People usually join a religion for one primary reason: to find answers to life’s most nagging questions. Who is God? Where do we go when we die? How heavy can our make-out sessions get before it’s called fornication? Each denomination may have a different answer to those questions, but one thing remains the same: they all have all the answers. And if you don’t know the right one, too bad for you because you’re going to hell. (Which makes me wonder what will become of me: I’m not even sure I’m asking the right questions.)

And then there’s Judaism—at least the branch of Reform Judaism Amanda and I observed, along with our friends Rachel and Ben (she’s an atheist, but ethnically Jewish; he’s a full-on goy), who’d tagged along with us at Congregation Beth Israel at last Friday’s Shabbat, or, Sabbath, Service.

Judaism is a religion in which questions—not answers—form the warp and woof of faith. In fact, Judaism maintains that the truth about God is unknowable. But, lest one become bogged down in the pulpy morass of relativism, claiming that there are no absolute truths, Jews believe that such truth exists. It’s just extremely difficult, if not impossible, to ascertain. But that hasn’t stopped them from taking on the Sisyphean task of trying. For them, asking questions—cross examining God—is an act of worship. How different from the fundamentalist Christianity’s “this I know because the Bible tells me so” blather.

How different from the religion I grew up in.

Because of that, I suppose, last Friday, I nearly fell in love.

Here’s some self-disclosure. My disfellowshipping from the Jehovah’s Witnesses provided me with just enough distance to look at my beliefs objectively for the first time in my life. To call what resulted a loss of faith is a gross misunderstatement. My entire sense of self and identity was creamed against a wall of disillusionment. For a while there, I couldn’t trust the very ground under my feet. I’d go to the store and take 15 minutes to decide which orange juice to buy for breakfast. I’m not sure, but that could be what a nervous breakdown looks like.

Regardless, I’d gone to bed on Monday with all life’s answers neatly tucked away and woke up on Tuesday to discover they’d vanished.

That was eight years ago. I still don’t have any answers, but it appears fairly certain that my job since then has been to learn how to sit still with the anxiety of not knowing. I’ve found that it helps to remember to breathe.

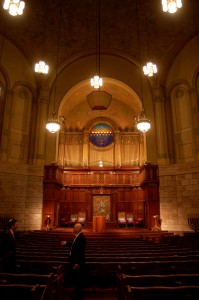

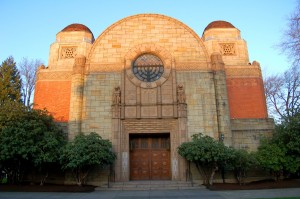

- Walking up the driveway to the synagogue. Pictured here, Ben, Rachel, Rabbi Cahana and yours truly. I’d driven by the 80-plus-year-old edifice hundreds of times. Its massive dome dominates the neighborhood, and as one of only a few Jewish places of worship in Portland, and by far its most opulent, it looms exotic and portentous. One of the fringe benefits of this Year of Sundays project is that it gives me an excuse to go into such places of worship.

Nobody grinds with more tenacity over such existential questions as “Who am I?” or “What does God want from me?” as do the Jews. Such chewing on life’s persistent questions is more than a national pastime.* It’s in their DNA. Quite literally.

According to the book of Genesis, the Hebrew patriarch Jacob spent an entire night wrestling with an angel (nothing homoerotic about that fable!). As morning ascended, the angel rewarded Jacob’s chutzpah by wounding him in the thigh and changing his name to Israel, meaning “God struggles.” Thus the die was cast for all of his offspring—the Jewish people—to contend with God over their fate and to grapple with each other over precise interpretations of their holy texts.

It doesn’t matter whether or not Jacob’s fabled wrestling bout is a historical actuality. What does matter is that one national group has woven its identity around that story so tightly that it has been made true after the fact.

As a good little Jehovah’s Witness, I learned the story of Jacob and the angel at a very young age. I knew early on what the name Israel meant. Also, like anyone who has seen Fiddler on the Roof, I’m aware of the Jews’ uniquely familiar relationship with Yahweh—a side effect of their 3,000-year-old wrestling match with Him.** That close, contentious bond is both a blessing and a curse. As Fiddler‘s battle-weary Tevye complained in a roadside conversation with Yahweh: “I know, I know. We are your chosen people. But, once in a while, can’t you choose someone else?”

The strange thing is, I don’t recall ever learning from the Witnesses the connection between the great Jewish struggle and the story of Jacob. Why? Because it wasn’t relevant to their particular dogma that views Old Testament prophecies as applying to themselves in the years 1914-1922. (Don’t ask.) That oversight is kind of a big deal. I’m indignant.

And that’s just one of many points I didn’t learn about the Old Testament, but which are common knowledge among practicing Jews. Last Friday, it hit me like a wheelbarrowfull of lox and bagels: if you want to really understand what the Bible is all about (at least its Hebrew scriptures) you can do no better than to go see the people who wrote it.***

The Old Testament is the Jews’ story. It belongs to them and most Christian theologians are little more than intellectual carpetbaggers, squatting on foreign narrative territory. I’m coming to believe that a lot of the hurtfulness of Christian fundamentalism is a consequence of the hubris that has resulted from forgetting that basic fact. It has bred militant nationalism and, ironically, anti-Semitism.****

By contrast, Reform Jews are a remarkably peace-loving group of people. The mission statement of Congregation Beth Israel-Portland declares, in part, “We are dedicated to improving our World through Education, Leadership and Inspiration [and] promoting Traditional Jewish Values of Respect, Justice and Compassion.”

