All right. I admit it. I blew the experiment. Normally, Amanda and I try to reach out to church officials to let them know that we’ll be visiting their service. But this time around, we felt that if we wanted to get the people at the Portland chapter of the Church of Scientology to talk candidly, it would be best to go stealth. Maybe we’d catch them channeling Dictator Xenu or something.

So, as far as Sunday’s Scientologists were concerned, we were just two average people off the street, looking for a new religion—albeit two people nursing a hangover following the previous night’s debauchery. The idea was to smile and nod and go along with everything they told us. To keep them talking, you see.

According to a recent article in the Daily Journal of Commerce, the “Portland chapter of the Church of Scientology claims about 1,200 members in Oregon and Southwest Washington.” Those numbers, however, may be somewhat inflated. Their recent decision to move into the historic Sherlock Building at 309 SW Third Avenue (current home to Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse) hinged on their need for only a 250-seat chapel.

As it happened, the Sunday service was canceled. So it was just us, hosted by a Burger King refugee named Emily, who whooshed us into a small, sparsely decorated office with a mahogany veneer desk and matching bookcase filled with Scientology literature. We could have been visiting an accountant or the sales office of an Infiniti dealership. Seeming to relish her time in a real office, Emily slid behind the desk and invited us to take a seat and began to introduce us to the church and answer any questions we might have. At least, that was the idea. What actually transpired was a probing inquiry into the “real” purpose of our visit. It went something like:

Emily: How did you hear about the Church of Scientology?

Joel: I’ve lived in Portland most of my life…. It’s just something I’ve always known about.

Emily: So, why are you here?

Joel: Oh, you know, we’re doing the church tour. We’ve visited all sorts of churches in the last few weeks and now we’re at your place.

Emily: Uh huh. What do you know about us?

Joel: Not much. Your founder is L. Ron Hubbard…. You have a book called Dianetics…. Um….

Emily: Anything else?

Joel: Not really….

Emily: Have you heard any stories about us?

Joel: Uh….

Emily: (Rolling her eyes) Like, we’re into aliens and UFOs?

Joel: (Laughing with her, conspiratorially) Yeah, sure.

Emily: Okay… um… what do you do for work?

Joel: I’m a writer. I work in advertising and brand development.

Emily: (Silence)

Amanda: I’m a writer, too. And I work in financial planning.

Emily: (Suspiciously)What do you write about?

Joel: Oh, you know, advertising and marketing. I have a few clients and a couple of agencies I work with.

Amanda: I have a blog. People read it.

Emily: (After pausing) So, what else do you know or have heard about us?

Joel: Look, we’re on a church tour. That’s all. We’re just here to today to see what you have to offer. Is that all right?

Finally, she let the matter go and gave us a brief rundown of the church mission, which aims to transform lives by teaching people how to better handle tough situations, difficult people and life itself. The emphasis seemed to be that if your life is broken through alcoholism or a bad marriage, you will get it fixed here. Fair enough. Though it would seem that if you already have your act more or less together, Scientology may not be the right fit for you.

And that’s when I blew the experiment. Emily trotted out a statistic. Stating it as if it were a known fact—and a key article of Scientology faith—she asserted that that 20 percent of the people in the world are “antisocial” and actively injure the other 80 percent. I couldn’t let that slide. “Really?” I asked. “20 percent?” Not in my experience. We’re all hurtful at times, but of those people who are committed to a hurtful way of life, I’d peg it at 5 percent. 10, max. Maybe I just go through the world with rose-colored glasses, but Hubbard’s arbitrary 80/20 rule didn’t exactly resonate with me. We argued about that for a while, I guess, and by the end, she knew we were a waste of time—if not part of that injurious 20 percent.

