- This was my childhood Kingdom Hall. Originally it had windows through which I could watch airplanes leaving contrails in the sky during the meeting. Since then, Kingdom Halls have been required to seal up their windows, one of dozens of changes they’ve made over the years to isolate their members from society.

From an early age, my mother groomed me to become a Jehovah’s Witness minister. That means that by age four I was memorizing Bible scriptures; by five I was just as comfortable in a polyester suit as in a pair of shorts; and by six I was on stage explaining to my congregation how desperately those sinful people need God’s forgiveness.

By age 19, I was a member of the headquarters staff in Brooklyn, New York, known among the faithful as Bethel. Even though my factory assignment involved stuffing sheaths of paper into a high speed bookbinding machine, my Bethel status was kind of a big deal back home until, eventually, I returned to Portland where I continued in the full time ministry. Along the way, I got to know Witnesses all over the Northwest—and not much else. My world was wrapped up in Witness culture.

And then, around 2003, I was “disfellowshipped”—a Jehovah’s Witness policy that requires all of your friends and family to shun you—and afterward decided that packs of rabid hyenas couldn’t get me to return. So much for the first 35 years of my life! If you’re curious, you can read all about it at my Ex-JW blog.

The whole reason I’m bringing it up now is so that you can understand why, when Amanda insisted that we attend the Witnesses’ annual Memorial of Christ’s Death—their Most Important Day of the Year—I nearly threw up. I have a few issues around my former faith. Along with that decision came the four stages of grief: Procrastination, Changing the Subject Whenever Amanda Brought the Matter Up, Slamming Down Excessively Strong Cocktails and, finally, Accepting My Destiny.

But not before I negotiated a few ground rules:

- EXTREMELY IMPORTANT: No one must know who I am. We would dress the part of Jehovah’s Witnesses. If anyone knew me, I would be shunned on sight; possibly Amanda too.

- The service we attended would be at an out-of-town congregation. Way out. Like, at least 50 miles away.

- If we were going to do this, we would do it right. I would partake of the bread and wine and Amanda would take pictures for the blog.

- I would not arrive sober.

After scouring the map for non-local congregations, we chose a service in Longview, Washington, a small logging and port town about 50 miles north of Portland. But we got a late start and, with misgivings, I had to settle for Woodland, practically a suburb of Vancouver.

At 7:10, with the prerequisite full moon low in the sky, I called ahead to the local congregation and learned the meeting was to start at 7:30. We were only five minutes away, but I there was some unfinished business. So, after locating the Kingdom Hall, we sped into town, found the nearest tavern, slammed a double something-or-other on the rocks and hurried back to the Kingdom Hall. I wasn’t drunk, but heat from the brandy curling about in my stomach supplied me with, if not courage, at least a sense of equanimity.

And then we walked into the Kingdom Hall—me for the first time in over seven years.

I felt like I had just stepped out of a plane.

Here’s what you can expect if you attend a Witness Memorial: upon entering the building you will be greeted by one cheerful smile after another. Jehovah’s Witnesses are skilled at greeting newcomers and are always genuinely happy to see potential converts. You will be helped to a seat and, following the opening song and prayer, be put through a 45-minute lecture about the value of Jesus’ death and the meaning of the unleavened bread and red wine sitting primly in their K-Mart china on a table at the front of the auditorium.

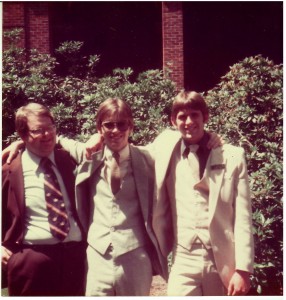

Here’s what actually happened: scanning the crowd for local color, perky breasts and familiar faces, I saw, across the room, someone I had known since my high school days, one of my oldest and dearest friends in the Witness community, Joel Stangeland.

There are about five people in the world whom I definitely did not want to see at that event. Joel is one of them. Our eyes locked the moment I entered the hall. I couldn’t have planned it better. Joel’s presence provided just the right touch: I wanted to take my shot at the Witnesses incognito, but it was better that someone who knew me well would, ahem, witness my public rejection of my old religion.

