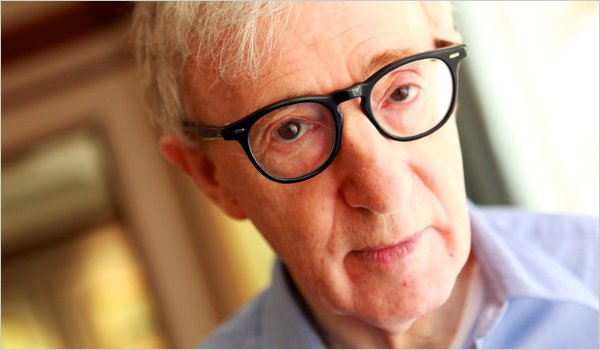

Woody Allen, interviewed by Dave Itzkoff, in today’s New York Times was a bit uncomfortable when wished a happy Jewish New Year by his interviewer, responding “That’s for your people”. However, he went to say some very interesting things about faith and religion.

“To me,” Mr. Allen said, “there’s no real difference between a fortune teller or a fortune cookie and any of the organized religions. They’re all equally valid or invalid, really. And equally helpful.”

Is he wrong or is he right? Of course, the answer is yes. In many ways there are no differences between any of the faiths and practices which help us in our lives, especially in the most significant sense – that they help us. But in other ways, there are profound differences.

Fortune cookies and fortune tellers help only the individual who avails themselves of their respective insights, or is that “insights”? – you decide. The organized religions to which Mr. Allen compares them, should also connect us to things beyond ourselves and our own immediate needs.

It may be God, it may be other people, but when they do their job properly, that too is the work of genuine religion and religious experience. If they are not accomplishing that, if they are not helping us to reach beyond ourselves, then I am with Woody – there is no difference between fortune cookies and faith.

Speaking about his about-to-be-released film, “You Will Meet A Tall Dark Stranger”, Allen commented:

“I was interested in the concept of faith in something. This sounds so bleak when I say it, but we need some delusions to keep us going. And the people who successfully delude themselves seem happier than the people who can’t.”

But are those who believe really deluded? If the faith they have keeps them going and makes them happier, why is not real? Must something be scientifically true to be real? Is love real? Is compassion real?

On this point, I think that it is Mr. Allen who is deluding himself, or at least using pejorative language to soften the blow to his materialist self about the reality of religion. Of course, that’s a motif with which Woody Allen has wrestled for decades.

At the end of Annie Hall, Allen’s character shares the story of a man who tell a psychiatrist about his disturbed brother, an man who thinks he’s a chicken. Asked by the psychiatrist why they don’t get the brother some help, Allen responds that they would, except they need the eggs.

In the end, whether religion is a grand illusion or an image of a far greater reality, if it helps us and helps us to help others, it’s pretty wonderful – in whatever packages it comes.