When Mary Baker Eddy was a young girl, farmers used to bring their sick animals to her for healing. Of course, this was New England in the 1820’s, the birthplace of American transcendentalism. In Russia, Madame Blavatsky was soon to begin expounding her occult-philosophical Theosophy theories and, up the road from Mary, Joseph Smith was digging up a book of golden plates that he would use to found Mormonism. But what the hell? If I was a diarrheic cow, I would have gone to see Mary.

When Mary Baker Eddy was a young girl, farmers used to bring their sick animals to her for healing. Of course, this was New England in the 1820’s, the birthplace of American transcendentalism. In Russia, Madame Blavatsky was soon to begin expounding her occult-philosophical Theosophy theories and, up the road from Mary, Joseph Smith was digging up a book of golden plates that he would use to found Mormonism. But what the hell? If I was a diarrheic cow, I would have gone to see Mary.

A few years later, following an accident, she discovered that she could heal herself and others, too, and soon she was healing neighbors far and wide, just like Jesus did in olden times. Along the way she taught people how to stave off everything from the common cold to cat allergies to breast cancer. Then she fell among “magnetic healers” and hypnotists, sharing notes and developing a system of thought that took on the entire sweep of Western philosophy’s questions about the relationship between mind and body.

Eventually, Mary grew up. Believing that anyone could be taught self-healing powers, she codified her beliefs and compiled them into her 1875 book Science & Health With Key to the Scriptures. Blending mystical wisdom with old school Congregationalism, her teachings find modern correlatives (a favorite Christian Science word) in books and movies ranging from The Power of Positive Thinking to What the Bleep Do We Know? to The Secret. By the time she died, she’d established hundreds of churches and, to date, nine million copies of Science and Health have been sold.

Thus was born the Church of Christ, Scientist, a.k.a. Christian Science. But if you’re looking for lab jackets and, well, the scientific method, you might be disappointed. On the mind-body question, Eddy drove her stake into the ground on the notion that the two are distinctly separate, the mind being a manifestation of God’s spirit. Nothing wrong with that belief (and I’m even willing to believe it myself), but last time I checked, science holds a different view.

The idea, you see, is that the body is matter. And matter is an illusion and therefore evil. That goes for sickness, rashes, broken bones and fibromyalgia, too. The only real reality is that which is spiritual. So, if you get sick, or you break a leg or pop an eardrum, well, you’ve probably been allowing the material world to sort of get in the way of the spiritual. As Eddy put it:

“That matter is substantial or has life and sensation, is one of the false beliefs of mortals, and exists only in a suppositious mortal consciousness. Hence, as we approach Spirit and Truth, we lose the consciousness of matter.”

And:

“Life is, always has been, and ever will be, independent of matter; for Life is God, and man is the idea of God, not formed materially but spiritually, and not subject to decay and dust.”

And:

“How can intelligence dwell in matter when matter is non-intelligent and brain-lobes cannot think? Matter cannot perform the functions of Mind.”

Okayyyyyy.

Usually, I try to avoid discussing theology on this blog. But I thought you might want to know what we walked into this last Sunday. At the Sixth Church of Christ, Scientist, you won’t find a lot of science. You will, however, find loads of history. In fact, from the moment we entered its doors, it was the present world that quickly faded from memory, as if of no more consequence than a soap bubble.