Like Catholicism, the Reform Jewish service is replete with tradition and rituals. For instance, in remembrance of their ancestors’ emancipation from their seven-day workweek while they were in slavery in Egypt, the Sabbath is welcomed like a cherished bride. Thus, Friday’s service began with a rousing rendition of a 16th century sabbath song, “L’chah Dodi,” sung in Hebrew:

L’Chah dodi likrat kalah / p’nei Shabbat n’kab’lah!

Beloved, come to meet the bride; beloved, come to meet Shabbat!

At a stopping point in the song, Rabbi Cahana directed the congregation to its feet: “Please rise and turn to the door,” he said. “We are welcoming the bride of Shabbat into our community. Let’s welcome. Let’s embrace. Let’s rejoice with Shabbat.”

And so we turned toward the door at the rear of the chapel, which, as prescribed by tradition, faces westward, to welcome the Sabbath Bride.

It felt a little weird to stand and gaze out into the hallway, welcoming an imaginary visitor into the room. The moment would have been more suggestive if we’d had a clear view of the setting sun. Still, this gesture was a great expression of ritual and age-old tradition—a sort of toast to the setting sun and the onset of the day of rest. And the rabbi made sure to suffuse it with intellectual meaning and emotional value. In other words, with his guidance, the moment hit all four flavor points on the tongue. He continued:

“Oh, I’ve been waiting for Shabbat. I don’t know about you, but needing that sense of holiness that comes to us during this time; needing that sense of separation from the week to come into something that is very special—I’m so pleased that we can be together on this beautiful shabbat. We’re getting glimpses of spring. Enjoying that and the beauty that surrounds us on the outside, we bring that beauty inside of this sanctuary and lift up our hearts and our voices together.”

Question: is he that eloquent every week?

In Judaism’s mindset, everything—from a spring bud to a child’s smile to an obscure snippet of the Torah—is significant. They’ve made seeking out the value of such details their life’s work. Which explains why some of the best books about Buddhism have been written by Jews: both traditions share the common denominator of intensely concentrated mindfulness.*****

After the service ended, we buttonholed Rabbi Cahana.

“We don’t have all the answers,” he said. As humans, “it’s our job to search for meaning. We don’t have the answers for the world, but only for ourselves.”

It’s hard to describe how appealing that sounds. “We don’t have all the answers”? And you’re okay with that?! Your God has the ego strength to not only tolerate, but thrive on debate and dissent? I didn’t know if I’d just discovered Utopia or crack.

Cahana went on seducing me. “Our intellect is a very special gift. How are we going to use it? To take the intellect and turn it into blind obedience would be a waste. So we have to keep struggling to figure it out.” “It” being life and one’s destiny.

And, of course, the Torah.

Somehow we got on the subject of the Kabbalah. Forget everything you’ve heard about Madonna, numerology, Umberto Eco’s novels or some secret mystical conspiracy cult. You can go there if you want, but, basically, the Kabbalah involves study of the scriptures to find out their deeper secrets.

As Cahana describes it, study of the Torah can be divided into four levels of interpretation, each one deeper than the next, known by the Hebrew acronym Pardes, meaning “orchard” or “paradise”:

P: (Peshat, meaning “simple”) This is the most literal interpretation.

R: (Remez, meaning “hint”) This refers to the text’s symbolic meaning.

D: (Derash, meaning “story”) This has to do with digging out the story, perhaps to build a sermon or to teach a moral lesson.

S: (Sud, meaning “secret”) This is the deepest level of understanding. At this level, stories and fables might be studied through the understanding that human action can affect the cosmos; it’s the Butterfly Effect, expressed in metaphysical terms.

More about mystery than mysticism, in recent years the Kabbalah has come to stand for a return to a sense of spiritual wonder and awe. As Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson wrote in the United Synagogue Review, “Ours is an age hungry for meaning, for a sense of belonging, for holiness. In that search, we have returned to the very Kabbalah our predecessors scorned.”

As a Jehovah’s Witness I was spoon fed—no, make that force fed like a foie gras goose—a specific and idiosyncratic interpretation of the Bible. But even at my most devout, I strived to be a truth seeker. As long as I was satisfied with the answers they gave, my journey kept me inside the religion. But, eventually, their repetitive, simplistic answers stopped working. In Judaism I fell among a community of kindred spirits, an entire race of people dedicated to the search for meaning.

So why don’t I scrap this YoS project and convert to Judaism? Simply put, I am not a Jew, ethnically or culturally. The Torah and its traditions belong to the sons of Abraham. I can admire their rituals and I can even walk part of the way with them. No doubt, I would be more than welcome to join their community. But I feel it would be inauthentic to study Hebrew and convert to their religion. The Torah is their story, not mine.

As Rabbi Cahana said, “God has a mission for everyone. It’s different for everyone, and we need to find our own.”

I’d like to imagine that he’s applauding my search, from the center of his synagogue, on the sidelines of my path.

——

*Sometimes their ceaseless questioning takes them down some strange byways. I mean, really, do we need to bicker ad nauseam over whether it’s a violation of the Law to ride in an elevator on a Saturday?

**Confirming my theory that conflict is a form of intimacy.

***I’m reminded of jazz music. Sure, there are plenty of jazz musicians of all ethnicities. But its essence is as an African-American art form; if you want to enjoy it in its purest form, eventually you’ll have to trek to New York or New Orleans and hear jazz from the people who invented it.

****By rejecting, or, at the very least, downplaying, the Jewish voice in Old Testament scripture, Christian theologians have cut themselves off from the flow of history. That rarely leads to good outcomes.

*****Maybe you’ve heard the one about the Jewish mother who traveled to a Buddhist temple in the Far East. Granted an audience with the revered guru, she says just three words: “Sheldon, come home.”