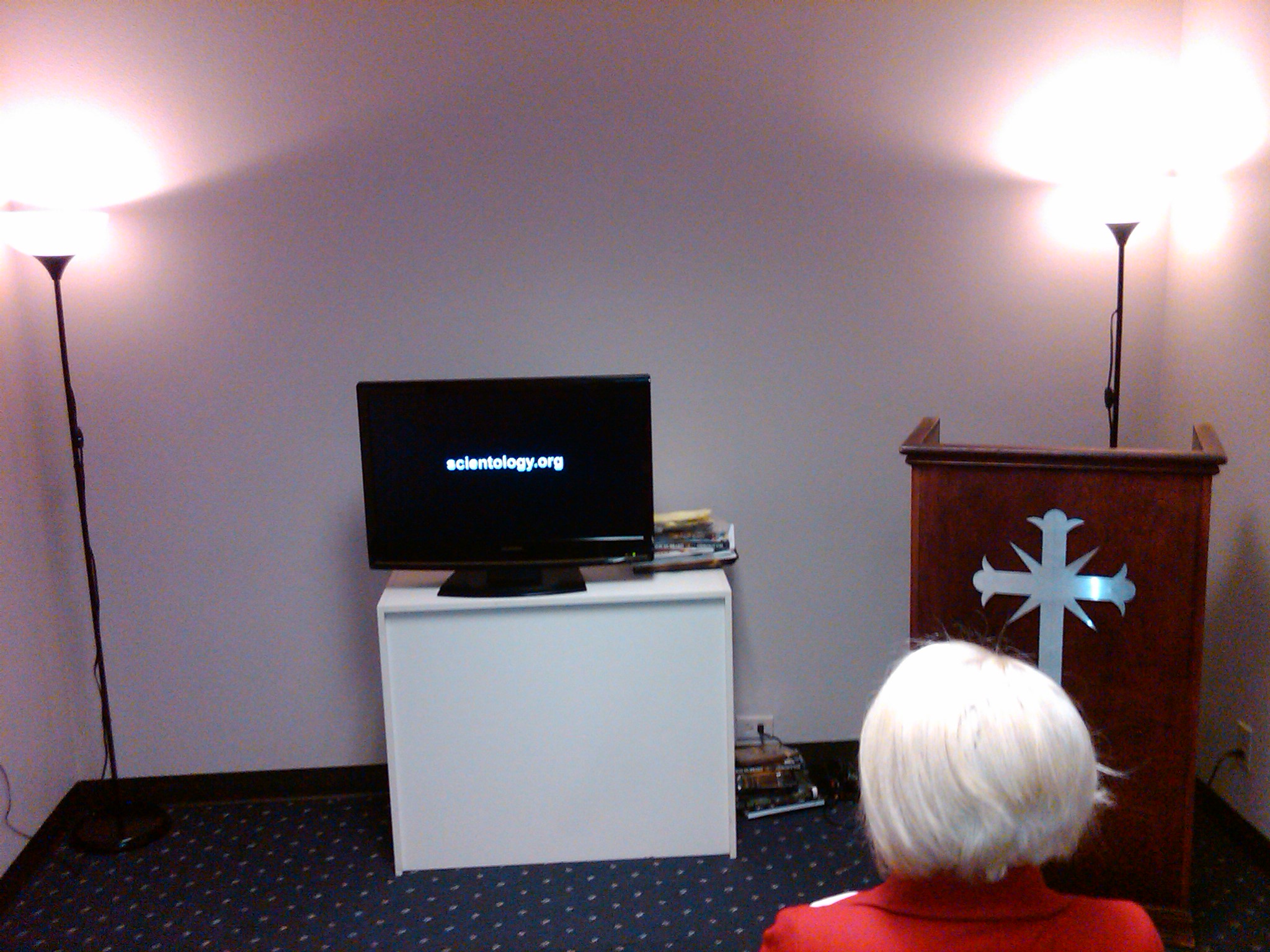

With that, she walked us into another small room barely large enough to hold three office chairs, a wooden pulpit and a video monitor. After rummaging around the back of the pulpit for a few moments, she reappeared with a tin cross and affixed it to a hook on the front of the wooden structure.

After taking a moment to explain to us that the cross she’d hung up wasn’t actually a cross, she popped a DVD into the player and left us alone, to our own devices.

Turns out, the Scientology video booth isn’t a bad place for a make-out session.

When the video was over, Amanda straightened her hair and we stepped back out into the lobby. Emily had vanished, and we were at a loss what to do next. A woman approached, handed us a brochure and thanked us for coming. Then she turned on her heels and walked away. That was it. The Scientologists were through with us. That was when I knew for sure that I’d blown the experiment.

