Many of post-punk’s leading lights, in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, found a music-video home in a loose version of minimalism that sought to embrace its simplicity of task. Videos looked to minimalism to return some self-respect to an art form sapped by the booze-and-babes ethos of metal bands. Looking to film history (always a potent source of material for the music video), videomakers embraced the long take (uninterrupted shot) as a mark of high seriousness, and as a touchstone of realism. Realism, a principle heretofore mostly absent from the spectacle-craving music video, meant stripping away the unnecessary, and returning dignity to the musician’s labor.

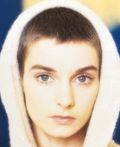

The movement toward the unadorned took a slightly different tack with Sinead O'Connor's "Nothing Compares 2 U" (1990), directed by John Maybury (click here to watch the video). The video sought to cut away everything, with the exception of her face, focusing almost exclusively on O'Connor's visage. "Nothing Compares" opens with brief glimpses of a rural road before a lap-dissolve (a film process involving superimposing two scenes, so that, for a few moments, they are seen simultaneously) reveals a close-up of O'Connor.

With her striking, rough-hewn features, buzz-cut hair, and pale skin, O'Connor met no traditional standard of feminine beauty, but some combination of her skill as an actress and the sheer force of her personality, clear even here, made it difficult to look away. Maybury makes more of O'Connor's peculiar power by making less of the video's surroundings; and in fact, there is little grounding to "Nothing Compares 2 U."

The world outside O'Connor's face is only a shadow here, with each of the shots of stone walks, statues, bridges, and lonely men gazing off into the distance clearly marked as products of her own memory. Small changes loom large in "Nothing Compares 2 U"; O'Connor begins the video in a close-up shot, avoiding the camera's searing gaze when singing, and only looking up when silent. As her singing grows more forceful, she grows more willing to look directly into the camera while singing, before returning to averting her gaze.

O'Connor's shaved head and intense manner cannot help but bring to mind one of the great icons of the silent cinema, Maria Falconetti in Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc.

O'Connor was a singer-icon, like Falconetti, an emblem of suffering and Christian forbearance. That Sinead is mourning the loss of romantic love, rather than matters spiritual, becomes irrelevant, lost in the passion of the sole tear that runs down her cheek. The statues that serve as a recurrent motif in "Nothing Compares 2 U" made much the same point, comparing O'Connor to icons of passion, sadness, and endurance, with the woman holding her brow in her hand being perhaps the most explicit. The tear, though, is essential to the nature of the minimalist ethos. In a less austere video, the single tear would be little more than a cliché, a sappy convention of deeply felt emotion.

It is the long takes of "Nothing Compares 2 U" that render the emotion a matter of spiritual significance. The long take gives "Nothing Compares" a sense of duration, of one event organically following the next. As spectators, we see the song sung, and the emotion that wells up, and they emerge from the same shot, out of the same milieu. There is no cut-separation, nothing from the toolkit of the FX-savvy filmmaker to establish distance from the action. The minimalist video reaches for a truth it finds in the emotion of one song, one event, one face. An artier, higher-gloss minimalism was on display in R.E.M.’s clip for “Losing My Religion” (1991). “Losing My Religion” is the epitome of postpunk’s movement from poverty to aesthetic splendor, from crude low-budget efforts to polished, tasteful videos (click here to watch the video). R.E.M. themselves are representative of the shift, having gone from low-budget, rapidly assembled works to the MTV-friendlier “Losing My Religion.”

An artier, higher-gloss minimalism was on display in R.E.M.’s clip for “Losing My Religion” (1991). “Losing My Religion” is the epitome of postpunk’s movement from poverty to aesthetic splendor, from crude low-budget efforts to polished, tasteful videos (click here to watch the video). R.E.M. themselves are representative of the shift, having gone from low-budget, rapidly assembled works to the MTV-friendlier “Losing My Religion.”

Lit and shot to resemble an Italian Renaissance painting, or some admixture of Andrei Tarkovsky and Michelangelo Antonioni, “Losing My Religion” (directed by Tarsem) wanders through time and space, watching angels and angel-manqués suffering under the gaze of the unbeliever. A teenage St. Sebastian poses, pierced by arrows in an erotically charged tableau; a father mourns his dying son; Eastern Bloc workers pound at a piece of steel; and interrogators poke around an old man’s chest, sticking their fingers under a wing-like protrusion on his breast. The mournful tone of the stream of images, each as carefully composed and lit as a painting, was a reminder of Tony Kushner’s famous statement, from his play Angels in America, that “there are no angels in

Meanwhile, the band wanders across an empty room, a jug of milk smashes on the ground, and Stipe does a flailing solo dance. Everyone in the video, from Stipe on downward, poses with angels’ wings, and the video’s tableaux of beautiful freaks clothed in gloriously colorful costumes gathers force with each repetition, each intonation. Tarsem’s skilled craftsmanship made him a new kind of minimalist director—one who did not believe in the catch-as-catch can visual aesthetic of earlier, lower-budget videos for alternative-rock acts. “Losing My Religion” endorses the minimalist ethos in its all-in-oneness. The video was a unified object, leaving meaning to be sorted out by others. “Losing My Religion” is like an early-90’s update of a certain brand of 1960’s art-house film, meant to be seen repeatedly, and argued over. Its fundamental purpose is to be beautifully gnomic.

Like “Nothing Compares 2 U,” “Losing My Religion” found a spiritual component in image-making, offering up moments for contemplation, silent patches amidst the throbbing din of the music video. Paths (mostly) not taken, these two iconic clips offer a glimpse of a music video that might have been—slow, dreamy, and striving for the sacred.