In many ways, there has never been anything like author J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. The books, the films, the characters, and their activist creator have achieved worldwide recognition, and are beloved by hundreds of millions of people. Taken as a series, nothing has ever outsold these books, including Tolkien’s famed “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy. Potter sits happily at the top of the literary heap, and by a wide margin.

But, why? What is so alluring about Rowling’s magical world—so compelling that the fantasy series has become its own, ongoing field of academic literary study, despite the final book having come out in 2007?

To find the answer to this, we have only to look to the concept of Otherness.

The concepts of the Other, and of Othering have been incredibly important parts of literary theory since the 1970s, particularly in the study of identity—branches like feminist theory, queer studies, and postcolonialism, to name a few. To be an Other, quite simply, is to be an outsider—“Woman is the Other of man, animal is the Other of human, stranger is the Other of native, abnormality the Other of norm, deviation the Other of law-abiding, illness the Other of health, insanity the Other of reason, lay public the Other of the expert, foreigner the Other of state subject, enemy the Other of friend,” as famed Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman writes.

To be Othered is to be defined in relation to the group performing the Othering. This process can seem natural, and indeed, is often an intrinsic part of any given culture. Women, for example, have long defined by their differences from men, not the other way around. Notice the phrases “Hit like a man,” and “Fight like a girl” are based upon the male standard of strength, the feminine being the Other—the inferior to the standard.

In Rowling’s world, the Others hold the power. Harry Potter is an orphan, a sad and lonely little boy who is forced to live with people who despise him—with people who define him. The Dursleys, his adoptive family, abuse him, tell him that he is worthless and a troublemaker. Because he isn’t a Dursley, and because he exhibits bouts of uncontrolled and inexplicable magic—he is Othered.

But this doesn’t last long. At the age of eleven, Harry Potter learns that he is a wizard, capable of affecting reality with but a thought and a wand.

He quickly leaves the Dursleys behind, embarking on a coming-of-age journey at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, where he grows from a boy to a wizarding champion.

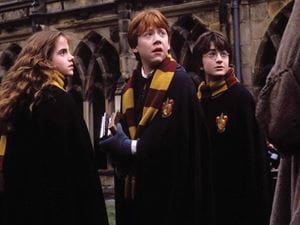

He quickly befriends Hermione Granger, a frizzy-haired bookworm, and Ron, a red-haired boy from a very large and very poor family. Together, they’re an orphan, a girl, and a poor kid—the three Otherteers. Together, these three become the heroes of their world, each playing to their different strengths to conquer every obstacle in their paths, despite numerous setbacks.

So why is this important to readers?

Because we’re all Others to someone, at least to a degree. All of us, regardless of race, gender, or ethnicity. We’ve all been that powerless child or the ostracized friend, or the one that didn’t quite belong.

We see ourselves in Harry, Hermoine, and Ron. It’s incredibly easy to transpose our Otherness onto their own, and to become them, in a manner. This is why franchises like the X-Men perform so incredibly well—they depict a group of misfits finding their place in the world, and finding their power and agency.

This is why Harry Potter does so incredibly well—more than being limited to the three main friends, there are a plethora of characters who have been cast to the sidelines of society, only to find their value, going on to define themselves rather than allowing themselves to be defined. This is incredibly satisfying in fiction.

It’s also incredibly important, not only for our entertainment, but for the betterment of our world. Social institutions—things like the media, the law, education, and religion—can affect the balance of power through their representations of what is “normal,” and what is Other.

So when something like Harry Potter, which sells in the hundreds of millions and has global influence, works its way across the world, it can change ideas in a huge way.

Rowling, in her fiction, reproduces many of the real prejudices we, ourselves may be mired in. For prejudice and discrimination to exist, indifference, ignorance, insecurity, and intolerance must be deeply rooted within a culture or people group. Harry Potter’s tale highlights innumerable instances of this, and shows them to be the irrational injustice that they are.

One of the great strengths of literature is that readers have the opportunity, for the span of a book, to reside within the heads of other people unlike themselves. In the case of Harry Potter, we’re treated to the experience of an orphan, of a woman, of a poor child, and what’s more, to the experiences of creatures seen as sub-human, and of the misunderstood. The moment when we realize that the distinction between a “pureblood” wizard and a “mudblood” is absolutely meaningless, we also realize such distinctions are meaningless in the real world.

Of course, many other books allow us these same experiences, but the simplicity of Harry Potter, the universality of its tale of growing up and learning who and what you truly are—these things have propelled the series to immense fame.

Rowling has not wasted this fame, this powerful platform. She writes that “You have a moral responsibility when you’ve been given far more than you need, to do wise things with it and give intelligently.” And indeed, she has continued to engage in the very issues Harry deals with—discrimination, prejudice, and a lack of dialogue. She works with orphans worldwide through her organization, Lumos, which is focused on ending the institutionalization of parentless children. She also continues to advocate for oppressed groups everywhere, using the weight of her name to raise awareness concerning discrimination. For Rowling, the end of Harry Potter’s tale was not the end of her good works.

It is no coincidence that what saves Harry, as a child, is not strength. It is not a bolt of lightning, nor the violence of the sword. It is love. His mother’s sacrificial love proves more than a match for the deadliest spell in existence, performed by the strongest wizard. In this, we see the power of unity revealed, the power of turning them into we.

If we can only learn this spell, ourselves, the world will be a better place for it.