So, left alone again, Amanda and I wandered around the lobby for a minute. Emily had also told us that each church of Scientology keeps an office just for Hubbard, even though he’s been dead since, you know, 1986.

Just as we were trying to capture a camera-phone picture of Hubbard’s head, rendered as an oversized bronze bust, Mick, Emily’s husband, showed up.

While Emily was merely suspicious of us, Mick was openly defensive—even occasionally belligerent. Oozing paranoia, he complained about the travails Scientology has suffered, claiming that the American Medical Association tried to suppress Hubbard’s literature back in the 1950s, because its revolutionary health teachings threatened the medical establishment’s livelihood.

“Basically, the AMA bought off his publishers and editors” and paid them to dilute his teachings so that they wouldn’t be effective for improving people’s health, he said.

“So, what you’re saying is, L. Ron Hubbard’s publisher, who stood to make a fortune, actually had an agenda to suppress his work?

“Yes.”

“But what about Christian Science and other faith healers? Why hasn’t the AMA try to stop them?”

“They weren’t worth the time.”

“Do you really think that’s how the world works?”

“Yes, of course. Why do you think JFK was killed?”

Riiiiiiiiiiight. And, maybe, if we work at it, we can get Dawson charged with the Kennedy assassination.*

While we’re on the subject of conspiracy theories, I should add that it’s hard to talk about Scientology without mentioning its goofball theology. But I’m going to try to avoid that because (a) you’ve probably heard those stories yourself already and (b) I think that’s a distraction. After all, which is weirder: believing that 75 million years ago the Galactic Confederacy dictator Xenu scattered billions of poor Thetan souls around Earth’s volcanos or believing that Jehovah once flooded the entire planet because our ancestors’ parties were getting too loud? If we’re truly honest with ourselves, the Scientologists don’t exactly have a monopoly on weird beliefs.

L. Ron Hubbard’s books make for a terrible history lesson. But as metaphor, they’re all right. Getting caught up in the science fiction aspects of Scientology is like attending a Catholic Mass and ridiculing the doctrine of transubstantiation. Do so if you must (and I often do myself), but remember that there’s a risk of missing the bigger point.

Here’s that bigger point: from its cavalier appropriation of Christianity’s sacred symbol to its use of the polygraph-like E-Meter, which, they claim, indicates whether or not a person has been relieved from the spiritual baggage of his or her past, Scientology is a made-up religion. It’s proof that anyone with an imagination can smoke a bowl, solemnly repeat his or her “insights” enough times—and voila!—get a following. There really is a sucker born every minute.

Strip away all of the frippery that has earned Scientology its cultish reputation, and what do you have? Not much. The notorious Celebrity Centre notwithstanding, Scientology’s theology is not ready for prime time.

But still. If a science fiction writer goes through a mid-life career change and declares all his subsequent work to be religious fact, what of it? And if his theology can barely stand up under even casual scrutiny, rendering it believable only to a gullible minority, who cares? Dumb people need religion too.

Like any religion, Scientology offers some value. It includes accurate psychology that leads to a measure of self-awareness and blends that with pseudo-science and third eye mysticism. Though its benefits are promised to be somehow qualitatively different from any other religion, I didn’t see anything that you can’t get in a good mix of psychotherapy and, say, Buddhism. When I asked Mick about that, he said that the advanced stuff comes later.

I guess Tom Cruise’s “Phheeeeeeeeeew!!” aspects of Scientology got left out of the introductory sales pitch.

The real question for me is: What is Scientology doing for its people?

For one, it gives those who may not have much else going on in their lives a feeling of belonging. Its ’20 percent of the world is out to get you’ mentality appeals to people who may have been taken advantage of and gives them an object to which they can direct their anger and a (pseudo-)explanation for their sense of victimhood. If you’re a Hollywood actor subject to the whims of a fickle media and a capricious industry, Scientology gives you sense of control and empowerment. It also makes you feel smart—a plus for many actors.

Appealing to the ego, an introductory video at scientology.org promises that “you will find your own answers to life’s questions; your own truths about your life and you…. for the subject of Scientology is you.” While it may do that to some extent, it adds in paranoia, mistrust of those outside the faith community and the delusion that your intelligence has magically grown, when, in fact, it has not.

*Tom Cruise in A Few Good Men.