sees the seeming inability or unwillingness of his brothers to lead or change. He longs for reconciliation, for healing, for family tied together not only by self-interest but by love and caring.

Then, when he and his brothers come before Joseph, whom they do not recognize as the Prime Minister of Egypt, he is the one who leads. He is the one who pleads the needs of their father. He is one who is willing to be taken prisoner instead of his younger brother Benjamin because he knows that Benjamin’s absence would devastate their father.

Judah Persisted

It was certainly not easy for Judah. He probably feared Joseph would kill him. Indeed, the biblical text suggests that when Joseph revealed himself to his brothers, their reaction was not joy or relief. It was utter terror. He was in a position of great power, and they had once made him a slave. Judah, however, persists and changes nonetheless.

What do you long for? That is the key to knowing where you need to change. Do you long for a deeper relationship with your spouse? Do you long to speak again to a brother or sister who hurt you? Do you long to say something to your child without fear of being offended or shut out? Making the change to meet these longings is not easy.

Indeed, we need to long for change enough to get through the huge difficulty it will bring. And we need to resist taking the easy way out. If we don’t, the change will never last.

The Broken Butterfly

Now I’m not a zoologist, so I can’t speak for the scientific accuracy of this example, but I recently read a  piece about a man who came across a butterfly’s cocoon. The cocoon had a little hole in it, and the butterfly was struggling to get through. The man watched as the butterfly struggled for hours. He saw that the butterfly seemed to be making little progress and had gotten as far it could. So the man decided to help out.

piece about a man who came across a butterfly’s cocoon. The cocoon had a little hole in it, and the butterfly was struggling to get through. The man watched as the butterfly struggled for hours. He saw that the butterfly seemed to be making little progress and had gotten as far it could. So the man decided to help out.

He got a pair of scissors and cut away the rest of the cocoon. The butterfly easily emerged and flew out. But its body was swollen and its wings were small and shriveled. The man continued to watch it, thinking that the body would expand and the wings would enlarge naturally to support it. But neither happened. The butterfly never grew into the fully functioning healthy butterfly it was supposed to become. Without struggle, without difficulty, neither will we.

You are not alone

But here’s the most beautiful and most important part—it’s not all up to us. Much of what I’ve said so far—aside from the biblical stories and midrash—we could learn from psychology or literature. That is critically important. But today, here, in this synagogue, I tell you we are not alone in pushing for change.

We have a God, a force, a being larger than ourselves, who knows us, loves us, and desires for us to become the people we long to be. That is why we gather here; that is why we read from this ancient book; that is why this eternal light remains ever burning. God has faith in us.

A student once went to his rabbi with a problem. He said, “Why do we pray on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It doesn’t seem to work. We always sin again. Why do we need to come year after year and apologize when we know the same pattern will just happen over and over.”

In response, the rabbi asked him to turn around and look out of the window behind him. Outside was a toddler learning to walk. “Tell me what you see,” said the rabbi. “A child, standing then falling,” replied the student.

The rabbi told him to come back tomorrow. He did, and the next day and the next day. He saw the same scene: the child standing, falling and standing again. Then at the end of the week, the child stood and didn’t fall. The child’s eyes lit up. He seemed to have achieved the impossible.

The rabbi turned to his student and said, “So it is with us. We may fall again and again, but in the end, a loving God gives us the opportunities we need to stand up.” May this year be one where God helps us stand up, change, and become the person we long to be.