If you’re a man or woman “of a certain age,” you probably associate the Hare Krishna religion with your local airport. Once upon a time you could find them proselytizing—or, if that failed, accepting donations—as people got off the plane. They don’t do that so much any more.

In fact, the Hare Krishnas have changed quite a bit over the last few decades. Once synonymous with hardcore cultism—allegations of kidnapping, brainwashing and child abuse continue to dog them—they were often mentioned in the same breath as Scientologists, Moonies and other cults that flourished in the 1970s and 80s. While at least some of those rumors turned out to be true, the Hare Krishnas have since cleaned up the more egregiously culty parts of their act.

Founded in 1966 and known officially known as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (see also: its Pentagon-ready acronym, ISKCON), Hare Krishnas claim to be just another sect of Hinduism. Like most Hindu faiths, their holy book is the Sanskrit-language Bhagavad Gita. Unlike other Hindus, however, they have their own translation made by their founder, His Divine Grace (But Not in a Cross-Dresser Kind of Way) Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhubada, and called Bhagavad Gita As It Is. Curiously, he came out with this version shortly after God “called” him to leave India to spread his unique teachings in the United States.

Bhagavad Gita As It Is departs from other translations in this key area: it elevates the god Krishna to that of the Supreme Deity. Thus, while most Hindu sects worship an array of gods, all of which are more or less equal, the Hare Krishnas worship only Krishna. Think of them as monotheistic Hindus—an Eastern religion custom tailored for an American audience.

That appended subtitle—As It Is—denotes that this version of the Bhagavad Gita is (in their humble opinion) a superior and more accurate translation. It may be. All I know is, when I see Christian religious sects trotting out their own translation of the Bible, I pick up the back-alley scent of a crooked theological shell game. Yes, Jehovah’s Witnesses, I’m looking at you.

On the other hand, when I see religious leaders being “called” by their Deity of Choice to leave their homeland far, far away so that they can spread their unique word to Godless Americans, I can’t help but cast a knowing glance at Mormon mythology.

If that religious group happens to be Hindu, you’ll forgive me if I roll my eyes in the general direction of the followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

Let’s just say that our visit to the Hare Krishnas last Sunday activated a blip on my cult-dar.

Not that this sign outside their church didn’t:

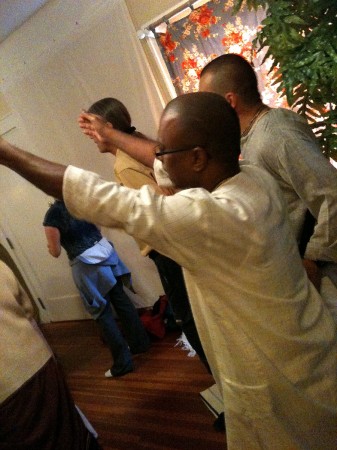

The Hare Krishnas apparently sing their theme song every chance they get, which makes their worship services a lot like a party where the guests sing “Happy Birthday to You” for, like, an hour straight. Except that even Chuck E. Cheese knows not to hand out finger cymbals to every kid in the pizza parlor.

Entering the the living room, we were warmly welcomed by the host, an elderly man in flowing linen robes and a shaved head offset by luxuriant sprays of fur growing out of each ear. Others filed in, until about 20 or so people were crammed into the living room in a blend of (white) Americans and (brown) immigrants. Most wore traditional linen robes and everyone bore a distinctive tilak—a painted-on mark on the forehead and nose—in the shape of a holy tulsi leaf. (Each sect of Hinduism is distinguished by its unique tilak.)

Once the chanting and the finger cymbals set in, they didn’t stop for the next 45 minutes, swaying back and forth and singing the same words over and over without letup. I guess their chant is a pretty big deal. Says His Divine (and Fabulous) Grace, “The transcendental vibration established by the chanting of Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare is the sublime method of reviving our Krsna consciousness…. No other means of spiritual realization, therefore, is as effective in this age as chanting the maha-mantra.”

You see that a lot in Eastern Religions. While ISKCONers promote their “maha-mantra” as the best chant, other Hindus insist that the “Om” mantra is the Vibration of the Supreme. For a Westerner like me, that can be a bit confusing. Which one is the real Supreme? I’m putting my money on Diana Ross.

I’m only half-joking. If singing the Hare Krishna song gets your metaphysical rocks off, go for it. But who’s to say that the opening lines to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony or Rush’s “Tom Sawyer” aren’t just as useful portals to the transcendent? “Love and Happiness” is so primally deep that even Al Green isn’t sure whether he’s a priest or a pop star. And if he hasn’t tapped into the rhythm of Life Itself, how else do you explain all those children conceived to the pulse of “I’m Still in Love with You”?

Among the many places where I part company with the Hare Krishnas is the idea that, if their little ditty doesn’t do it for me, I’m S.O.L. Continues His Absolutely Ravishing (and Divine) Grace:

“Of course, for one who is too entangled in material life, it takes a little more time to come to the standard point, but even such a materially engrossed man is raised to the spiritual platform very quickly.”

After nearly an hour of that infernal chanting, the only thing that got elevated was my tinnitus. I guess I’m too “entangled” to dig this vibe. Now, I’m okay with a religion being excited about whatever it has to offer. But who are they to dismiss as spiritually lesser-than those who don’t share their special groovy groove?

Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

Back in the day, “devotees” (in this group the word is pronounced de-VOH-tee and half-rhymes with “pierogi.”) were expected to withdraw from society and live a monastic life in one of their many temples around the world. It was during that period that Hare Krishnas piqued the interest of cult watchers. Then, in the 1980s, the movement endured a mass exodus due to a series of financial and sexual scandals. Out of those trials, a leaner, more mainstream religion emerged.

In America, a large portion of devotees have immigrated from India and Pakistan, who are attracted to the religion less for its unique teachings than for its resemblance to the Hindu faith tradition they grew up with. For them, it’s a religion of convenience. According to The Sociological Quarterly (Winter, 2008), “Indian immigration has provided ISKCON with new resources and a new target population for conversion.” For what it’s worth, probably half of the people we observed last Sunday were of Indian descent. My observation was that, as is typical in many import religions, these individuals were less fanatical in their worship than their Caucasion counterparts.

That’s not to say their cliquish roots don’t show. After the incessant chanting was finally finished, we sat down for a slide presentation by Jean Griesser, a.k.a. Visakha Dasi, who was in town to sell her book, Harmony and the Bhagavad-gita: Lessons from a Life-Changing Move to the Wilderness.

She and her family had moved from Los Angeles to rural British Columbia to live off the grid in a self-contained “Krishna-conscious community,” complete with its own one-room K-through-12 schoolhouse and temple. This sparked an interesting discussion with with the devotees. “Do your children listen to iPods?” one asked. “Yes, they run around all over the place with those things in their ears,” she said, as if to emphasize the normalcy of their life. Then, deftly cutting the counter-cultural cake both ways, she added that the music they played was exclusively Krishna tunes. Whew. Wouldn’t want their Junior Krishnateers mixing their biodynamically-farmed green beans with the Black Eyed Peas.

Their farm life does indeed seem idyllic. But when Griesser, a.k.a. Dasi, started in on the evils of urban life and modern media while extolling the merits of her solar-fueled fairyland as a place where her children “could grow up around devotees, free from distractions like television,” I had to call bull-puckey. Especially when she flashed a slide that quoted His Naughty, Naughty (But Oh, So Divine) Grace: “Material or spiritual, everything is in harmony. That is God’s law. Everything is in harmony.”

Atheist though I am, I happen to believe that statement is true. And so doesn’t that logically include Los Angeles traffic and its crime statistics, not to mention its vibrant arts community as part of the “everything” that is in “harmony”? For me, the operative word in that sentence is everything and it seems to be the one word she doesn’t grasp. I wish I’d written down her exact words, but her basic point was that cities are less-spiritual places to be than the countryside—just as people outside the Krishna community are pitifully misguided materialists who have poor taste in liturgical music.

As it happened, their flight from the city was no pic-a-nic at Jellystone Park. Summers were plagued with mosquitoes and bears, while the winters were bitter and harsh. One year, they watched a forest fire lick at the fringes of their property. They’d traded the rats of Los Angeles for infestations of field mice. Even the crime they’d tried to escape followed them: a neighbor youth broke into their home and robbed it. In her book, each of these hardships was turned into a Krishna-positive object lesson that enlightened Greisser’s spiritual journey, but it seems to me that the real lesson she should have learned, but didn’t, is that they could just as well have stayed put in Los Angeles and learned the same things. So it serves her right that she landed in Happy Clappy Valley just in time to start running from the neighbor’s attack dog.

And that’s the issue I have with many “seekers” like her. They travel halfway around the world to camp out in communes and ashrams and temples, because somehow that will bring them closer to God or Nirvana or whatever. Blissed out on self-righteous piety, they occasionally return to civilization just long enough to make the gullible jealous of their “enlightened” lifestyle. Chasing reality around the globe, they end up running from it. They could save themselves a lot of trouble and pop a DVD of Wizard of Oz into their evil TVs and give it their Mindful Attention, because if you want enlightenment, you need look no further than your own back yard.

After the service ended and we’d enjoyed the free—and delicious!—vegetarian meal we’d come for, I caught up with one of the local devotees, whom I’ll call Daitya. I asked him whether or to what extent his circle of friends extended outside the church. He said he had a few non-Krishna friends when he was younger, but, with newborn baby, he and his family just don’t go out much any more.

“Besides,” he said, “I can’t smoke, I can’t drink and I can’t gamble. What else is there to do?”

Um, really? I suggested, just for starters, that he could have run the Portland Marathon that day, but I don’t think he heard me.

After the service was over we headed to SamAndTerryAndSophie’s lovely home to debrief the experience. To get to there, we drove down 82nd Avenue, a business district peppered with used car lots and ramshackle porn shops. The kind of neighborhood the Krishna conscious might reject as “too worldly.” But this time we looked again. We drove by a Slavic megachurch and made a mental note to drop in some Sunday. There was a Hispanic-American-owned body shop. We passed Mexican, Thai and Vietnamese restaurants whose dowdy exteriors promised culinary fireworks inside. There is more life along that shabby stretch than you can shake an organic carrot at. There might even be room for a vegetarian Krishna restaurant. I’d eat there. And then I’d go downtown to walk it off and listen to the homeless lunatics teach me the meaning of life.