Most Christian religions commemorate the death of Jesus in one way or another, usually as part of their weekly Sunday service. Jehovah’s Witnesses perform the ritual once per year, more or less on the same day as the Jewish Passover, the day Jesus is said to have died, by passing the unleavened bread and wine from one person to the next like a collection plate.

Of the 18 million or so people worldwide who attend the Memorial each year, only a tiny fraction—11 or 12 thousand—will eat the bread and wine. It’s believed that only those who are going to heaven should do so. The vast majority of Witnesses believe they have an earthbound paradise destiny and hence do not qualify to partake. Thus, as the plates and the goblets are passed, congregants have little else to do but discreetly crane their necks about the hall to see if there are any oddball partakers. I was that oddity.

The talk was presented by special guest Julian Hines, who flew out from Bethel Headquarters for the occasion. If I had hopes that, by reason of his membership in a special religious order, he would deliver an especially insightful, if not moving talk, they were dashed from the moment he took the stage. While he’d clearly worked hard to prepare his talk, he’d overdone it by half, polishing each sentence to a nub, scouring it to remove any remnant of flavor.

All Jehovah’s Witnesses are expected to enroll in their Theocratic Ministry School, a Toastmasters-like program that teaches them poise and public speaking. Evidently, Julian’s lessons were conducted via Speak ‘N’ Spell.

I wish I could say Julian’s arid style was unusual, but it’s not. Because of the special occasion and the presence of visitors (on average, more than half of the audience is made up of non- or lapsed members), Memorial speakers feel tremendous pressure to get each word right. Bethel speakers often feel an additional obligation, knowing they represent the Official Witness Position, as it were. The result, which can often be found at special events and conventions, is a discourse shorn of any spirit or personality—qualities essential to reach, not just the minds, but the hearts of one’s listeners.*

For me, that’s the Witnesses’ crucial missing piece—and, ultimately, one big reason why, upon my unceremonious ouster, I decided not to return. Jehovah’s Witnesses are a conspicuously intellectual religion. Their theology reflects a rigorous, legalistic interpretation of the Bible.** That’s not to say they are always “correct” in their beliefs in my opinion, or even that some of their logic holds water. But they are following a certain train of thought, resulting in an arcane and complex set of precepts. And in so doing they’ve abandoned anything resembling a spirited form of worship. Function has triumphed, leaving form to drown in the shallow water of literalist Bible interpretation.

Didn’t Jesus say we should worship God in “spirit and truth?” I wouldn’t expect the Witnesses to throw a hoedown every Sunday, but as fixated on “the Truth” as they are, their “spirit” is as dry and unyielding as the unleavened wafer of flatbread I nearly broke my teeth on Sunday night. Which brings me to the highlight of the evening—The Partaking of the Emblems.

For over three decades of my life, the Watchtower magazine pounded 1 Corinthians 11:27 into my brain until I could recite it while comatose, if need be: “Whoever eats the loaf or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily will be guilty respecting the body and the blood of the Lord” (New World Translation). Yet, here I was, a former believer—an apostate—sitting with my partner in fornication in a Kingdom Hall in a podunk town in southwest Washington, waiting for my chance to violate this scripture, capture the Kodak moment and post it on the World Wide Web for all to see. The words echoed in my head: GUILTY… GUILTY… GUILTY….

Cognitively, I have as much faith in Witness doctrine as I do in the Easter Bunny. Still, old mental habits die hard.

Following Julian’s recitation of the Meaning of Jesus Death, the charade of passing the bread from one non-partaking audience member to the next began. As kismet (or his own arrangement) would have it, Joel personally handed me the plate to pass along my row. And so my old friend watched as I, my heart bashing away with feelings of guilt and liberation, lifted a chip of unbelievably hard sacramental bread to my lips.

It was like chewing tile. I know it’s just a symbol, but if Jesus’ flesh is this dry and stiff, he isn’t getting enough electrolytes.