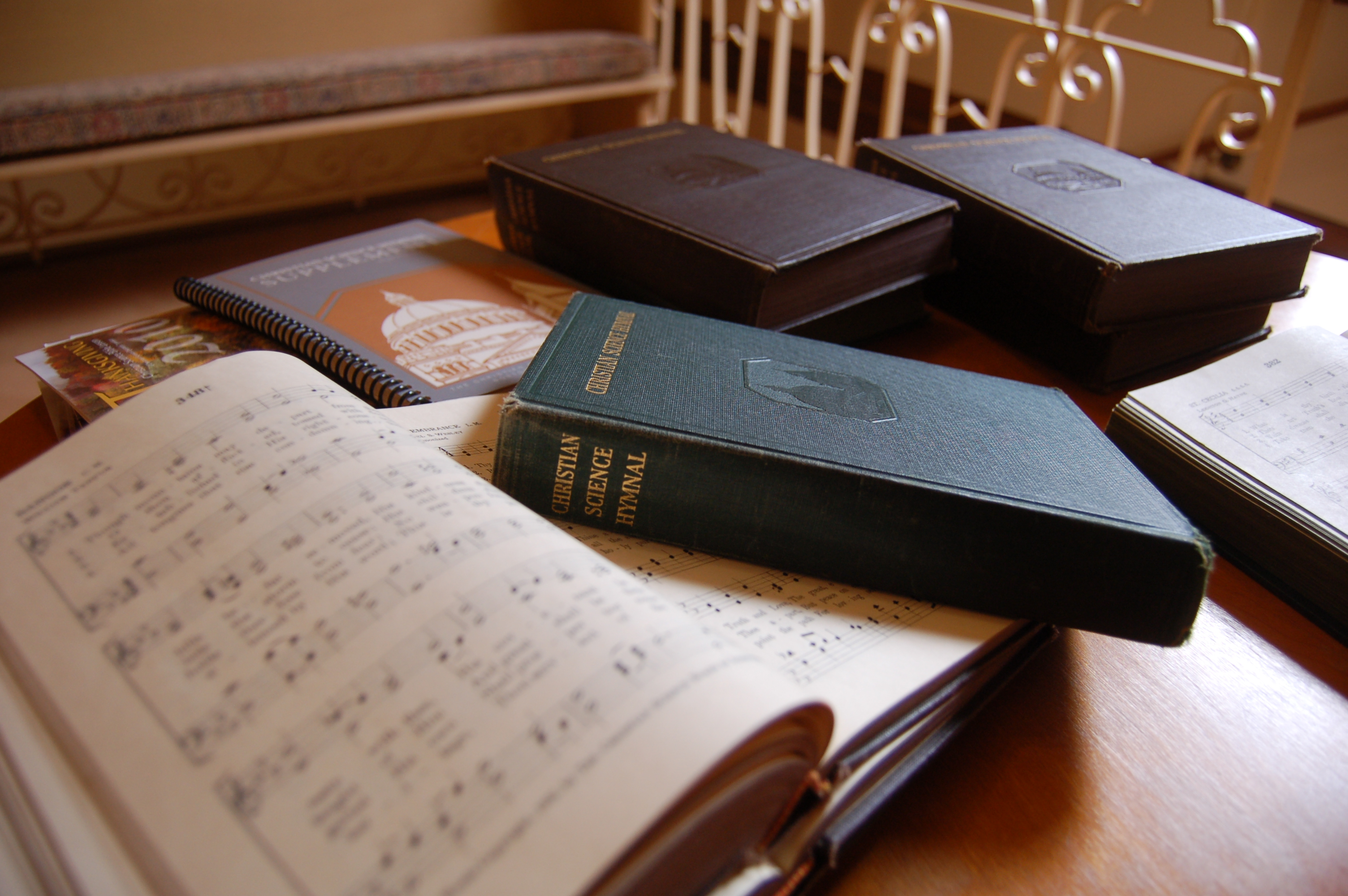

This is a church that hasn’t changed since the day it was built—right down to the threadbare, yellowing hymnals we found scattered about.

Even the members—a scant 12 were in attendance the day we visited—were apparently survivors of the original congregation, grey-headed and doddering in to hear a service that has not been altered by as much as a single word.

Even the members—a scant 12 were in attendance the day we visited—were apparently survivors of the original congregation, grey-headed and doddering in to hear a service that has not been altered by as much as a single word.

If the cavernous church architecture, with its labyrinthine hallways and ornate brickwork had the flavor of a Masonic Lodge, that could be due to the fact that its architect, Morris H. Whitehouse, was a prominent Mason, who patterned the design on the Christian Science Mother Ship Church in Boston. The church has, for years, fended off allegations from wacko conspiracy theorists that Christian Science is an offshoot of Freemasonry. Coincidence? I think not.

The Christian Science service goes something like this: members stand and sing a hymn and then sit as a professionally-trained opera singer belts out a hymn to a piano accompaniment. The massive, 1,990-pipe organ will chime in at some point, performing another hymn. The music is perfect and godly and exactly what Mary Baker Eddy herself would have heard 150 years ago.

Then the readings begin. This part forms the core of the program. Two readers (both women) stand at the pulpit. One reads a passage from the Bible (the King James Version, naturally) and that is followed by the second reader, who recites a “correlative passage” from Science and Health. They go back and forth like that for about an hour. That’s it. No explanation. No sermon. No hallelujahs. No kidding.

As drop-in visitors, we were left scrambling to find the right text and to keep up with the recital. Forget trying to actually comprehend the loping, circular cadence of Eddy’s and William Tyndale’s gospel passages, the experience couldn’t have been dryer if it had been conceived in a dust bowl. Which explains the low head count. The other church members had apparently died of the one ailment that Christian Science can’t cure: boredom.

As drop-in visitors, we were left scrambling to find the right text and to keep up with the recital. Forget trying to actually comprehend the loping, circular cadence of Eddy’s and William Tyndale’s gospel passages, the experience couldn’t have been dryer if it had been conceived in a dust bowl. Which explains the low head count. The other church members had apparently died of the one ailment that Christian Science can’t cure: boredom.

Sunday school was no better. A patient, kind adult reader sat at a low elementary school table and declaimed scriptures at a girl who could only struggle to keep her eyes open. No wonder a new generation hasn’t exactly glommed on to Eddy’s “science.”

Note to self: in the Christian Science community, reading is apparently kind of a big deal.

If there’s any new blood to be found at all here, it probably wandered off the street by accident. The old faithful, reiterating long passages they could probably recite from memory by dint of decades of ritualized repetition sat with their eyes glazed and heads bowed in quiet piety. At least, that’s how the women, who sat somewhat toward the front looked to me. Sitting in the back were the grumpy old men, cantankerously suspicious of doctors and isolated in this women-led community, apparently useful only as doormen and ushers.

Don’t get me wrong. The church building is impressive and handsome, and the teachings have a charming, oddball earnestness. I’m sure that if you apply the principles of Science and Health in your life, you’ll make fewer trips to the doctor. Nevertheless, the church we visited was a relic. It is as perfectly preserved—yet manifestly dead—as a dragonfly entombed in amber.

The service concluded with a rousing organ arrangement of one of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, intended apparently to disperse the congregation with joy and high spirits. But for these octogenarians, wobbling to their feet was about all they could muster.

In 1866, when Eddy first articulated Christian Science, it must have seemed so modern! It was science! “New Thought”! A panacea for all ills, forcing medical doctors, dentists, surgeons and other placebo-peddling snake oil quacks to confess their sins and seek an honest profession! But its time has come and gone. Christian Science has the wistful mien of a prophet who has lived to see the outcome of his predictions, and has outlived his usefulness.

It is Ezekiel in winter.