This was one of those films that I like more when I was watching it than when it was over. Which makes sense, considering that’s generally the way of all experiences. I’ll try to put it more clearly: I was taken into its world and fairly charmed  through most of it (until the last twist of events, which struck me as just a little too much), but afterwards it all seemed to shred a bit, like worn tissue.

through most of it (until the last twist of events, which struck me as just a little too much), but afterwards it all seemed to shred a bit, like worn tissue.

I think the best way to look at Lars is as a parable. If you can do that, the difficulties with the premise and with the unrolling story fade a bit.

In short: Lars is a young man living in the garage of his parents’ house – his parents are dead, his mother having died when he was born – and his brother and pregnant sister-in-law live in the main house. Lars is functional – he has some sort of responsible job that requires him to wear a tie and sit at a computer in a cubicle – but he is also disturbed. Deeply anti-social and fearful of human contact, his sister-in-law is deeply concerned to the point of tackling him when he returns home from work one night to force him to come to dinner at their house.

But then one day, Lars appears at their door, smiling and excited. He has a young woman who’s come to visit him. They met online. She’s a missionary from Brazil and very religious so they can’t stay in the same house. Her name is Bianca.

Bianca, of course, is a sex doll.

And so the story proceeds, with the point being that Bianca is serving some purpose in Lars’ delusions and issues. A local physican (Patricia Clarkson) advises that they just sort of go along with what’s happening until it works itself out. She devises a way of meeting with Lars every week – saying that Bianca requires a weekly medical visit – and through these visits, as well as small revelations by Lars’ brother, we begin to discern the source of his problems.

After the natural initial surprise, the small town eventually adapts and pitches in to support Lars by treating Bianca as “real.” And you know what happens to real people…

Yeah, this is where the film lost me a little bit. I could accept almost everything else up to this point, but when the resources of a hospital get involved, some sort of wall was broken for me and I couldn’t buy it, even though I kept telling myself, “Parable. Parable.”

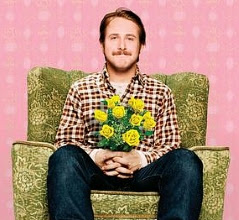

There were a lot of things to like about this film. It’s very humane, very understanding of human nature and flaws. It’s got excellent performances, especially Ryan Gosling as Lars, whose inner turmoil is ever so gently played underneath the surface of his amiability. Bianca held her own.

The portrayal of religion is unswervingly positive – Lars and almost everyone else attends a Lutheran church – peopled by folks who are real, but seem to be seriously trying to follow Christ.

The theme at the core of the film is powerful, and expressed in the minister’s reading of 1 Corinthians at a service: “When I was a child…” Lars is broken inside, we are led to believe, because he never knew a mother’s love and acceptance and his grieving father was emotionally unavailable to him. The symbol of this brokenness is a baby blanket that Lars’ mother made for him before she died and which he wears as a scarf, or has Bianca wear. (although the blanket is in great condition for a 27-year old object, I’d say!) At one point, Lars asks his brother how he knew he was a man, his brother, struggling for words, eventually emerges with the answer that you know you’re an adult – a man – when you think about other people, when you do what’s right even if it costs you.

So there’s all kinds of good stuff in there – and don’t be put off by Bianca’s, er, background. It’s clear that Lars doesn’t use her for that purpose, and it actually works to set off his innocence in a rather powerful way.

My problem, I think, came down to the fact that I could really never understand what Lars’ problem was. It was mental illness, okay, but then the whole childhood-adulthood thread implies something more in the realm of will. The mixed messages diluted the ultimate point, I think, for it is really not right to say that someone who suffers from a mental illness just needs to grow up. You know?

Finally, to keep raining on the parade, I was a little put off by the end. It veered from simple into simplistic, and I find it hard to buy that any sane woman would be interested in a guy she had just watched date a sex doll for six months. But then, that woman had some maturity issues of her own, I suppose, something brought out very intelligently in this commentary, which I think is very good:

Lars’s fantasy, the sensational element of the film, is a massive, audacious absurdity. And the film would not work without it. It is the perfect contrast to Lars’s personality, and in time the rather elementary (but clear and effective) psychological dynamic behind all of this is revealed. It is then we begin to understand that his meekness is, surprisingly, something with a strength of its own and that The Delusion was merely his mind’s way of seeking both healing and an initiation to adulthood.

A central theme of the film deals with what Robert Bly termed “The Sibling Society” in his book by that title. The Lindstrom family history provides an apt illustration for this concept. Lars’s mother died when he was young, and he doesn’t remember her. He and his older brother, Gus (Paul Schneider), grew up in a home with a distant, embittered father. Paul left town as soon as he could, leaving the quiet Lars to rely on their troubled father for his most meaningful relationship. When Gus returned, after the father’s death, he found Lars extremely withdrawn, afraid even to make the most ordinary physical contact with another person. A sibling society is one that has made fair progress toward eliminating hierarchy–leveling the playing ground, establishing absolute egalitarianism. In such a society, parents have no special rights–and no special duties. As a result, children are not initiated into adulthood. After all, who is to say that adulthood, the life of responsibility and difficult commitments, is in any way superior to “sibling life”–in which every person relates to another largely out of self interest? Thus Lars has never, really, grown up. Instead he has remained vulnerable to excessive fantasies, and this simply because he’s never been guided toward anything else. Dysfunction, it must be noted, is the inevitable cost of a prolonged sibling existence. The meek Lars is an exceptional case though, given that by nature he possesses such minimal self interest. And so it is that his dysfunction, as well, manifests as something most exceptional.

One of the roles of The Delusion here, sensational and gaudy as it appears in some lights, is to be the entertaining sweetener of the film, the delicious tension, the spoonful of sugar allowing a fortifying medicine to sneak by without stooping to obvious preachiness. But the message is there–oh yes, it is there. One telling example of the expert blending of humor and substance in the film can be found in the office antics that eddy around Lars whenever we see him at his job. Two of his co-workers, Kurt (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos) and Margo (Kelli Garner), have embellished their workspace the way that many of us today do with, let’s face it, toys: action figures for Kurt, teddy bears for Margo. From time to time, when Kurt or Margo leave their desks, a feud escalates that involves covert kidnappings and minor mutilations. In one of Mr. Gosling’s most charming moments, Lars tries to stop Margo’s tears by performing CPR on a small bear that Kurt had executed by hanging. This subplot is vital to the film, and, tonally, it is absolutely convincing. It feels true to life, but at the same time it cements, with a delicate touch, the notion that Lars exists, day to day, in sibling terrain. And how perfectly this sets up the final moment of the film, in which Lars turns to Margo and suggests that it is time they “catch up” to the others.