I gagged, then coughed, then laughed, the terror replaced by giddy euphoria. I was taking on the Big Guy Himself. So when the wine came around and, while smiling for the camera, a tiny jet of it slipped between my lips and down the front of my custom-made Eton dress shirt, all I can say is that it was worth the price of admission.*** And just in case you’re wondering: the wine itself, while rather innocuous was not unenjoyable, if perhaps a shade too oaky. My guess is, Three Buck Chuck Cabernet 2010.

The deed was done. I’d poked my old god in the ass with a hand-whittled stick. If He exists, He’d better have a good sense of humor.

Clearly, though, Joel didn’t have one. When the ceremony was over and people were milling about, I reached out my hand to greet him. Refusing the handshake, he steeled himself, stepped forward until he was inches from my face and said firmly, “I think you should leave now.”

It was a Ben-Hur moment, two old friends standing face to face, one a Jehovah’s Witness elder, the other now a defector.

My first impulse was to argue the point. This was, after all, a public meeting, in which special efforts had been made to invite all from the community. But I went with my second impulse. “All right. I can respect that.”

Just then, Amanda appeared at my side. Joel’s confrontational attitude vanished and he morphed into a picture of kindness and open-armed hospitality. He cordially introduced himself to her, asked her about the program and inquired about our blog. Locking eyes with her, he all but refused to acknowledge my presence.

I interjected that Joel and I had been friends from way back and he softened for a moment. I mentioned that I have many fond memories of our time together. Stiffly, he told Amanda that he still had some of the poetry that I had written back in high school, specifically, a poem I had written about one of my favorite restaurants. But that was it—and I’m sure even that interaction left him feeling compromised.****

Joel’s shunning treatment hurt. Still, it was the law of reciprocity at work: I’d pissed on his god and he pissed back. If I was dismayed by his two-faced behavior, he was offended by my irreverence.

There is more to him than that five minute encounter would reveal. Joel is a kind, thoughtful, intelligent person who, in my experience, has been a cool-headed, moderating force around other stronger personalities. I miss his mildly sardonic, self-effacing wit and readiness to offer praise and encouragement. In shunning me, he believed that he was doing the right thing. I can understand his ire, and his behavior is easy to forgive. There is every reason to hope that, if only in private, he can do the same for me.

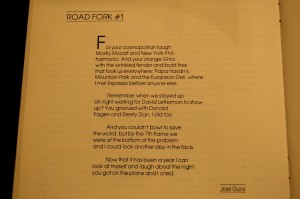

Titled “Road Fork #1,”***** the poem that Joel kept after all these years is a farewell I’d written to my best friend at the time, Phil Weber, who had moved to Bethel. Two years later, I followed him there, and a year or so after that, Joel joined me in New York as well. We know how that turned out: twenty-odd years later, I have enough road forks to fill a silverware drawer.

And Joel still has that poem.

——–

*I’m reminded of a quip often attributed to the third President of the Watchtower Society, Nathan Knorr: “If you don’t put fire into your talk, put your talk in the fire.”

** On the plus side, that literalistic thinking has led them to conclude—correctly, in my opinion—that the Biblical name of God in English is Jehovah, and they have “restored” it to its rightful place in over 6,000 Bible verses, where other Bibles use the less specific term “God” or “LORD.” On the other hand, that same impulse, unchecked, has also moved them to create a Talmud-like code of conduct governing everything from dress and grooming to music selection to how to stand during prayer at their meetings. It includes a list of at least 38 offenses for which one can be shunned from the congregation, ranging from gambling and smoking (neither of which are directly described, not to say censured in the Bible) to the usual vices of adultery, homosexuality, etc. You can read more about them here.

***Does that mean my shirt is now anointed?

****To be fair, the Witness doctrine of disfellowshipping is based on their interpretation of certain scriptures, so they have something of a Biblical basis for their practice. But what of their claim that it is a “loving provision” intended to move sinners to repent? Only in an Orwellian universe can shunning be called an act of love. While about one third of Disfellowshipped Witnesses seek reinstatement, the rest move on with their lives. Some who leave Jehovah’s Witnesses have felt the need to flee by moving to another area, or they try to quietly drop off the congregation radar just to avoid the public shaming and ostracism. Others, traumatized by the judicial action have been plunged into depression and have attempted suicide. Disfellowshipping is a ritualized hate crime.