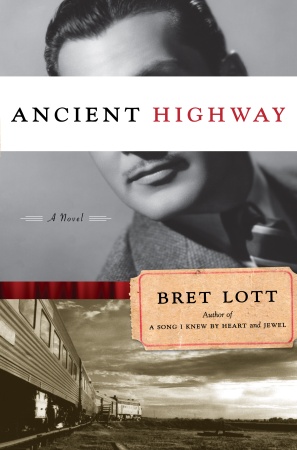

A couple of weeks ago, I read Bret Lott’s newest novel, Ancient Highway. If you don’t know who Bret Lott is, you can read a good introduction to him here, at Jeffrey Overstreet’s site, where Jeffrey reprints a segment of a 2007 interview with Lott (author of, among other books, Jewel, the Oprah Club pick that’s sold the most copies of any so far):

The challenge for a writer who is Christian is going to be the wrestling with himself to see himself as not the center of the universe every power in the world would have us believe we are. And that means showing sin for what it is: the distance we have made between ourselves and God.

We must be able to see that when Christ hung around with the prostitutes, they weren’t the be-robed harlots of a Cecile B. DeMille epic. We must, when we think of Him being with them, see Christ standing next to the prostitute on the corner of any major city in America – the world – waving down johns from cars cruising by slowly, lifting their tops or skirts to entice someone to turn a trick. We have to see Christ as being on a street corner with a meth addict hopping up and down, and see Him in a hotel room with a man and woman who are married to other people, and to see Him in a strip club, or gay bar, or dinner table at which the father slaps his daughter for the tattoo she has gotten – and we must see all of them – all of us – as fallen before Him, as lost, as confused and perplexed and as cursed as anyone in the New or Old Testament.

Somehow we’ve become convinced that we are advanced … that our sins aren’t the sins of those who have come before us, that we know better and that things are different. But they aren’t, and we aren’t.

I am fairly sure that my oldest son read The Hunt Club and liked it a lot. Ancient Highway was the first novel of Lott’s that I’d read.

The story concerns 3 generations: Earl, who runs off from his home in Texas to Hollywood in the 1920’s at the age of 13, his daughter Joan and her son Brad. The tale is essentially about broken dreams and the delusions in which persist in pursuit of those dreams, the collatoral damage of our pursuit and the brokenness of family ties.

It was a decent read, although I wouldn’t say it enthralled me or even intrigued me much. There are a few moments of truly marvelous writing – the first chapters in which we follow Earl as he jumps a train for the West after discovering something intriguing about himself at the bedside of his dying older brother. There’s a memorable scene – to me, the most vivid piece in the book – in which Brad, on board a ship filled with Vietnamese refugees (the novel’s last events occur in 1980), reflecting on his own shattered and non-existent family life, observes a family group that is physically shattered in a number of ways, yet still a family, enjoying, despite their suffering, a shared game in the midst of physical deprivation. It is possible, Brad thinks. Family is possible.

To me, however, in the end, the book’s structure and purpose – to reveal the possibility of reconciliation and beginning again – was a bit too obvious. Objects found at the beginning of the story, the symbols of original discord, reappear at the end as the instruments of reconciliation, predictably. The characters were mostly cyphers to me – I had no idea who Joan was except for a woman who used to be a very hurt little girl, and bore great bitterness toward her parents because of it. I suppose that for the sake of the story that is all I needed to know, but as a consequence, she didn’t feel so much a real person as a name with a few attendant characteristics who served a function in an overall design.

There is a very lengthy scene that takes place at a regularly-held flea market at the Rose Bowl. The aged Earl, who never did make it in the movies after all, sells caftans that he’s made there, and he enlists the recently discharged Brad to assist him. At one point, as tension mounts regarding a piece of information that Earl has withheld from Brad, the latter notes a moment in time when he senses something is happening, and he senses that one of the other eccentric sellers, a woman whom he has learned is suffering from cancer, is praying for him. I note this only because I’m always interested in how writers deal with the spiritual. That whole long scene at the Rose Bowl was, it seems to me, intended to evoke something of what it means to be Church, the Body of Christ, gathering in fellowship, mutual care and even sharing of food and drink. But Brad’s sense that this woman was praying for him came out of the blue – we have no hint before this point that Brad has ever really thought much about religion or the spiritual life, and he evidently was not raised by parent or grandparents to think about these things. I respect what Lott is doing here, but this sudden spiritual realization of someone else’s prayer for him didn’t exactly ring true to me.

So…a few pieces of excellent, moving writing. A plot that was interesting in parts (the sections dealing with Texas and old Hollywood and the beginnings of Earl and Saralee’s relationship),and not so fascinating in others. The novel reveals hopeful moments of reconciliation and forgiveness, but unfortunately, the characters who live them don’t, for the most part, live.