A multi-religious dinner table always presents a bit of a problem when it is time to say the grace before meals. But Thanksgiving presents a particularly sticky situation, because it is the one occasion on which even the irreligious feel that some sort of invocation should be made. But who, or what, should we invoke?

After several minutes of communal hemming and hawing, one of the braver of our number delivered a prayer to the earth, thanking it for its bounty and seeking its forgiveness for our environmental sins. In all, it sounded more Green Party than pagan. Having crossed that hastily improvised bridge, we tucked into our feast.

But the moment stayed with me, for it illustrated what a peculiar, not to mention sneaky, holiday we were celebrating.

Thanksgiving is not a purely civic holiday like Memorial Day or Independence Day, although we are, in part, celebrating the fortitude of our Pilgrim forebears. Nor, like Christmas or Passover, does it come freighted with the content of a particular faith. Rather, Thanksgiving straddles these two categories; it is civic and religious. To paraphrase Jesus, Thanksgiving gives both to Caesar and to God.

In doing so, it discomfits believer and unbeliever equally. For giving thanks assumes the existence of one (One?) who deserves our gratitude--anathema to atheists. But giving thanks as a nation assumes that we stand before God as citizens of a country, as well as members of a faith. And that should offend anyone who believes that salvation flows from the church and not from the state.

Thanksgiving, in other words, assumes the existence of something that doesn't exist: an American faith.

On these grounds, I suppose one could argue that this holiday violates the establishment clause of the Constitution. I leave that task for some particularly dogmatic member of Americans for the Separation of Church and State. What interests me is the ubiquity of gratitude, the understanding, even among witnessing atheists, that it is important to be grateful for our good fortune.

You can take that argument or leave it. But if you leave it, help me to understand why we experience this particular species of gratitude. I'm not talking about the kind of gratitude we feel toward someone who has done us a favor. I mean the sort of global gratitude inspired by gifts we could not have known enough to ask for, or the kind we feel when matters beyond our control end well for us.

Who do you thank for your sweetheart's brown eyes; for growing up where it snows (or doesn't); for being alive at the same time as Bruce Springsteen; or for seeing your children born into a country that is prosperous and at peace?

You might argue that there is no one to be thanked. Maybe all our purported blessings are a matter of random chance. Perhaps the desire to extend gratitude beyond the human is an evolutionary glitch--a useful social trait that got too big for its britches.

Perhaps.

Or perhaps we awaken one day and realize that we are not now, nor have never been, masters of our own destinies; that our successes were not entirely of our own making; that our souls magnify the Lord, whether we like it or not.

Again, you can take this argument or leave it. It is easier to believe in chance than in grace. Chance requires nothing from us. In fact, if life is a succession of random events, than any response to good fortune is superfluous.

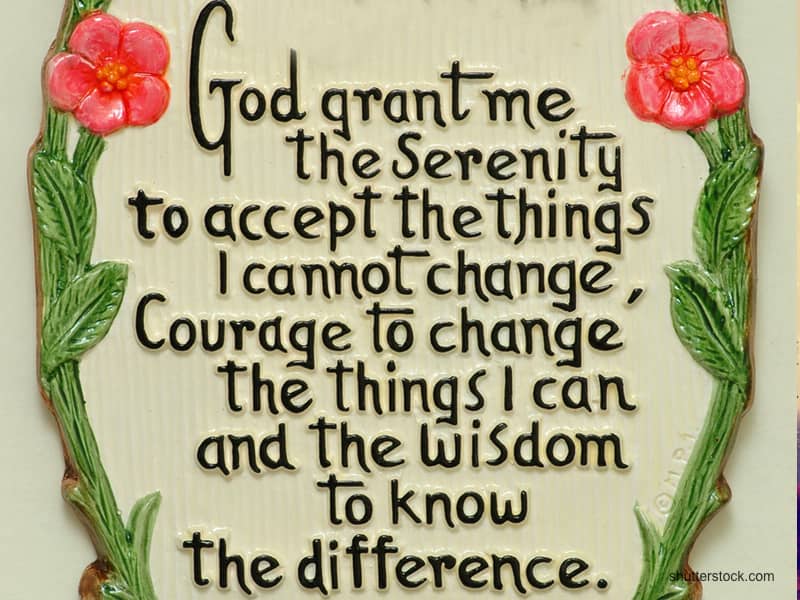

Grace is different. In receiving grace, we are challenged to become channels of grace. This is more than a matter of a few good deeds (although those help); it is an invitation to place one's self in God's hands, and devote one's self toward what we perceive as God's ends.

Thanksgiving, then, is a call to action: a gentle poke to awaken our collective conscience from its postprandial slumber. To whom much is given, etc. etc.

In a county as religiously diverse as ours, we may never be able to express our gratitude in words that are acceptable to everyone. Fortunately, deeds work even better.